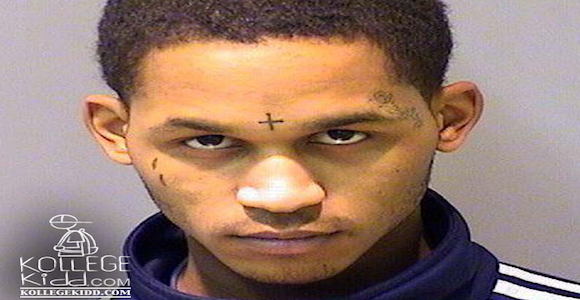

The Origins of Forehead Cross Tattoos? March 8, 2018

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackbackThe Forehead Cross

The forehead cross has become a relatively common modern tattoo, both in the industrialized west and among some developing countries. However, those who wear it will probably not know that the first record of this design dates back to the sixth century AD. Let us travel through time and space to the borders between two of the three Euroasian superpowers: Rome and Persia (the third being, of course, China) and await the arrival of the tattooed warriors from the north…

Prisoners

In the late 580s the Persians and Romans did something very unusual. Rather than fight one another they united in a campaign against a Persian usurper Bahram. In 588 or 589 the Romans’ Persian allies won a famous victory over Bahram. In gratitude for Roman help the Persian monarch, Chosroes II sent a number of Turkish prisoners from among the captured enemies. At this date the Turks had nothing to do with ‘Turkey’. They were Steppe flotsam: nomadic warriors who had been hired as mercenaries to wreak carnage on which ever enemy was paying less.

The very fact that the Turks were sent to Constantinople suggests that the Persian king considered the Turks to be exotic: though both the Roman and Persian armies had already fought the Turks with what we might politely call ‘mixed success’. However, what really fascinated the Roman Emperor Maurice when he met them (WIBT) were the crosses…

On their foreheads was inscribed the sign of the Lord’s passion, which is called a cross by the ministers of the Christian religion.

Plague

We do have some passing evidence that eastern Mediterranean Christians tattooed themselves with Christian symbols in late antiquity. It is likely that Maurice was surprised not by the tattoos per se, then, but by the fact that a cross appeared prominently on the body of a people that were not at this date particularly associated with Christianity.

So the emperor enquired what was the meaning of this mark on the barbarians. And they declared that they had been assigned this by their mothers: for when a fierce plague spread among the eastern Scythians, it was fated that some Christians advised that the foreheads of the young be tattooed with this sign. The barbarians in no way rejected the advice, and they obtained salvation from the counsel.

It is nice to speculate what really happened here. Christian missionaries (or even just Christian merchants) worked on the Steppes and took advantage of a plague to stamp their spiritual authority on the Turks: this ought not to come as a surprise. But should we imagine: (i) that noticing that the Turks had many tattoos, the missionaries asked for a Christian tattoo; or (ii) was it that the Turks saw the missionaries signing the cross on foreheads and reasoned that it would be better to do this permanently with ink rather than temporarily with air or water or ash? Or are there other possibilities: drbeachcombing AT gmail DOT com

Source

Theophylactus Simocatta’s History (V, 10): the text was written a generation after these events recorded here. Note that there is uncertainty about the dates, which some authorities push up to 591. For present purposes this is unimportant and Beach has a long day ahead of him…

Responses

Doug, 9 Mar 2018: ‘there was also the early Byzantine practice of ‘Christianising’ statues of Roman worthies by carving (often rather crudely) a cross on their foreheads. There’s some quite nice examples in the Selcuk museum in Turkey, and doubtless elsewhere.’

Bruce T, 9 Mar 2018: ‘The Nestorians were in the Turpan Depression and the Sogdian region proselytizing shortly after becoming the official Persian Christian Church in the mid-late 6th cen., with a translation of the Bible into the Turkic script in the Turpan, purported to be from the late 6th cen. (A dispute on that one.) and in China proper in decent numbers in the early Tang in the early-mid 7th cen. So they were definitely out there trying to convert the Tengristic(?) believers, who owned the steppes at this time, the Turks being one of many nomadic groups from Bulgaria to nearly Korea who shared this religious system of the horse pastoralist. The epidemic story is a nice one that fits the belief system of the Christian West, but is it true? The cross is an old sun symbol, Tengrii was the God of the Great Blue Sky. Evidence of tattooing as shown by various ‘ice mummies’ on the steppes in the 2nd millennium B.C.E. Two, Buddhists of various stripes had been proselytizing the same regions for a millennium before the Christians got out there, many with magico/religious and medical tattooing traditions either homegrown or assimilated in their travels and work. The cross is also a Buddhist sun symbol. (I had a number of Thai friends with cross tattoo’s they’d picked up in their stint as boy monks. Not between the eyes, though.) I do find it interesting that the Imperial Church of The West was trying to take credit for the work of the Nestorians they ran out over the Arian controversy nearly a century before. If they’ll lie about that, what else will they tell whoppers about? One thing in the favor of their tale, DNA evidence in the past couple of years shows the Plague of Justinian was the bubonic plague. The prime plague reservoir in Eurasia is the marmots of the steppes which are still eaten regularly by the people there. The secondary is black rats of the Gangetic Plain. Wet years cause surges in burrowing animal populations on the steppe and human populations expanding with the grass and their flocks. The ‘invasions’ of the Huns, Alans, Bulgars, etc.. were all part of a near two century period of wet warm weather on the steppe and the need for expansion for grazing. The mid-6th cen. was the end of this period and when Justinian’s Plague hit the West. Scared groups on the steppe devastated by the epidemic may have turned to the Nestorian ‘cure’ as a last ditch ‘any port in a storm’ effort to stave off the pestilence and adopted the forehead tattoo as a remembrance of who had bailed them out, i.e. the Nestorians. However, shipping via Basra on the Persian Gulf and the head of the Red Sea to and from the ports of India was also in full swing in this period. Rats or marmots, pick your poison on the plague vector. I’m a marmot man on this one. In other words, who knows where or why the Turks came up with notion of crosses between the eyes? They had their own reasons for them and as it was a holy symbol in the West, we’re only seeing the interpretation from their side. It could have meant something as simple as ‘He’s married, he’s mine, hands off.’ from the wife of an elite Turkish warrior to the other women in the region. Semi-off topic, why do I suspect these crossed Turks had an influence on the ‘Prester John’ nonsense of a few centuries later?’