Binoculars, Wanted Posters and Green Dresses: Irish-British Relations Post Independence December 14, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackBy the end of 1916 the British establishment and the establishment in waiting of a future Irish state had come to loathe each other. The cause for this was not only the long history of rebellion and suppression (‘Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag…’), nor was it just the fighting of the Easter Rebellion: it had to do, above all, with the misguided British treatment of Irish rebels after the rebellion, when sixteen Republican leaders were rapidly and stupidly executed. Yet Britain and Ireland are neighbours and the respective leadership of the two countries would have to shake hands and negotiate through the rest of the twentieth century. A certain amount of imagination would be needed by both sides were British-Eire relations to work even moderately well. Happily, leaders on both sides showed this imagination.

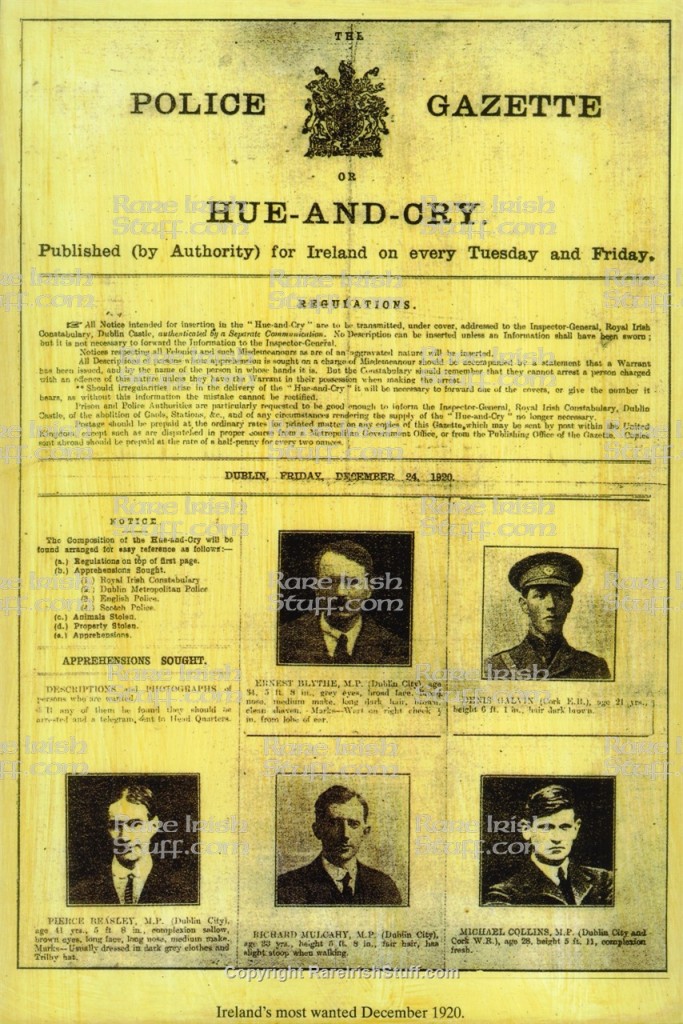

So, for example, when Michael Collins, finally met Churchill, 11 October 1921 in tense circumstances, he came face-to-face with a man who had encouraged his capture and judicial murder. As Churchill noted in his later tribute to Collins, after his death in an IRA ambush, in 1922: ‘We hunted him for his life, and he had slipped half a dozen times through steel claws.’ So how do men who mere weeks before had been so keen to annihilate each other come to terms? Churchill with his customary wit found a way to break the ice. Michael Collins reminded the British representative that a great deal of money had been offered for Collins’ capture in wanted posters (in one version of the story Collins gives Churchill a copy of said poster). Churchill, though, didn’t miss a beat and pulled out the poster of the reward offered for his capture during the Boer War, when he had escaped from a Boer prison camp. The two men then compared the prices that had been offered for them and levity entered in…

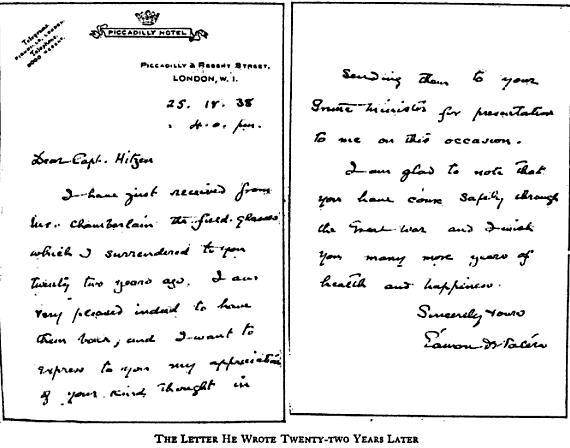

A similar gesture was attempted, with success, by Neville Chamberlain when he met the great Eamon De Valera, Ireland’s most dominant twentieth-century personality in Downing Street for the signing of a series of Anglo-Irish treaties in 1938. De Valera, it must be remembered, had almost been killed by the British in 1916. And Chamberlain ended the signing of treaties by handing over to De Valera a pair of binoculars that had been confiscated by a British officer, one Captain Hitzen, when De Valera surrendered his position in 1916 at the end of the Easter Rebellion: De Valera is pictured above being marched off. In this case the initiative seems to have come through Hitzen, who De Valera remembers as having treated him well in what must have seemed, twenty years, before as a prelude to execution. De Valera, a cold man but unquestionably a gentleman, wrote a letter to Hitzen expressing his gratitude for the returned binoculars.

In many ways, though the most impressive meeting of all was between Churchill and De Valera, in 1953, in Churchill’s final period in office. De Valera saw Churchill as the main obstacle to the end of partition: the main obstacle was, in fact, a solid Unionist majority, but let this rest… Churchill, on the other hand, could forgive De Valera his romantic nationalism but not the fact that Ireland had remained neutral in the Second World War. In fact, in Churchill’s victory speech after Victory in Europe, Churchill had dedicated much of his talk, listened to by the world, to berating Britain’s small western neighbour for her imagined crimes. De Valera fired back his reply, which was frankly far superior to Churchill’s original, setting out the rationale behind Ireland’s neutrality: it is a magnificent speech and well worth listening to. 17 Sept 1953 the two men, in any case, finally came together for lunch at Downing Street, the picture at the head of the post, captures a doddering Winnie and a diplomatic Dev. Churchill warmed to his old foe: ‘A very agreeable occasion. I like the man.’ De Valera was not so easily seduced. At Churchill’s death, twelve years later, De Valera stated simply and truly: ‘Sir Winston Churchill was a great Englishman, but we in Ireland had to regard him over a long period as a dangerous adversary’. De Valera being though De Valera he sent a private letter of condolence to Churchill’s widow.

Finally, this little survey of bizarre meetings between Anglo-Irish enemies and friends would not be complete without a picture of Queen Elizabeth II, dressed up like a leprechaun, shaking the hands of Martin McGuinness, a man who had for many years been an IRA commandment. The IRA it should be remembered had killed the Queen’s beloved uncle; McGuinness, meanwhile, had also lost many friends to Her Majesty’s forces, yet the smiles seem genuine (kind of)…

Other moments of British-Irish rapprochement? Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

14 Dec 2014: Mike Dash with a lovely account, ‘Interesting to read your account of hostility and rapprochement in Anglo-Irish relations today. It’s just a pity it omits what is arguably one of the most memorable (and telling) political exchanges of the last century: Lloyd George’s exasperated comment, during the difficult talks that led to the creation of the Irish Free State, that “negotiating with de Valera is like trying to pick up mercury with a fork.” Told of this, de Valera apparently replied: “Why doesn’t he use a spoon?” Thanks Mike!