Love Goddess #8: Simonetta Vespucci March 30, 2014

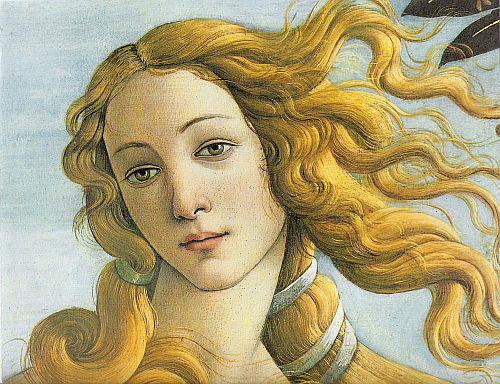

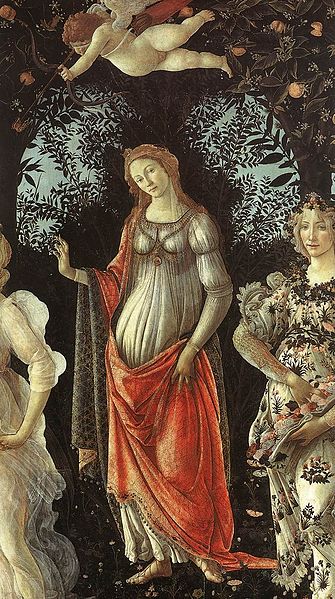

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackbackOur latest in the love goddess series (for a full list see below) is Simonetta Vespucci (obit 1476), a woman that had the reputation for being the most outstanding beauty of Florence at the apogee of that city’s golden age. We know that she came from Genova (her maiden name was Cattaneo de Candia), we know that she married into the Vespucci family in Florence (the family that produced American Amerigo), and we know too from near contemporary documentation that she was celebrated as a great beauty; we also know that she was just twenty three when she died in Florence of tuberculosis. There is a great deal more information out there about Simonetta but all of it is so very very doubtful. It is alleged that she is the beauty who appears in Piero Cosimo’s portrait of a woman with a snake necklace: the snake biting itself is a symbol of immortality but perhaps carries a hint of tuberculosis too? More insistently it is said that she appears again and again in Botticelli’s work as Venus in the Birth of Venus and as Venus (or another figure) in Primavera. There are some who claim too that Lorenzo fine sonnet ‘O chiara stella, che coi raggi tuoi…’ is dedicated to the recently deceased Genovese heart-throb. Other says that Guiliano (Lorenzo’s shallow brother) had raucous sex with her and rode out to joust with a banner made by Botticelli showing Simonetta as Athene. Here though we have the real condition of a love goddess, myth-making, for most of these ‘facts’ have to be brushed gently to one side or at least qualified: so Giuliano had a banner but there is no proof that it portrayed Simonetta.

The fundamental work here is Piero di Cosimo’s portrait, at the head of the post, sensibly titled by the Conde Museum (where it now resides) ‘A Woman Said to be Simonetta Vespucci’. The idea that the subject is Simonetta depends on the inscription at the base of the picture: but this inscription may be a later addition. If this sounds like inventing a problem where there isn’t one, consider that Piero was just fifteen when Simonetta died. In other words if this is Simonetta then it is a posthumous portrait: nothing too strange in Renaissance Florence but still it might give pause for thought. Let’s say that this is Simonetta: then we come to the problem of Botticelli who painted, again and again, a woman who is comparable though not to my eyes identical. Here below is ‘woman x’ in Venus and Mars, the Birth of Venus, in Primavera and two portraits of a ‘young woman’. Again I am not convinced all are the same person and have been struck by attempts to connect not only Venus but the three graces with Simonetta in Primavera! In any case, if Botticelli was painting Simonetta in some or all of those pictures then they were once more posthumous. It should also be noted here that there is a tale that Botticelli wanted to be buried at Simonetta’s feet: I’ve not though been able to trace this particular factoid to an early source and suspect a nineteenth-century guide book.

If Piero did paint Simonetta and if Botticelli’s woman x is the same then things become interesting. Botticelli is buried in the church of Ognisanti, in the Vespucci quarter of Florence: but he was born in that quarter and he seems to have worked for a time for the Vespucci so we don’t necessarily need to play the Simonetta card. Perhaps the most intriguing clue (?) of all is in Botticelli’s Venus and Mars where Mars’ head is surrounded by wasps, the sign of the Vespucci – their shield included seven wasps or vespe. A later, retrospective celebration of the marriage between Marco and Simonetta? As to Lorenzo’s poem, Lorenzo mentions no names (either in verse or in his accompanying commentary).

I had come to Simonetta wanting to decisively separate the bilge of legend from the memory of an astoundingly beautiful woman, who all too briefly lit the streets of western Florence in the late fifteenth century but whose face we have lost. Then I hesitated. The evidence is not enough to connect the images in the pictures with Simonetta, but there are perhaps just enough flimsy cobwebs between paintings to prevent an open mind from clam-like shutting and there is also, of course, that desire to see Simonetta somehow, somewhere. Perhaps the best conclusion is that in the late fifteenth century there does appear in Florentine art the beautiful strawberry blonde, a kind of secular Madonna figure, with pious eyes and whorish lips, who is inscrutable, beautiful and unobtainable: the Neo-Platonic ideal of eternal and energizing love best seen in Primavera in the varying female faces there. This strawberry blonde might have had something to do with central Italian hang-ups about blondes more generally: which is very evident in the fifteenth and sixteenth century Florentine art and can be seen when a yellow-haired American walks down any Italian street today. But it might be the transmuted echo of the memory of a single beautiful woman who enchanted her adopted city and died before the wrinkles set in. As heirs (reluctant or otherwise) of the Renaissance we all have Botticelli’s dream somewhere deep down inside us and if we want to call her Simonetta Cassiope need hardly throw a hissy fit…

Beach is always on the hunt for Love Goddesses: Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com. Here are our earlier efforts.

Love Goddess #7: The I Love You Wall

Love Goddess #6: Northumberlandia

Love Goddess #5: Agnes ‘Madonna’ Sorel

Love Goddess #4: Juliet, Verona and the Invention of Love