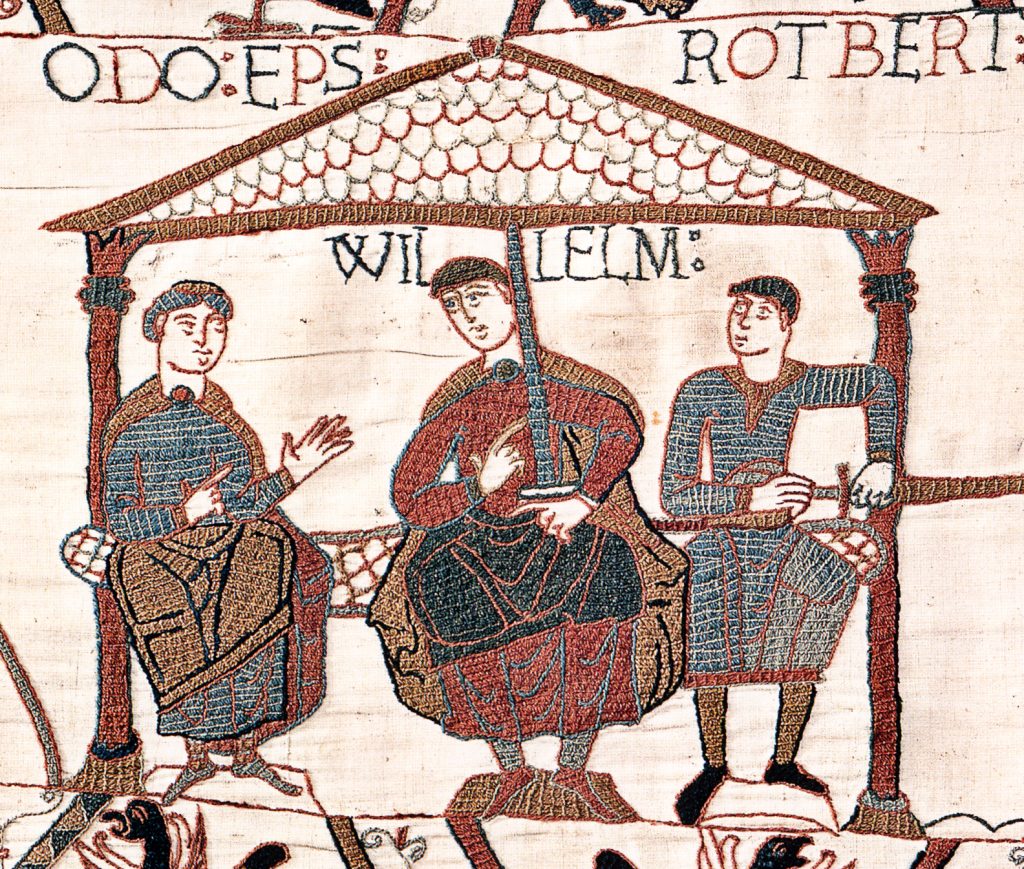

Did William the Conqueror Fall? July 8, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackback

One of the stories handed down to generations of British school-children is the idea that William the Conqueror, on arriving in England, slipped as he was coming ashore. This, of course, was a terrible omen (for the Anglo-Saxons).

In his eagerness to get to the shore, as he leaped from the boat, his foot slipped, and he fell. The officers and men around him would have considered this an evil omen; but he had presence of mind enough to extend his arms and grasp the ground, pretending that his prostration was designed, and saying at the same time, ‘Thus I seize this land; from this moment it is mine.’ As he arose, one of his officers ran to a neighboring hut which stood near by upon the shore, and breaking off a little of the thatch, carried it to William, and putting it into his hand, said that thus he gave him seizin of his new possessions. This was a customary form, in those times, of putting a new owner into possession of lands which he had purchased or acquired in any other way. The new proprietor would repair to the ground, where the party, whose province it was to deliver the property, would detach something from it, such as a piece of turf from a bank, or a little of the thatch from a cottage, and offering it to him, would say, ‘Thus I deliver thee seizin’ that is, possession, ‘of this land.’ This ceremony was necessary to complete the conveyance of the estate (175).

This is from a nineteenth-century bio-pic, Jacob Abbott, History of William the Conqueror, a nauseating book which is, in great part, fictionalized. Did Abbott make the tale up then, or does this has some kind of basis in eleventh century sources? Well, eleventh-century, but the story does appear in thirteenth-century sources, namely Roger of Wendover’s Flores Historiarum (the Flowers of Histories).

In quitting his vessel, duke William slipped and fell; on which, a knight, who stood near, gave a happy turn to the accident by saying, Duke, you have taken possession of England as its future sovereign

‘Dux uero Willelmus in egressu nauis pede lapsus, casum in melius commutavit miles qui prope stabat, dicens, ‘Dux,’ inquit, ‘Angliam tenes, rex futurus’.

Note that there is also a more elaborate Latin text, whose origins Beach has been unable to track down but which is clearly dependent on the briefer passage: Dux uero Gulihelmus in egressu nauis, pede lapsus, illud in omen malum et sinistrum euentum pallens est intepretatus. Sed quidam de militibus, collateralibus, qui Ducem a casu erexit, adhuc limum in manu tenentem, casum in meliorem interpretationem commutauit dicens: Dux felicissime Angliam iam tenes subaratus. Ecce terra in manu tua est accingere erectus in spem bonam, rex future.

Two points, here. First, Abbott has elaborated the story out of all recognition. Memories of attempts to ‘improve’ Chaucer in the same century. Second, this is a relatively late text, written sometime before 1235. It is conceivable that a memory has been handed down, but it could just be a put up job by the Norman dynasty. That it may be a borrowed account is hinted at by an episode from ancient history. Suetonius claims that Caesar fell from the boats while disembarking in Africa:

Prolapsus etiam in egressu nauis verso ad melius omine: ‘Teneo te,’ inquit, ‘Africa.’

Even when he had a fall as he disembarked, he gave the omen a favourable turn by crying: ‘I hold thee fast, Africa.’

Of course, it could have happened to both, but this sounds suspiciously like a transferred story and in terms of personality, we seem to be closer to Caesar than William.

Other thoughts: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com