A Poxy Invasion of Europe: 1340s May 23, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackbackSo here’s the thing. A month ago StrangeHistory put up a post asking what would have happened had Europeans arrived in the New World in the fifteenth and sixteenth century without viruses being involved. The question was would Europeans have managed to conquer American real estate? There were lots of interesting answers from readers: all now under the post. (Beach was particularly intrigued by the idea of Indians understanding the principle of immunisation). But let’s turn this on its head. Amerindian culture was destroyed because the ‘natives’ got punched with a double whammy: (i) men with gunpowder; and (ii) devastating epidemics. Europe too knew something about a devastating epidemic when, in the fourteenth century, the Black Death swept through the barrio, but Europe was lucky enough that an army did not arrive simultaneously. What would have happened in the fourteenth-century had a group of thirty thousand steppe warriors ridden out of the sun into eastern Europe, not so much a flagellum Dei (which does us all good from time to time) as a pistol shot to the forehead: would they have been able to conquer the sorry remains of Christian civilization?

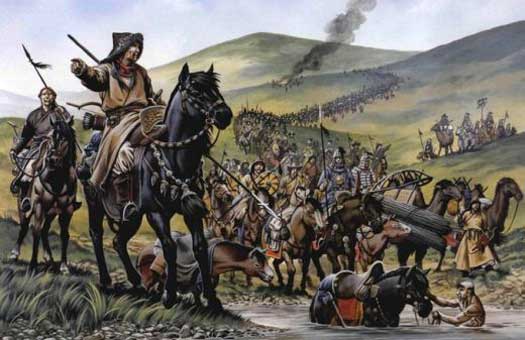

Of course, there was just such an army waiting to raise blood murder. The Golden Horde established itself in the thirteenth century and constantly bashed its head against Eastern European kingdoms, sometimes occupying, sometimes milking Dane-geld out of understandably terrified Slavs. This process had wound down by the 1240s but never underestimate a snotty Steppe warrior. Serbia was attacked in 1293, Thrace in 1337 and Europeans never really got the hang of killing their Asian enemies. Knights worked against knights and to some extent against Arabs, but not against superb light cavalry with a contempt for ‘chivalry’. In the 1340s, when the Black Death struck, the GH still had an operational army numbering tens of thousands of warriors: some of the finest light cavalry in the world; and this was an army that had showed itself precocious in learning the most interesting of the military techniques from the periphery of the Steppes.

Of course, the great problem for a Golden Horde scenario was that the Black Death seems to have affected the GH as much as it did European cities: or at least enough to kick the breath out of the Steppe armies. But let’s imagine for a second that GH immunity had built up in the decades before, or that the Black Death struck a generation later, when the GH had got over the worst what would have happened had the dust clouds appeared on the horizon? Bad things certainly, but would Europe, with its cities having lost at least half their populations have disappeared in the rubble? Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

25 May 2015: The great Mike Dash writes in with this.

Just a brief thought on your Golden Horde post. The limiting factor with regard to Mongol penetration of Europe, which – given that they had a century to push further than they actually did between their own arrival at the gates of Europe in the 1240s and the eruption of the black Death – can probably be considered critical was closely linked to the excellence of their light cavalry, which you so rightly draw attention to. That is the availability of pasture for large armies of horsemen. Bear in mind that the average Mongol soldier would have brought at least two horses with him on campaign and we’re talking sufficient grassland to feed say 100,000 steeds. If one plots the initial Mongol conquests against the distribution of steppe-lands, the correspondence is pretty clear to see, and this also explains the way in which the Mongols ruled over states such as Muscovy – remotely, using a tribute system. I don’t say that is the entire answer, mind, because after all Attila had got as far as western France 800 years earlier, and the Mongols did subdue Iran, China, and South East Asia as far as Java. So why they were able to go further there than they were able to push into Europe remains a bit of a puzzle, I’ll admit. A couple of factors do leap to mind: lack of experience with siege warfare (the Mongols only took China by co-opting local siege engineers into their armies), leadership (Kubilai Khan was surely a better ruler than Berke of the Golden Horde, and on the whole the khans of the Horde did not reign for very long, either), in-fighting (the Horde quickly divided into eastern and western polities, which helps to explain the rapid turnover of rulers), geopolitics (the gravitational ‘pull’ of the Mongol world lay far to the east of the Golden Horde’s territories, and so any political calculations mostly involved looking east; this in turn made territorial pushes to the west politically risky) and, perhaps most important of all, conversion (I’d suggest that the Ilkhanate was only able to rule Persia because of this, and the Golden Horde’s conversion to Islam not only ensured much stiffer resistance from their Christian enemies, but also tended to make them feel part of the Islamic world rather than the European one – see geopolitics above). You’ll be aware, of course, that the Black Death is traditionally supposed to have spread to Europe from Caffa, a Genoese port in the Crimea being besieged by the Mongols, who took to throwing plague-infested corpses over the walls with catapults. When I looked into this I was quite surprised to find not only that the story is still pretty widely accepted by historians, but also that there has been comparatively little work done on the plague in Asia at the time of the great contagion. The general presumption still seems to be that it spread from central Asia or even the Far East, but there seems to be no evidence that it wreaked similar levels of destruction there, nor that it spread east and south to other communities where it was not so prevalent (Japan say, or Australia). That has to imply far higher levels of immunity in that part of the world than in Europe. So, whatever other factors were in play, I doubt it was the plague that stopped the Mongols razing the cities of the west.

LTM has a good article on the plague in Asia.

KMH writes: The Mongols did seem to be unstoppable using tactics never seen before. There was one central weakness in their organization: it all depended on the single leader at the top. If he died (for whatever reason) the whole campaign would be arrested or discontinued until a replacement emerged. The same weakness is found in many primitive tribes – kill the chief or leader and the tribe loses its rationale for hostilities. Do great commanders live normal lives according to the pertinent mortality tables? I don’t think so – there is a significant element or feeling of destiny in their lives which many attest to. If there is anything to the destiny argument, then the answer is that Western Europe’s destiny precluded subjugation by the Mongols. Thanks to all!

31 May 2015: Bruce T an old friend of this blog writes: I happen to have a translation of Rene’ Grousset’s excellent 1939 opus, “The Empire of The Steppes; A History of Central Asia”, at hand.

Not to knock Mike’s post, but according to Grousset, an elite Central Asian horseman on the leading edge of an advancing horde normally had a string of mounts of over 10 horses. A Mongol horseman of the 12th-14th century used a string of horses numbering in the mid teens. The warrior would change horses on the fly, leaving the previous mount to be collected by following elements of the horde. The rapid movement this allowed,and tens of miles long unique crescent shaped line they used, is why Mongols were said to “appear out of nowhere”. Pasturage as Mike said, was limiting factor re; most Central Asian pulses into Europe.

One of the things that stopped these advances was the fact that dense forests then bisected the Northern European plain. The lack of pasturage, and limited mobility of lightly armored cavalry in such an environment, created an effective border on Central Asian horseman penetrating into western Europe.

That being said Genghis Khan was in the beginning stages of planning an invasion of western Europe at the time of his death. He felt that he had a divine mandate to conquer the Eurasian continent from the Pacific to the Atlantic. If he hadn’t kicked the bucket, Gregorian chants might have been replaced by Mongolian throat singing in the monasteries of Europe.