Review: Hitler’s Forgotten Children December 5, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback

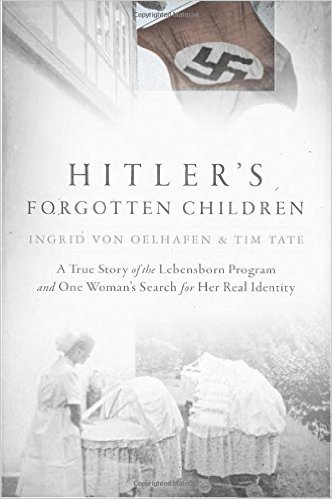

Lebensborn is a Nazi word to place side by side with such Teutonic charmers as Einsatzgruppen, Lebensraum and Endlösung. The Lebensborn or Life’s Fount was a scheme to breed a hundred million blond supermen and their hand maidens. It had various reflexes: sex between consenting Aryans was encouraged, against conventional Christian morality; Aryan women siring children out of wedlock were cared for; and ‘Aryan’ children who happened to be found in the vast territories to the east were seized from their families and reassigned to German parents. In some cases before slaughtering villages German race specialists would remove any very young kids who happened to have the right skull and face measurements. Ingrid Von Oelhafen’s Hitler’s Forgotten Children: My Life Inside the Lebensborn is not the best history of this particularly twisted strand of the thousand year Reich. But it is valuable for showing what the process did to the children involved, while excavating, at the same time, a couple of hidden coal faces of the human condition. Ingrid was herself taken from a Slovenian village as a baby and reassigned to some painfully screwed up versions of ‘the master race’ in eastern Germany. She had few clues about her real identity until her later middle age, when she was informed that she was a Lebensborn child by a German professor.

The book communicates an honest, a loving and a valuable person – Ingrid works with disabled children – who has though never really felt at home in her own body. You should not buy Hitler’s Children because you want to know the history of Lebensborn: there are better places, even in English, to look for that. You should buy this book because of Ingrid and Ingrid’s story, as she travels to the region of the Balkans from which she was stolen and relentlessly tracks down her family: who do not believe that she can be who she says she is…

Beach’s strongest impression reading the book was not Ingrid’s personality, but the absurd nature of identity. How fragile, labile and foolish is our sense of belonging! At one point when researching Yugoslavia Ingrid reads about the partisans there and feels a glow of pride for a country that she has never visited (though where she’d happened to be born) and about which she knows nothing. She criticizes Germany, particularly Nazi Germany and, yet, she gives the impression of someone who has the great German virtues to hand.

The central scene in the book comes when Ingrid decided to confront a family member – some spoilers suppressed here – who does not want to meet her. Ingrid arrives under her biological sister’s house, prepares to ring the bell, then realizes that the old woman living a few feet from her is just as much a victim as she is. She walks away without making that final contact: and the reader and the author share a moment of blinding clarity. This is life affirming stuff, but not in that self indulgent art house cinema way, where an eagle flies above a last scene. Quiet acts, quiet lives, quiet people… To be recommended.

Other interesting books: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

Note that this book was spotted in the New Books category. No review copy was given though, damn them!