The Campestres, Romano-British Fairies? April 18, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient , trackbackFairies appear in nineteenth-century folklore collections, seventeenth-century spells, sixteenth-century plays, tenth-century charms and (at least in Ireland) early medieval tales. How wonderful it would be to drag the evidence back into the Roman period and beyond for our native fauns. One strategy for doing so has been to turn to Romano-British inscriptions which may (just possibly) record some of these classical fairies. Walter Scott recorded, in the early 1800s, an acquaintance of his pushing some toga-ed fairies.

Good old Mr. Gibb, of the Advocates’ Library (whom all lawyers whose youth he assisted in their studies, by his knowledge of that noble collection, are bound to name with gratitude), used to point out, amongst the ancient altars under his charge, one which is consecrated, Diis campestribus, and usually added, with a wink, ‘The fairies, ye ken.’ This relic of antiquity was discovered near Roxburgh Castle, and a vicinity more delightfully appropriate to the abode of the silvan deities can hardly be found.

There is no surviving British inscription with ‘diis campestribus’ [taken here as field gods] so this is likely an approximation of Scott’s but there are several British inscriptions that include the word campestribus using the dative plural to refer to a group of apparently female deities. Take this one from Castle Hill (Strathclyde) in what was occupied Northern Britain beyond Hadrian’s Wall.

Campestribus et Britann(ae) Q. Pisentius Iustus pr(a)ef(ectus) coh(ortis IV Gal)lorum v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) l(aetus) m(erito)

This stone records a dedication by Pisentius Iustus to Britannia and also to the campestribus. The tradition that the campestribus were fairies continued well into the nineteenth-century. One author, John Buchanan in 1867, recorded the fairy traditions of Peel Glen (where this stone was turned up), then span a lovely Romantic scene.

[The place] in moonlight, as I have seen it, is lonely and eerie, the silence broken only by the low rush of the rocky streamlet, the rustle of the night-wind among the flickering bushes, and its deeper moan through the tall black trees on the ancient soldiers’ height above, — standing in the moonbeams like funereal warders, round the now silent home of the long departed brave.

Buchanan went on to write:

It is a curious circumstance that this fairy tradition has some apparent countenance even from Roman times, for an altar was discovered in 1816, buried in the ground on the Castlehill slope, bearing an inscription by a Roman officer named Quintus Pisentius Justus… This altar was dedicated to ‘The Eternal Field Deities of Britain,’ — supposed to mean the elves, which on some memorable occasion may have scared the superstitious prefect and induced him, as the inscription states, in performance of a vow, to set up on this weird spot the curious memorial which has come down to us.

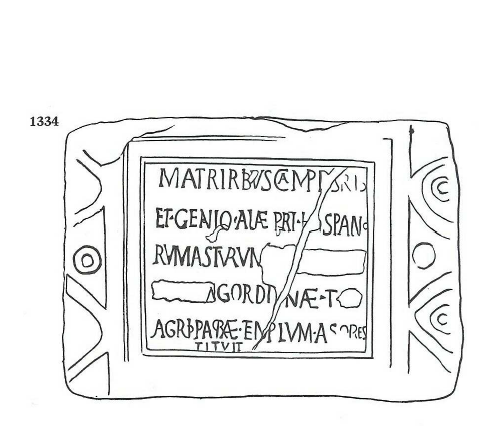

It is a lovely notion but unfortunately the Roman fairies crumble to dust when examined. There are several altars to the ‘campestribus’ in Britain. However, the following points should be noted about these mysterious beings (which are also referred to elsewhere in the Empire). Campester is the nominative form of a noun in Latin referring to plains, fields but also crucially to parade grounds. The campestres (nominative plural) are usually taken to be the gods or goddesses of the Parade Grounds, soldierly deities as the inscriptions to them are exclusively by soldiers (who are admittedly overrepresented in inscriptions). All the other dedications to these campestres are compatible with this hypothesis and we also have the word campester applied to deities with military associations: e.g. Mars Campester, Parade Ground Mars in Spain. Britain may be unique though in feminizing the gods of the campestres, the image at the head of this post has the ‘mother campestres’: though the answer for that is perhaps to be found in local mythology rather than fairylore if such a division even made sense at this date?

Do we have to give up our search for Romano-British fairies. Any other more reliable clues? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

30 April 2015: Lanark writes ‘I read with great interest your post on the Campestres/ Campestribus pn April 18, and as your man in Roman Scotland , I felt I must respond. My interest was kindled at your mentioning of the Castle Hill altar to Campestribus and Brittania (I attach a photo of the actual altar for your reference). Castle Hill was a small Antonine Wall Fort near Drumchapel in Glasgow. It is now just a ripple in the grass mostly within the ring of trees here. http://binged.it/1D2NgbM The chap who dedicated the altar, Pisentius Lustus, was one of a series of Frankie Howerd-ishly named Romans sent North to stand around in the rain and midges dedicating altars. Another chap who erected stuff was (I kid ye not) the wonderfully named Marcus Cocceius Firmus who dedicated a number of altars at another Antonine Wall Fort, namely Auchendavy (photo attached). These guys names surely put the camp in Campestribus. I think there is much agreement that Campestres/ Campestribus is a parade ground deity. I don’t know if you had heard of Cocceius Firmus before but his name is mentioned a few places in antiquity and Eric Birley wrote a fascinating little article which makes a very good case for Marcus Cocceius Firmus of the Auchendavy Antonine Altars being the self same Cocceius Firmus who was responsible for the return of roman prisoner, a convict woman sentenced to work in Salt Works and kidnapped by cruel kidnappers. Marcus Cocceius Firmus bought her back and re-claimed the money from the Imperial Treasury. It’s on the record! “A woman condemned, for a crime, to hard labour in the salt-works, was subsequently captured by bandits of an alien race; in the course of lawful trade she was sold, and by repurchase returned to her original condition. The purchase price had to be refunded from the Imperial Treasury to the centurion Cocceius Firmus.” I attach Eric Birley’s original (short)article for your leisurely perusal. Maybe there is a story in there for your blog. Birley places the salt works in Fife. I am unsure. Cocceius Firmus was based at Auchendavy which is nearly at the mid-point of the Antonine Wall so the salt works could have been at Dumbarton on the lower Clyde (West) or in Fife or the Lothian Coast (East). It’s hard to choose…

Thanks Lanark!