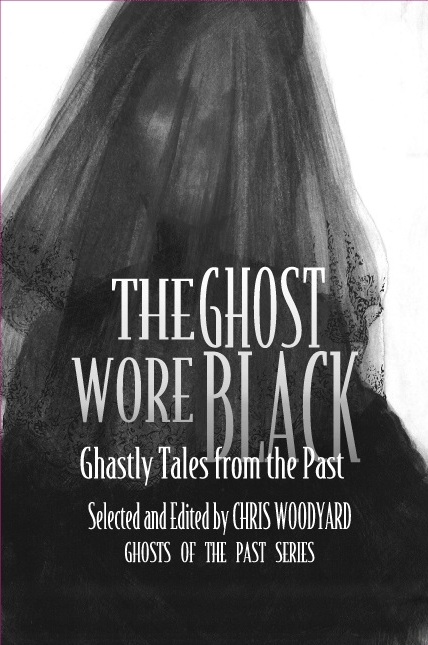

Review: The Ghost Wore Black October 30, 2013

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackThe Ghost Wore Black: Ghastly Tales from the Past is the latest in Ghosts of the Past series by Chris Woodyard. Anyone familiar with CW’s style will know by now what to expect. There are half a dozen thematic chapters, which takes us from devils, to wild men, to spring-heeled jack wannabees: ‘ghosts’ has to be understood here in the widest possible sense. Each chapter has a series of ‘new’ stories from generations-old American newspapers, not the normal read-it-already fodder of miscellanies and collections. (Of the scores of stories here Beach only recognized one.) Each story is preceded and rounded off by commentary. This commentary is worth reading for three reasons. First, CW has exquisite English: that ability to write with scanned prose that about one in ten published writers have. Second, CW is an accomplished historian. Watching her follow her sources down is like watching an accomplished cowboy tying a steer. It is elegant and inevitable and you almost feel sorry for those guys from 1871, as Chris chases them through the censuses and databases demanding the truth: ‘Did you or did you not see your mother’s decomposing face at the window?’ Third, CW has a couple of decades of informed Fortean reading behind her. She sees connections that others don’t see and this writer should note that in having sent several ‘academic’ articles to Chris over the years, the Ohio author has given more interesting insights than the anonymous referees that bestride the world like colossi. Another example of her insight: in reading the book Beach scribbled ‘pilgrim’s progress’ in the margin when a particular image came up: it was a bit tangential but there was something vaguely… Then, bang, the next page CW was discussing Pilgrim’s Progress though with full references and precise exegesis.

Beach’s favourite chapter was, forgive me, the fairy chapter. Actually the fairy chapter is called ‘Men in Black: Unearthly Entities’ and has only a few references to American dwarfs, but those were mysterious enough to satisfy Beach. The strange thing is that these dwarfs are not, well, dwarfs, they seem to be ghosts, but they are not ghosts of diminutive people or at least not always: OK one was a baby, one was a small sailor… It is all a bit confusing, but also fascinating and if CW has dug up 4 there must be another dozen out there waiting to be found. There is one extraordinary account of a dwarf in a brickyard, who when cut in half with a spade (!!!) ‘went up into the air about forty feet and the pieces reunited with lightning speed’ (97), then the dwarf vanished in the sky! In connection with this CW notes the curious fashion in which certain European fairies came across with emigrants: above all, perhaps the banshee? But other forms of fairy life, for example, the leprechaun or brownie did not. What ties some fairy beliefs to place and yet allows other fairies to get on the liners and cruisers heading for the New World? It would be tempting to put it down to ethnicity. In the same way that, say, certain ethnic groups were loyal to their food in America, other ethnic groups were loyal to their fairies. But as the presence of the banshee but the absence of the leprechaun suggests this explanation holds water like a sieve. It seems to be something, rather, to do with fairy type but again the family-oriented banshee, yes, but the family-oriented brownie, no? What is going on?

Another fascinating point that CW is necessarily alive to is the propensity of nineteenth-century American newspapers to invent ghost and paranormal stories. All of the stories quoted here are, by definition, incredible, but some lack the rough edges of an experience and seem rather to be literary productions. There is, for example, an excellent ghost story at the beginning of the book from the Grand Rapids Enquirer. This story could be placed next to James and Le Fanu in a ghost collection without embarrassment to the editor. Yet it purports to be fact and ends with sworn affidavits! CW rejects it, suggesting that it was inspired by two Edgar Allen Poe stories and whether this is its actual literary genealogy or not she is surely right that it is a fiction. But this fiction is a reminder that nineteenth-century American news men had few scruples about creating copy: whereas, in Beach’s experience, contemporary nineteenth-century British newsmen had either more scruples or more fear of the consequences of untruth. The classic example is, of course, the 1835 moon hoax in New York, but there are many, many more and some newspapers and some journalists were worse than others. CW writes, for example, about one Warren G. Harding (remember him?) at the Marion Star who, CW is always polite, ‘never met a ghost yarn or a big snake story he didn’t like’ (193). One of Beach’s problems with the revered Charles Fort is that, for all his experience with newspapers, CF rarely questions his sources: or even shows much of an awareness that his sources might contain biases and falsehood. In fact, this blogger would choose Chris Woodyard’s elegant, thought out, novel and suprising work any day over Fort’s endless scree slopes of the bizarre.

Any other quality reads: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

31 Oct 2013: Some words on Fort from Umbriel: ‘while Fort is frequently characterized as an ‘investigator of strange phenomena’, I think that’s always been a misnomer, and one that he himself would likely have objected to. He apparently refused membership in the Fortean Society founded in his honor, in the expectation that it would attract all manner of lunatic fringe ‘true believers’, when it was ‘true belief’ itself to which he was fundamentally opposed. He had much in common with his friend H.L. Mencken as a curmudgeonly critic of orthodoxy, but as another friend, Tiffany Thayer, put it in his introduction to Lo, noting Mencken’s criticism of Fort’s earlier work: ‘I tried to learn once, what H. L. Mencken had said of The Book of the Damned. He was going around busting things. One would think there would be some affinity. I could not learn. Now, Mr. Fort tells me that he called it ‘poppycock’ or something similar. Upon analysis that is understandable. Mr. Mencken, like Voltaire, had to ‘believe’ in science and its pronouncements to carry on against religion. It is incomprehensible to him that they may both be products of the same imbecilic urge to worship what is not readily explainable.’ I think Fort is more accurately seen as an ‘ideological nihilist’. His interest in the aberrant was chiefly as a means of throwing brickbats at orthodoxy of any kind. He was an advocate not of alternative inquiry, but rather of intellectual humility.’ Thanks Umbriel!