William Thornber and the Witches, Boggarts, Sorcerers and People of the Fylde June 7, 2013

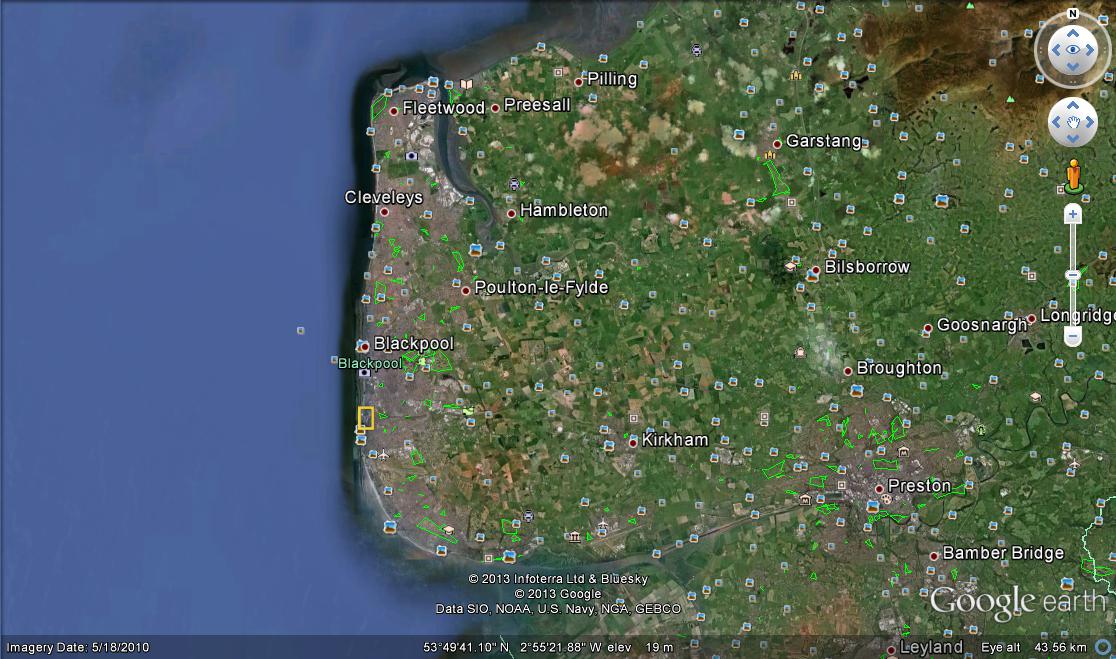

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackPart of the StrangeHistory project is to put up sources that for some reason have not made it onto Google Books and the like. In an attempt to do just this Beach spent a long hour typing out, yesterday, 3000 words from William Thornber’s The History of Blackpool and its Neighbourhood (Poulton 1837). I know, I know it doesn’t sound that interesting but the truth is that Thornber’s book is unusual. Most English folklore material (witches, fairies, ghosts and ghouls…) in British sources emerges after 1850. Before that date these things were seen as embarrassing relicts of an unhappy past. Whereas after 1850 they start to become as quaint as morris dancing and cream teas. Thornber is unusual in that he didn’t feel that normal reluctance to write about the popular beliefs of Blackpool, a hellish holiday resort on the north-west coast of England, and more importantly the countryside roundabout pre 1850. One late nineteenth-century scholar who read Thornber noted that Thornber could have collected much more and that by the 1880s the stories that the Blackpudlian alludes to had gone the way of the Commodore 74… It is true. But Beach is grateful for small mercies. Note though that when Thornber gets into superstition he raises his voice. Enjoy this little rave about the Catholics – this is the early nineteenth century, just a generation after the Gordon Riots – before we move onto sorcerers and other north-western ‘popery’.

Take another example of the awful superstition in which the country was wrapped, and of the prevailing ignorance cherished by the Popish church. The last evening in October was called the ‘Teanlay Night,’ or the fast of All souls. At the close of that day, till within late years, the hills, which encircle the Flyde, shone brightly with many a bonfire; the mosses of Marton &c, &c rivaling them with their fires, kindled for the avowed object of succouring their friends detained in the fancied regions of a middle state. A field, near Poulton in which the mummery of the ‘Teanlays’ was once celebrated, (a circle of men standing with bundles of straw, raised on high with forks,) is named Purgatory, by the old inhabitants; and this fact will hand down to posterity the ridiculous farce of lighting soul to endless happiness from the confines of their fabled prison-house. This custom was not formerly confined to one village or town in this neighbourhood, but was generally practiced by the Romanists as a sacred religion ceremony. The lamentable state of things, connected with the few books they had, which consisted principally of the marvellous histories of the saints of the Roman Calendar, cherished old superstitions and engendered new ones; the mind being ever ready to give a welcome to the greatest absurdities. Hence we hear of so many places, which were once the haunts of imaginary beings; no village, or ancient mansion, escaping the reputation of being infested by its ‘Boggart.’ Nor was belief in witchcraft discarded, but rather fostered; nay, I might mention the names of more than one old woman, not long ago dead, who were reputed dealers in the black art, and resorted to by the foolish and credulous, who were desirous of purchasing a peep into futurity. Every mishap was ascribed to the ill-nature of the witch; the cow, or horse, that died of old age, was bewitched. Such being the dread and infatuation with which she was regarded, we may conceive that numerous would be the preventives against her malevolence; and such was the case. A horse shoe, nailed to the door, protected the family domicile; a hag stone, penetrate with a hole, and attached to the key of the stable, preserved the horse within from being ridden by the witch, and, when hung up at the bed head, the church freed the cream from her presence: the baking of dough was protected the by a cross; and what housewife would, even now, fancy that her kneeding trough would be secure from the visitation of the foul fiend, did she not bar her approach during the night by the sacred symbol of the cross? Notwithstanding these precautions against the visits of the witch, when advice was requisite, under the loss of any property, the ‘wise man’ was the first person applied to, to enable the loser to regain it, and some books, which had once belonged to a celebrated clerk, of Mitton, were in great repute. Great faith was also attached to charms, to ameliorate the ills of life, sickness, pain, &c; thus we find our fathers, nay, even this generation, wearing a charmed ring, as a preventive against a disordered stomach, a belt against rheumatism; brimstone carried about the person, and a pair of shoes placed under the bed, the toes just peeping from beneath, were sure remedies against the cramp; warts were got rid of, by stealing a piece of raw beef, and after rubbing the affected parts, burying it in the ground; a snail, hung upon a thorn, was equally efficacious – as these consumed away, so also did the warts; a bag of stones, equal in number to the warts to be destroyed, thrown over the left shoulder, transmitted them to the person who chanced to pick them up. To particular persons was attached the virtues of stopping blood by a word, and a female of Marton, whose maiden name was Bamber, was so celebrated for her success in this branch of the science of charming, that, for twenty miles around her neighbourhood, she practiced her art. Even the devil was cast out, by some ‘mumbo jumbo,’ when, in the form of the ague, he was tormenting some sufferer by constant returns of his attacks; and I might name one, who, though superior in education to the generality, fancied he possessed the power of ‘casting him out’ by a charm which he inherited, and under this delusion, till of late years, was resorted to for relief by numbers. The rapid spread of knowledge is now fast dispersing the credulity which could hope for a cure from such ridiculous gifts; however, the phrase which is still retained, of casting out the ague, when medicine is administered, will ever preserve the fact, that it was once deemed a demoniacal possession. Charms were all powerful in the eyes of the vulgar, and applied by the children to the merest trifles; by charmed words the sting of the nettle was cured, and the snail was enticed from its shell by a well-known rhyme. Deplorable as was the ignorance in which these delusions originated, and by which they were fostered. I must not yet pause from my recital of others. Our fathers were great observers of omens, and had a budget of bad and good; when did the magpie cross their path, except the evil, which it forboded, was attempted to be averted by the sign of the cross, further consecrated by the unction of spittle? Many a family has been thrown into confusion, at the sight of a winding sheet in a candle, or the approach of a red-haired youth on the morn of a new year. Who was so daring as to commence a journey, take to himself a wife, or begin any undertaking on a Friday, unlucky as the day on which our Saviour’s blood was shed; and who would have hoped that his crop of onions would prove productive, had he failed to sow the seed on St Gregory, yclept, ‘Gregory-gret-Onion?’ Dreams were much regarded, and the number of books vended not very many years since, professing to interpret them, surpasses belief. Nor was the country destitute of those gifted individuals who boasted that they possessed the ‘second sight’ of Scottish notoriety; amongst those the names of Cardwell, of Marton, stands conspicuous, visited by men noted for their talents, yet credulous, and giving implicit faith to his marvelous tales of death foretold, and nightly visions seen. His sight of wraiths, however, was not always to be trusted to; on some intimation that his child was soon to be numbered with the dead, he conveyed sand to the church yard, to be ready for its grave; but the death thus anticipated did not happen; the child is still alive, and is now an active member of society, indicating, by an appearance of robust health, the promise of a life of many years. Fortune-telling, too, held a great sway in their estimation, in which the deaf and dumb had a peculiar gift of discernment. I will not weary my reader in relating by what a variety of means the trembling maiden gained a sight of her destined spouse, – how anxiously she awaited the eventful eve of All-hallows, – how earnestly she looked to trace her lover’s name on the prepared ashes, – how carefully she threw over the left shoulder the hemp seed, – visited the five-barred gate, – and with what patience she watched, on the feast of St. Agnes, the ‘pig tail,’ (a small candle) waiting the appearance of the passing shade of her pre-destined husband! The tea cup, cards, the spurting of a candle, &c were regarded as manifesting signs whereby the initiated might gain a glimpse of the future, or a prediction of his own lot in later life.

These customs, superstitions and delusions, once so prevalent in this portion of the country, are fast dying away; the traces of them are becoming fainter and fainter, and few more years of greater intercourse with the world will obliterate them. In proportion as the Gospel, and education dispel the dark mists of heathenism and Popish superstitions, in the same degree will be banished ignorance, which propagates such unmeaning secrets of heaven; and all will confess, that the omen, predicting the greatest happiness in this world and in the next, is a conscience void of offence towards God and man, a firm belief in the Scriptures, and a saving faith in the merits and atonement of a crucified Saviour.

Beach was actually a bit disappointed by this. He had hoped for more from Thornber. Luckily, he kept reading and towards the end of his book, in the section on Marton, Thornber pulls out more interesting details.

Before the erection and endowment of a charity school in Great Marton by Mr. Baines, in 1717, I can regard this township, now containing upwards of fifteen thousand souls, little less than a scene of moral destitution; and that gentleman must be highly eulogized as being, under God, a distinguished agent in dispelling the mists of ignorance and superstition which, to a lamentable extent, overshadowed it. An established place of worship, that valuable instrument in the hands of God for enlightening the dark understandings of his creatures, had not as yet reared its head as a beacon to warn the ignorant against the wiles of stan, and as a refuge for the desolate. Thus debarred from the means of education and of grace, who can wonder that ignorance should prevail? Though that ornament of an English village, a protestant church, has been erected, yet superstition, the offspring of ignorance, is more prevalent here than in any neighbouring district. Natural religion has a tendency to produce either formality or superstition; and such I apprehend is the effect of the magnificent grandeur of the ocean on unenlightened man, that nonce can constantly look upon it without its variety of moods soothing his mind to a melancholy sadness, and exciting and cherishing a mysterious veneration for the father of the universe. To this awe, created ‘genio loci,’ I ascribe the existence of the lingering remains of those superstitions on the borders of the sea which more inland communities have long rejected. I do not apologize for again introducing this subject, since ‘trivial circumstances, which show the manners of the age, are often more instructive, as well as more entertaining, than the great transactions of wars and negotiations, which are nearly the same in all periods, and in all the countries of the world.’

The ancient custom of walking ‘withershins’ (as the weather shines,) when leaving home to commence a journey, or about to undertake any particular enterprise, is still observed, though in a less degree than formerly; what bridal party would omit it; and, when advancing to the altar to have their marriage solemnized, would pursue any other way than that down the fortunate isle? The practice of performing courses sunwise around their benefactors, and blessing them, was long usual in the Highlands; and at this day the fisherman of the Shetland isles, in order to insure a favourite voyage, turns his boat sunwise the moment the anchor is weighed. The custom is said to be of Scandinavian origin, probably introduced by the Danish Vikingr or priesthood. Another method of insuring good luck is by enclosing a poor tabby in durance vile within the oven; times and seasons, the phases of the moon, are closely observed when the first operation of cutting the infant’s nails and hair is to be performed, which, for a whole year, have been guarded from the scissors of the anxious mother. Bacon receives a more excellent flavour when the pig is slaughtered at a particular time; this precept was given in the time of Dr. Johnson, in one of the English almanacks, ‘ To kill hogs when the moon was increasing and the bacon would prove better in boiling.’ The extracted tooth must be thrown into the fire and sprinkled with salt; for if it be unfortunately lost, no rest or peace will be enjoyed till it is again found. Almost universal belief is attached to the notion that bees hum loudly, as if swarming, on the night preceding old Chrstmas-day, thus exhibiting to the vulgar mind a positive proof that the birth of the Saviour should be observed on that day, and not on the one established by the alteration of the Calendar. Charming is in high repute, the jaundice being cured at one shilling per head by an individual residing in the Fold, who, by some family secret of incantation performed on the urine of the afflicted person, which is suspended in a bottle over the smoke of his fire, boasts he can effect a perfect cure in the most difficult cases. Let me close this ridiculous list of still lingering feelings of superstition by recording the different kind of boggarts, – beings, whose existence was once accredited by selecting for haunts certain places in this portion of the Fylde, and who, in many instances, still continue to hold their sway I the heated imaginations of the credulous. The wandering ghost of the homicide and of the steward of injustice, or of the victim of murder, – for instance the headless boggart of White-gate lane, – is the most numerous class, the one suffering for his sins, and other unable to rest in peace till requital be made. To this may be added the death-warner attached to particular families. The Walmsley’s of Poulton were haunted y one of this description, always making its appearance with alarming noises before the decease of one of the family. But there was a sort of *lubber fiends [here Thornber quotes Milton in a footnote], which may be named brownies: these, by kindness, might be gained over to perform some of the drudgery of a farm; of this progeny is the ancient one of Rayscar and Inskip, which at times kindly housed the grain, collected the horses, and equipped them ready for the market, but at others playing the most mischievous pranks. The famous boggart of Hackensall hall had the appearance of a huge horse, which was very industrious if treated with kindness; thus we hear that every night it was indulged with a fire, before which it was frequently seen reclining, and, when deprived of this indulgence by neglect, it expressed its anger by fearful outcries. Boggarts, under the shapes of huge horses, were common, and I am inclined to think that they must have some affinity with the Kelpie, or water-horse, of Scotland. The fairies of our fathers were supposed to have their residence in the earth; hence old pipes, of the reign of James, dug out of the ground, and known by the name of fairy pipes; they were kind, good-natured creatures, at times seeking the assistance of mortals, and in return liberally rewarding them. They had a favourite spot between Hardhorn and Staining, at a cold spring of water, called fairies’ well to this day. Most amusing stories are told around the district concerning these imaginary beings. I select the following: – A poor woman, when filling her pitcher at the above named well, in order to bathe the weak eyes of her infant child, was mildly accosted by a handsome man, who presented her with a box of ointment, and told her it would a specific remedy – grateful for the gift, yet love for the child, made her mistrustful, so that she first applied it to one of her own. Some short time afterwards she saw her benefactor at Preston, stealing corn from the mouth of the sacks open for sale, and, much to his amazement, accosted hi. Onhis inquiry how she could recognize him, since he was invisible to all else around, she explained the means whereby she became enabled to distinguish him, and pointed to the powerful eye – when he immediately struck it out.

A milkmaid observing a jug and a sixpence placed at her side by an invisible goblin of this kind, filled it and took the money; this was repeated for weeks, till, overjoyed with her good fortune, she could not refrain from imparting it to her lover – but the jug and the sixpence never again appeared.

A ploughman hen engaged in his daily labour, on hearing a plaintive cry, ‘I have broken my speet,’ hastily turned round, and beheld a lady holding in her hand a broken spittle, a hammer and nails, and beckoning him to repair it; on his compliance she vanished from his sight into the earth; but not before she had liberally rewarded him with good cheer for his service.

Precious fairy lore from the north west that had disappeared by the time of the great folklorists of the 1880s. Enjoy this last detail about Staining Hall.

The registers of Poulton Church testify the respectability and numerous offspring of the Singletons of Staining; and within its walls many of them lie interred, without a single monument to record the spot. Staining, in old writings, is termed a lordship, and at this day pays a dutchy rent. Its hall has a ‘Boggart,’ according to tradition, the wandering ghost of a Scotchman, murdered near a tree, which has since recorded the deed by perfuming the ground around with a sweet odour of thyme.

Beautiful. Any information on Thornber or the folklore of the Fylde: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com