Review: The New Civilisation? October 5, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackPaul Flewers, The New Civilisation? Understanding Stalin’s Soviet Union, 1929-1941 (2008)

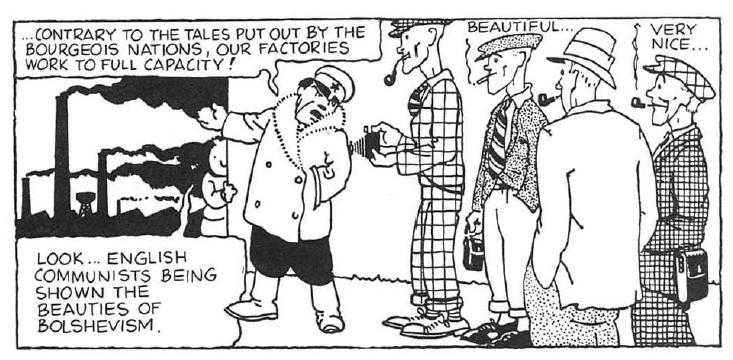

There is a strip in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1930), where the intrepid boy reporter spies out some British leftists who are visiting ‘the new civilization’: the Soviet Union about five years after Stalin had ascended the blood steps to the iron throne. Walloon Tintin, enjoys a laugh at the expense of Stalin’s useful idiots, the pipe-smoking, plaid-wearing Brits: he then, if memory serves, goes to the Congo to kill wild animals and defend Belgium’s ghastly colonial project in central Africa. Tintin is a nice reminder that no one emerges from history with clean hands. The well-meaning quiffed one became an agent of one of the nastier brands of European imperialism and a Catholicism that verged on the anti-semitic; while several thousand well-meaning British and American intellectuals bowed their knee in the court of the Red Tsar.

Paul Flewers in his The New Civilisation takes these visiting ‘Soviet’ intellectuals as his subject: ‘Idealists from a dozen exploited nations, freaks and cranks of a dozen creeds… some bearded lads in red shirts and green suspenders, proud that they were not like other men… thin virgins seeking a new religion [love this], schoolteachers flirting breathlessly with heresy, and professors anxious to approve of everything (Will Durant).’ Why did men and women who, under normal circumstances, led decent lives, making honest attempts to be good citizens and neighbours at home, fall for the ghastly imbroglio of a state that was busy murdering millions of its own? Tintin’s creator Hergé was simply following the traditions handed down to him: traditions he had largely liberated himself from by the late 1930s. These sons and daughters of liberal democracies had no such excuse.

PF does not inconvenience the reader with a master theory as to why so many made the journey to Stalin’s state or supported it at home. But Alfred Sherman is quoted to the effect that ‘It was not so much that [that fellow travellers] were deceived by Soviet propaganda as that they deceived themselves with the aid of Soviet propaganda’. To which might be added George Orwell’s observation that Britons only became truly interested in Soviet civilization in the 1930s, once it had become self-evidently totalitarian. There is something taboo-breaking in the intellectual’s journey to Moscow: in Freudian terms (echoes of Arthur Koestler), the decision to break ‘false consciousness’ belonged to the id not to the superego. That those undertaking the journey and writing ecstatically about their experiences seemed not to be in the least aware of these atavistic needs just adds to the general tragedy.

PF is perhaps the perfect guide for this voyage into the 1930s, because while not, in any proper sense, a fellow Soviet traveller, he is clearly of the left. This means that he is, as historians should always attempt to be, sympathetic to the needs and prejudices of his subjects, individuals with whom he shares values, if not their Soviet conclusions. Sometimes he can descend a little too far into ‘dialectics’ for an interested outsider: and sometimes he drives onto the technical hard shoulder for a mile or two. But if Robert Conquest would have written a pacier book, PF has written a more useful one, because Conquest would never have had the patience to follow the logic of the 1930s left through to its ‘terminal buffers’. PF writes, in any case, for the most part, smoothly and with wit: one section for instance has the lovely title ‘Trial and Terror’!

The book stands as an excellent introduction to one of the most depressing features of contemporary life: the vulnerability of our intellectuals to ghastly ideologies.Widely-read nineteenth-century thinkers seemed largely inoculated against these dangers: at worst they played around with fringe Christian issues (think Tolstoy or Ruskin). But one of the features of twentieth and twenty-first century intellectual life is the way that the supposed application of reason has allowed ‘public thinkers’ to defend, again and again, the indefensible. In the 1930s it was the Soviet Union, today it is the western Islamist left excusing ISIS or worse still western ‘liberals’ wanting ‘dialogue’ with the Caliphate: dialogue that is with jihadists who crucify homosexuals and shop in slave markets. In this way the present leader of the British Labour Party, for example, has become a useful idiot (that phrase again) for murderers and sadists who despise him. Western democracy looked a lot shinier after the Second World War had brought back its sheen. What catastrophe will bring us back to ourselves this time? Expect things to get worse before they get better.

Beach is always on the look out for interesting books: drbeachcombing AT yahoo COM