Hono Heke, A Maori Chief from Ireland?! May 3, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackIn the Middle Ages the Irish were for ever finding Gaels in surprising parts of the world. The soldier who pierced Christ’s side on the cross was Irish, Simon Magus was an Irish druid, etc etc. It is a shock to find, though, that this endearing habit lasted into the nineteenth century. In June and July 1846 newspaper reports appeared in the Irish press recording that, incredibly, Hono Heke, the exceptional leader of the Maori on the north island was from, wait for it, rural Tipperary!

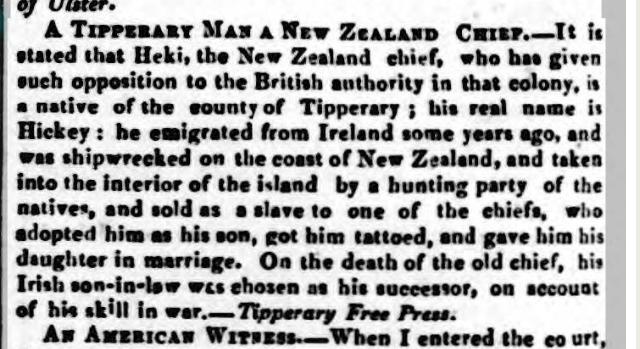

It is stated that Heki, the New Zealand chief, who has given such opposition to the British authority in that colony, is a native of the county Tipperary; his real name is Hickey [love this!]: he emigrated from Ireland some years ago, and was shipwrecked on the coast of New Zealand, and taken into the interior of the island by a hunting party of the natives, and sold as a slave to one of the chiefs, who adopted him as his son, got him tattooed, and gave him his daughter in marriage. On the death of the old chief, his Irish son-in-law was chosen as his successor, on account of his skills in war.

This brief report has to be parsed in two different ways: psychologically and historically. Let’s start with the psychology behind it. Of course, the Tipperary Irish, perhaps the most nationalist of all the country, would have loved the idea that one of their ‘lads’ was giving the Brits hell on the other side of the world, something they were singularly failing to do in Ireland at this date. In the summer of 1846 Heke was still outlaw after several notable battles against better armed Colonial troops and he would remain so until 1848 when a peace of kinds was made: he died in 1850 mourned by his people and with tributes being paid by his erstwhile British enemies. There is also the fact that the Maoris were always judged by nineteenth-century British and one imagines Irish opinion as being a cut above your typical ‘savage’, to use that uncomfortable Victorian word.

Historically the key point is surely that almost nothing was known about Hickey, sorry Heke’s origins and so this kind of absurd tale could grow up without anyone waving birth certificates in the face of a Tipperary story-teller. The tale seems to have sunk almost without trace (the ‘trace’ being trifling little news stories like the one above). In fact, the closet Google got this blogger was the Maori translation of it’s a Long Way to Tipperary, which was fun. And what does this canard really mean? Beach would read it as a wonderful Irish tribute to a people with whom they shared nothing save a dislike of British rule.

Just in case there is anyone out there who approves the Tipperary tale, bring us your proof: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

31 May 2015: ANL writes, ‘Although I share your mirth regarding the Irish origins of Hono Heke, there is a historical precedent!

You probably know all about this, but (with due thanks to Wikipedia):

Gonzalo Guerrero, a Spanish sailor from Palos de la Frontera, was shipwrecked (with others, most of whom did not survive) in pre-conquest Mexico. Guerrero became a famous war leader under Nachan Kaan, Lord of Chektumal, marrying his daughter Zazil Há, and fathering three children.

At Guerrero’s suggestion, a Maya army attacked the expedition of Francisco Hernández de Córdoba in 1517, killing many of Hernández’ men, most of them during a battle near the town of Champotón.

When Cortés arrived in 1519, Guerrero appears to have told his Maya friends and family that the Spaniards could die like other men. He led the Maya in campaigns against Cortés and his lieutenants, such as Pedro de Alvarado and the Panamanian governor Pedrarias. Alvarado’s instructions in his Honduras campaign included an order to capture Guerrero.

Oviedo reports Guerrero as dead by 1532, when Montejo’s lieutenants Avila and Lujón arrived again in Chectumal. Andrés de Cereceda, in a letter to the Spanish King dated August 14, 1536, writes of a battle that occurred in late June 1536 between Pedro de Alvarado and a local Honduran cacique named Çiçumba. The naked and tattooed body of a Spaniard was found dead within Çiçumba’s town of Ticamaya after the battle. According to Cereceda, this Spaniard had come over with 50 war-canoes from Chektumal early in 1536, to help Çiçumba fight the Spanish who were attempting to colonize his lands. The Spaniard was killed in the battle by an arquebus shot. Although Cereceda says the Spaniard was named Gonzalo Aroca, R. Chamberlain and other historians writing about the event identify the man as Gonzalo Guerrero. Guerrero was 50 years old when he died.