Baby Face Günter in Saverne January 8, 2018

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackA delicate occupied zone with an unfriendly population. Think US Marines patrolling in southern Afghanistan or Israeli troops walking through a Palestinian village. That is challenging enough. But could we make it a little more interesting for, say, an HBO series? Why not, for example, put the occupying troops under the control of a young man with a fiery temper, poor judgment and little experience. Let’s make him twenty and to drive home the point let’s give him a baby face. Better still have Baby Face tell his soldiers to shoot representatives of the local population.

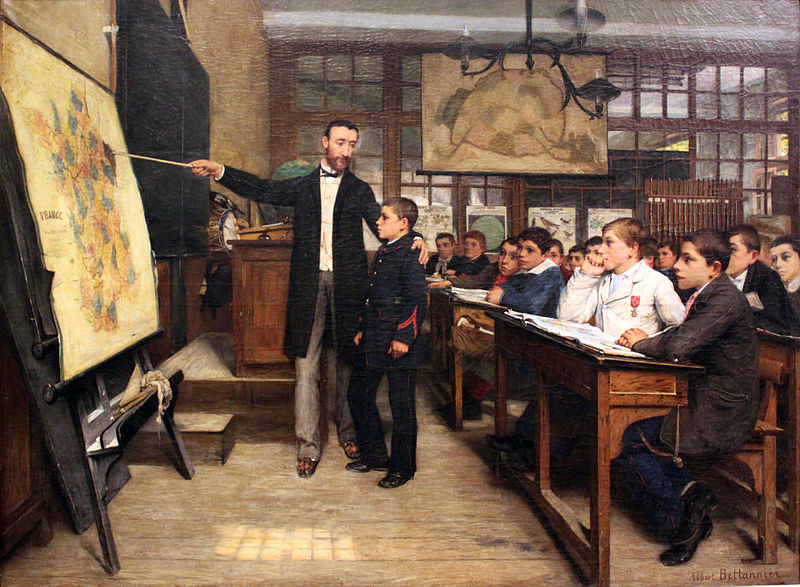

These words are not, of course, fantasy, but describe the events in 1913 in Alsace, one of the French provinces annexed by Germany in 1871. Forty years had gone by, but the French-speaking population continued to view the Germans with great suspicion. The German military that occupied the area returned the compliment and soldiers routinely referred to Alsatians as Wackes, ‘wasters’. Then, across the border, the French eyed their lost provinces and planned revanche (see the black marks on the map in the illustration). It was into this very dry tinderbox that the German army posted a young officer with a pleasant-smile, Lieutenant Günter Freiherr von Forstner, ‘a hero and a chocolate eater’.

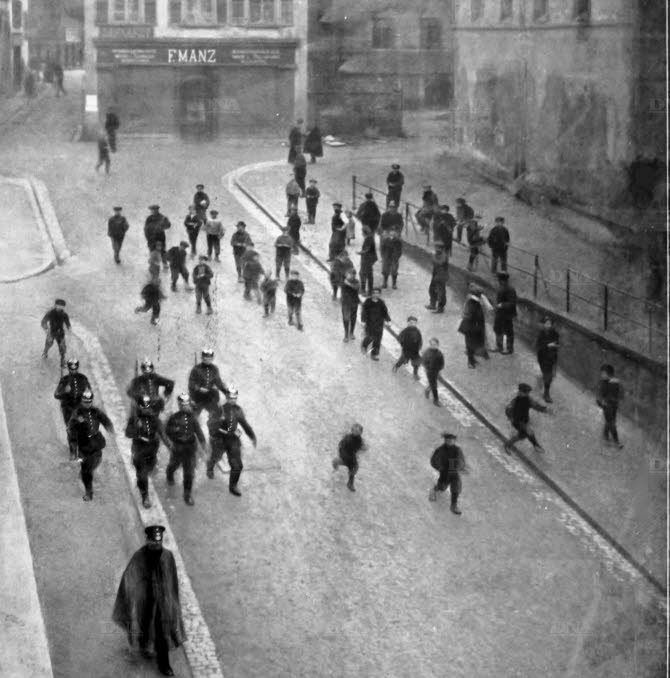

Günter was one of, forgive us, those idiots who sometimes shunt world history along. His fifteen minutes of fame began when introducing some new troops to the area that he would have called Zabern (French, Saverne). The lieutenant told them, 28 Oct 1913, that he would be impressed if they shot some Wackes. He also invited German soldiers to defecate on the French flag. When news of this was published in the local newspaper feelings were inflamed. There were four days of protests and the townsfolk sang, mein Gott, the Marseillaise! The locals also gathered outside the barracks and took to following Günter around: the young man was given his own escort (see photo, the moment this blogger would have given a great deal to witness in person, look at the children). 2 December, about a month after Günter’s inflammatory comments, a cobbler laughed at the sight of Günter marching. Günter, naturally, took out his sabre and beat the man half to death: paralyzing him on his left side.

That the German army had a young officer who lost his head can hardly be a matter for surprise: many similar cases can be catalogued from other European countries and particularly from their Empires. Ideally you don’t put immature men in charge of warriors with weapons, but in a country with a rigid social order needs must. However, what is truly remarkable about this case is the way that the German army reacted. Surely, common sense dictated that Günter be immediately transferred or, were he to stay, that he be given some kind of slap on his wrist if only for an easy life with the local French population. But the German army, while its commanders were horrified by what their little enfant terrible had been getting up to, were much more concerned with the honour of the armed forces. They could not, then, allow themselves to be seen to react against one of their own, in the name of Wackes, social democrats and socialists.

The army dug in. Günter was given six days house arrest after his initial comments: though this was not publicized. So, yes, there was a slap on the wrist, but it was done in private, while no one was looking. Ten soldiers, on the other hand, were arrested for giving information to the press. After attacking an unarmed man with a sword Günter was publicly given forty-three days arrest, but this was cancelled on appeal: Günter had, apparently, been defending the honour of the German army when he lay about the cobbler. The events of November and December 1913 became part of a national debate on the role of the army in German life and there can be no question that the German army and its supporters won, both in the Reichstag and in Alsace.

The scene was set for the German army’s take-over of civil government in the Great War: a fate that Britain and France happily avoided. One other striking effect was the toughening up of occupation laws in Alsace. By 1915, admittedly in changed circumstances, it became illegal to speak French in a public place: saying bonjour to the butcher could get you a fine. And in that very same year poor old Günter gave his life for Germany in Belarus fighting against the Russian army. Did he get some last salvos off about shooting local ‘Ruskies’ or using the Russian imperial flag for toilet paper. Beach does not doubt it for a moment.

More on Günter: drbeachcombing AT gmail DOT com Beach would love to learn more about his life before or after Nov and Dec 1913.