The Cuckold, the Painted Belly and the Lusty Merchant November 25, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

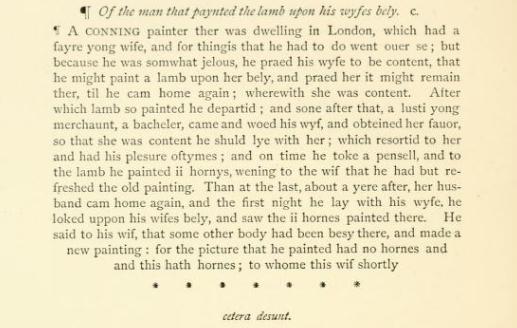

This is a weird sixteenth-century story/anecdote/joke about marital infidelity. It is also, frustratingly, only 95% complete. The punch line is missing. Beach has ‘translated’ the text into modern English. The original text though is in the screen capture below. Please email any serious mistakes.

A cunning painter was living in London, and he had a fair young wife, but he had to go over sea. However, as he was somewhat jealous he asked his wife whether he might paint a lamb upon his wife’s belly, and he prayed her that it should remain there until he came home again and she agreed to this.

It is not exactly a chastity belt, is it? Not sure what the lamb was supposed to mean. In any case, the second movement involves a lusty merchant from down the road.

After the artist had painted the lamb he left and soon after a lusty young merchant, a bachelor, came and wooed the painter’s wife and ‘obtained her favour’, so that she was content he would lie with her and he visited her and often had pleasure. Then, one time, he took a pencil and drew two horns on the lamb, claiming to the wife that he had only ‘refreshed’ the painting.

Horns are the symbol of being cuckolded in much of Europe: the origin of our two fingers over the head of people we pose in pictures with. There next comes the husband’s return.

About a year after the husband had left the husband came home and the first night he lay with his wife. Then he saw the lamb with the two horns painted there. He said to his wife that someone else had been busy there, and had made a new painting; for the picture that he had painted had had no horns and this lamb had horns. His wife shortly…

And here the story ends: the editor signals this with the Latin ‘cetera desunt’. It is very frustrating. The tale is near a climax. If this tale follows the pattern of most English humorous stories from this period the wife probably found a way to get out of trouble with a witty riposte. Beach has failed to think up what it might have been. Perhaps someone can help: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

Source: W. C. Hazlitt, A Hundred Merry Tales: The Earliest English Jest Book (1888), 16

Chris S writes, 25 Nov 2016 (as did Kevin M – thanks), in: Transcribed from Tudor Tales by Dave Tonge, The History Press and it is available as an ebook from Amazon. There was once a clever painter from Breton who was a master of his craft and a man of older years whose daubs were famed for the look of the real world that he captured on his canvases. His portraits too bore a wondrous resemblance to all those who sat before is easel and those he painted were portrayed full of life, their eyes bright, their complexions lusty. Such was his skill that the painter was in great demand, whether it be painting a likeness of some ambitious alderman, or perhaps a hunting scene on a rich merchant’s parlour wall. At other times he could be found illuminating a manuscript, a bible perhaps or other moral work for a mayor or a nobleman’s wife. And sometimes he even contrived a miniature of some well-born lady to be kept close to a lovelorn lad’s lonely heart.

Such was the master painter’s skill that he was often called away to work his artistry in other towns and even far-off countries. He had as a younger man enjoyed the travel, sampling the delights to be found in far-flung places and enjoying himself all the more because he was working in towns where most did not know his name, nor could they tell his family and friends of his misdeeds, being so far, far away from home. But he was no longer a young man, travel no longer found favour with him, not least because he was at an age when over-exertion caused him to ache from the insides out. That was reason enough, you might think, to keep to hearth and home, but he had another cause more pressing still to travel no further than his studio set high in an attic room of his house, for the painter had recently taken a young wife who was comely to behold.

Like many of the young women you will hear tell of in this my book, she was beautiful. Suffice to say that she was prettier still than the pear tree in full blossom and the soft, sweet flesh of that particular fruit was no more sweet and soft than the flesh that covered her slim and wanton frame. Well, the painter had an artist’s eye, he could appreciate beauty, but as a man who studied the detail in all things, he also had an eye for ugliness and all manner of evil behaviour. He saw it everywhere and having practised it himself long ago, he knew it well enough. How then could he continue at his trade, journeying wherever his skill with a brush was needed? How could he leave his wife alone to be admired by those who were not guided by their appreciation for beauty, but only by their base desires? He feared he could not, lest he find a way to protect the work of art that was his wife.

The answer was for his young wife to become his canvas, that she should herself take the place of the wood panels on which he so often practised his art. And so it was he lay his wife upon the bed and there did use all the cunning of his craft to paint a lamb upon the lower part of the young woman’s belly. It was a rendering so finely wrought that none could lie with his wife lest both the image and his wife be defiled. It was an image so lifelike that if it was spoilt, then none could repair the damage nor replicate the lamb that he had crafted just below his wife’s navel.

Satisfied that by painting alone he had protected his wife from the attentions of lewd and unseemly men, the master painter packed his brushes and boards and left upon his business. He left his wife to take charge of his household, his servants to care for his wife and a young journeyman painter new to his service to see to any small painting jobs that needed completing while he was away at his trade. But t he young journeyman painter was not that willing to see to the commissions yet completed by his master and was far more interested in seeing to his master’s young wife instead!

At first the painter’s wife would not consent to his pleas, not least because she feared her husband’s artwork would suffer from the young man’s attentions even if she did not. But she was as young as the journeyman and she too had needs and desires that her husband had trouble fulfilling when he was there and now he was not, well what could she do? For as everyone knew long ago, such unsatisfied young women’s wombs were want to wander. It is hardly surprising, then, that eventually she relented to the young man’s demands. At last he obtained her favour, at least six times before the Whitsun last past and diverse times thereafter!

With such attention to detail the painting of the lamb suffered greatly and soon the master painter would be returning home after two full years away. Their lusts sated, both the journeyman and his master’s wife’s thoughts turned to preserving their livings. And so it was that the journeyman painted a ram complete with long curling horns where once the lamb had lain upon the young woman’s belly. And just in time, for the master painter came again to his house and went straightaway to see his young wife.

He used her roughly and demanded to see the lamb he had painted below her navel. ‘Show me the painting,’ said he, ‘and then we shall have some fun.’ Obediently his wife undressed and her husband looked at her belly. Seeing there a great horned ram he grew angry. ‘What’s this?’ he cried, ‘I painted a lamb, but now I find a ram!’ His wife, having guile and cunning enough to put the trickster Howleglas to shame, replied, ‘Why, husband, did you not know that a lamb so cunningly painted would grow into a ram in two years? If you had been a loyal husband and come home sooner, then you would have found a lamb still!’

And there the tale of he who painted a lamb ends. We must assume that the great skill the master painter displayed with his brushes was not matched by the wit and the workings of his head. For once again, a man’s art was no equal for a woman’s artful nature.

Did this artist not think his wife would be taken doggy-style and preserve the lamb?

Invisible writes, 25 Nov 2016: To the best of my recollection the story appears in Libro del buen amor, where the painter is called Pitas Payas, of Brittany. The clever wife tells her husband that the lamb has grown during his absence. (Surely the word “grown” hints that she is pregnant by the lover.)

David O, 25 Nov 2016, writes in with a relevant link for Invisible’s Libro. ‘The one with the duck is funnier.’ writes David…