Who Needs Anti-Aircraft Guns When You Have Saints? March 7, 2013

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackIn Norman Lewis’ brilliant, astounding Naples ’44, the British writer has many curious and memorable passages from his diary of that year. However, this is one of Beach’s favourites.

At Pomigliano [north-east of Naples] we have a flying monk who also demonstrates the stigmata. The monk claims that on an occasion last year when an aerial dog-fight was in progress, he soared up to the sky to catch in his arms the pilot of a stricken Italian plane, and bring him safely to earth. Most of the Neapolitans I know – some of them educated men – are convinced of the truth of this story.

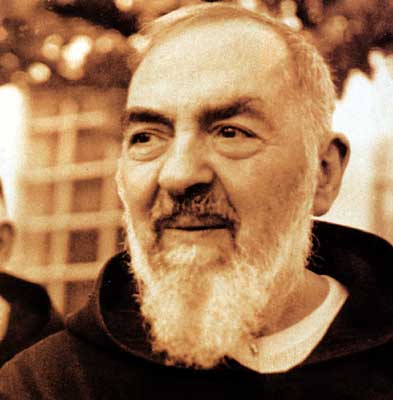

Weird things happen in and around Naples and the Neapolitans are an extraordinarily superstitious people who have never really bidden farewell to the middle ages. However, the flying monk is actually a famous and well documented individual. Lewis put in a footnote – and NL hated footnotes – that this was no less a person than ‘the celebrated Padre Pio’, Italy’s most important twentieth century saint. The list of Padre Pio’s miracles is both sensationalistic and long: they appear to belong to the eighteenth century, rather than the tame old 1900s. However, the tales of sky miracles concerning PP are or became even more dramatic. Here is a typical passage borrowed from a pious webpage:

‘There are many stories concerning allied pilots who attempted to bomb San Giovanni but were stopped by an apparition of a ‘monk’ standing in the air with his arms outstretched,’ says Ruffin. ‘There are fliers who swore that they had sighted a figure in the sky, sometimes normal size, sometimes gigantic, usually in the form of a monk or priest. The sightings were too frequent and the reports came from too many sources to be totally discounted. Several people from Foggia, where thousands were killed in the air raids, said that a bomb, falling into a room where they had huddled, landed near a photograph of Padre Pio. They claimed that when it exploded, it ‘burst like a soap bubble.’ Others reported that while bombs were raining down upon the city, they cried, ‘Padre Pio, you have to save us!’ While they were speaking, a bomb fell into their midst, but did not explode.

Of course, any Foggians with a photograph of PP who did not enjoy the soapy Allied bombs would presumably not have survived to tell the tale. But let’s concentrate, instead, on PP aerial fights against the Allies. Here is the key passage from an outstanding page that has gathered all the relevant sources together from Italian and translated them. We have taken the original Italian from elsewhere.

This event, which is to say the least unheard of, was directly witnessed [Beach would translate a direct witness, not quite the same] by the general of Aeronautica Italiana Bernardo Rosini, who at that time was part of the ‘United Air Command’ operating out of Bari with the Allied air forces. ‘Each time that the pilots returned from their missions,’ General Rosini told me, ‘they spoke of this Friar that appeared in the sky and diverted their airplanes, making them turn back. Everyone laughed at these incredulous stories. But since the episodes kept recurring, the Commanding General decided to intervene personally. He took command of a squadron of bombers to destroy a cache of German war materials that was said to be right in San Giovanni Rotondo. Up until that time, no one had ever succeeded in going in that direction because of the presence in the air of that mysterious phantasm which forced the airplanes back. Since this had been happening for some time, at the base there was much apprehension. We were all curious to see the results of this operation. When the squadron returned, we went over to ask what had occurred. The American general was quite upset. He recounted that as soon as they arrived near the target, he and his pilots had seen rising up into the sky the figure of a monk with his hands held high. The bombs dropped all by themselves, falling in the woods, and the planes turned in retreat, without any intervention on the part of the pilots. That evening, the episode was the main topic of conversation. Everyone was wondering who was this specter which the airplanes mysteriously obeyed. Someone said to the Commanding general that at San Giovanni there lived a Priest with the stigmata whom everyone considered a saint, and that perhaps he was the very one responsible for diverting the planes. The general found this hard to believe, but as soon as it was possible, he wished to go there to find out. After the war, the general, accompanied by a few pilots, arrived at the Capuchin Convent. As soon as he crossed the threshold of the sacristy, he found himself facing a number of Friars, among whom he recognized immediately the one who had stopped his airplanes. Padre Pio went up to meet him, and putting a hand on his shoulders, said to him: ‘So it is you, the one who wished to do away with all of us.’ Astonished at seeing and hearing the Friar, the general kneeled before him. Padre Pio had spoken in his usual Benevento dialect, but the general was convinced that the Priest has spoken in English. The two became friends. The general, who was a Protestant, converted to Catholicism.

Di questo episodio, che è poco definire inaudito, fu testimone diretto il generale dell’Aeronautica italiana Bernardo Rosini che, allora, faceva parte del ‘Comando unità aerea’ operante a Bari a fianco delle forze aeree alleate. Ogni volta che i piloti tornavano dalle loro missioni’, mi raccontò il generale Rosini, ‘parlavano di questo frate che appariva in cielo e dirottava i loro velivoli facendoli tornare indietro. Tutti ridevano increduli ascoltando quei racconti. Ma poiché l’episodio si ripeteva, e con piloti sempre diversi, il generale comandante decise di intervenire di persona. Prese il comando di una squadriglia di bombardieri per andare a distruggere un deposito di materiale bellico tedesco, che era stato segnalato proprio a San Giovanni Rotondo. Fino a quel momento nessuno era mai riuscito a dirigersi in quella direzione per la presenza nel cielo di quel misterioso fantasma che dirottava gli aerei. Dopo quello che stava accadendo da qualche tempo, a terra c’era molta tensione. Eravamo tutti curiosi di conoscere il risultato di quell’operazione. Quando la squadriglia rientrò andammo a chiedere informazioni. Il generale americano era sconvolto. Raccontò che, appena giunti nei pressi del bersaglio, lui e i suoi piloti avevano visto ergersi nel cielo la figura di un frate con le mani alzate. Le bombe si erano sganciate da sole, cadendo nei boschi, e gli aerei avevano fatto una inversione di rotta, senza alcun intervento dei piloti. Quella sera l’episodio era stato al centro di discorsi e di discussioni. Tutti si chiedevano chi fosse quel fantasma cui gli aerei avevano misteriosamente obbedito. Qualcuno disse al generale comandante che a San Giovanni Rotondo viveva un frate con le stigmate, da tutti considerato un santo e che forse poteva essere proprio lui il dirottatore. Il generale era incredulo ma disse che, appena gli fosse stato possibile, voleva andare a controllare. Dopo la guerra, il generale, accompagnato da alcuni piloti, si recò nel convento dei Cappuccini. Appena varcata la soglia della sacrestia, si trovò di fronte a vari frati, tra i quali riconobbe immediatamente quello che aveva fermato i suoi aerei. Padre Pio gli si fece incontro e, mettendogli una mano sulla spalla, gli disse: ‘Dunque sei tu quello che voleva farci fuori tutti.’ Folgorato da quello sguardo e dalle parole del frate, il generale si inginocchiò davanti a lui. Padre Pio aveva parlato, come al solito, in dialetto beneventano, ma il generale era convinto che il frate avesse parlato in inglese. I due divennero amici. Il generale, che era protestante, si convertì al cattolicesimo.

There are dozens of versions of these stories all that can apparently be traced back to the testimony of General Rosini (obit 1999). Rosini certainly existed: though he was unlikely to have been a general in 1933 when he was just 30, which makes us wonder whether the other biographical details above are correct. There is a brief biography of him in Italian that shows he was a pious man. Indeed, as often happens in these cases the earnest disciple is more likeable than the austere saint he follows. But, without questioning Rosini’s honesty, something which can almost certainly be taken for granted, we must ask whether there is anything in this tale. Rosini did not – pace the translation above – see any of the things he is describing, at best he heard them from witnesses. Nor is it likely to have come from PP, who did not harp on about his own miracles, perhaps because many of those reported did not happen. There is no question that Rosini is recounting a very satisfying story. But what can be said for and against said story?

Leaving aside the physical problems – flying and shape-shifting monks – this story bears all the signs of being a tale. It is a little too satisfying: it seems crafted or perhaps smoothed over through frequent telling. (This frequent telling continues online: follow this link to see how the story continues to be simplified and smoothed over: indeed, in this account Rosini has become the American general!) An American ‘general’ (more likely a lower rank) could have flown with his men on a difficult mission. If the ‘general’ had really wanted to he could have visited San Giovanni, though why wait till after the war, when he just had to wait for the line of battle to shift a little to the north? That waiting to the end of the war seems a very Italian way of looking at things. Then there is the ‘general’ dropping to his knees… This is just not very Anglo-Saxon, even in moments of intense admiration English or Americans don’t tend to fall to the floor, they saw ‘wow’ or take a photo on their i-phone. But such behaviour would be par for the course for a histrionic southern Italian. Of course, let’s say that these are the additions of an Italian story-teller. This does not mean that there is not something genuine behind this tale. However, it a warning that we are not dealing with a classic documented account.

Let’s move on to the biggest problem of all with this report. Where are the allied witnesses? Where is the general who converted? Seeing ‘foo fighters’ and other curious things in the sky excited Allied pilots, who were often rather garrulous about them once hostilities had ended. If you had seen a giant flying Capuchin monk… Well, let’s say that the letters home would have been kept in the family Bible (or in the folder of the mental institution where your family brought you). Rosini’s account presupposes dozens of different Allied men who would have seen this marvel. Yet not a single one has gone on record. Turn now to this witness account of an American serviceman who was in the USAF, a little later than the incidents described but who knew nothing or at least writes nothing about a flying friar. William Carrigan clearly saw something marvelous here and couldn’t shut up about it. Indeed, the event understandably changed his life.

At Christmas time, 1943, the 15th Air Force, to which I was attached, arrived from North Africa to take over the great German air bases around Foggia on the Adriatic across from Naples. I was assigned to the American Red Cross Field Office in Foggia. Little did I think that I was soon to travel up a steep winding road on the mountain of Gargono which forms the spur of the boot of Italy. Two soldiers who told me that they heard of a Capuchin Monk at a monastery in the town of San Giovanni Rotondo who had the wounds of the crucifixion in hands, feet and side, and they wanted me to take them to Mass in order to meet him. A snow storm was in progress on the mountain. We were taken into the sanctuary where Padre Pio was saying Mass. We knelt on the cold marble floor on the side not ten feet from Padre where we could observe his every movement. As he began the consecration he seemed to be in great pain, shifting his weight from side to side, hesitating to begin the words of consecration which he would start and repeat-biting them off with a clicking of his teeth as if in great pain. His cheek muscles twitched and tears were visible on his cheeks. He reached for the chalice and jerked back his hand because of the pain in the wound which was fully visible to me. After his communion he leaned over the altar for sometime as if he was in communion with Jesus. Later I learned that at this time he presented his many spiritual children to Our Lord offering his own suffering for them.

It has repeatedly been suggested that Pio kept his wounds open using bicarbonate of soda. We have no knowledge and no opinion because stigmata grosses Beach out. Any other evidence for or against anti-aircraft saints? Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

8 March 2013: A couple of emails accusing me of anti-Pio bias (Jenny and HH). There may be something in this. I’m keen on saints but there is something about PP that frightens me… However, having had a day to think about this post can I just add: I like very much Rosini as revealed in the Italian source above. I would trust him. My suspicion is that whoever first quoted him got his biographical details mixed up. You cannot, in WW2 Italy, be a general at 30! How many other facts did they confuse about where he was and whom he heard these stories from? In the end, and I didn’t think of this when I was writing, NL is our ur source: I wonder if there is anything in Italian that early? Also JCE writes in with a literary thought. Dr. B, regarding the reports of Padre Pio’s ascension among dogfighting aircraft above Naples, and the claims of reports of pilots and others having seen priest-like figures, some of which were giants, in the air, I am reminded of striking imagery from Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. It has stayed with me over 25 years. Perhaps you know the sprawling wormball of a book, which is almost beyond description; indeed, for me it was often beyond comprehension. But in the initial segment it deals with the experiences of Allied pilots who have flown combat missions over Europe in WWII. I hardly know why, but I was stunned by Pynchon’s description of three (?) angels standing impossibly huge in the depths of the ocean as they impassively watched the air combat. I have thought back to that imagery over the years, and have always felt an inexplicable but almost palpable awe. Although in my memory the angels did not intervene, I wonder whether Pynchon was aware of the Padre Pio stories. Thanks to HH, Jenny and JCE.

31 March 2013: EC writes: Like JCE I too thought of Gravity’s Rainbow when I read your piece on the sky saint. Here is the text from the novel that JCE is remembering: “But out at the horizon, out near the burnished edge of the world, who are these visitors standing . . . these robed figures—perhaps, at this distance, hundreds of miles tall—their faces, serene, unattached, like the Buddha’s, bending over the sea, impassive, indeed, as the Angel that stood over Lübeck during the Palm Sunday raid, come that day neither to destroy nor to protect, but to bear witness to a game of seduction.” Perhaps also interesting is the description of the Angel of Lübeck incident from earlier in the novel – it resembles the Padre Pio story not a little, and it touches on the unreliability of paranormal reportage that you discuss in your post: “Basher St. Blaise’s angel, miles beyond designating, rising over Lübeck that Palm Sunday with the poison-green domes underneath its feet, an obsessive crossflow of red tiles rushing up and down a thousand peaked roofs as the bombers banked and dived, the Baltic already lost in a pall of incendiary smoke behind, here was the Angel: ice crystals swept hissing away from the back edges of wings perilously deep, opening as they were moved into new white abyss. . . . For half a minute radio silence broke apart. The traffic being: St. Blaise: Freakshow Two, did you see that, over. Wingman: This is Freakshow Two—affirmative. St. Blaise: Good. No one else on the mission seemed to’ve had radio communication. After the raid, St. Blaise checked over the equipment of those who got back to base and found nothing wrong: all the crystals on frequency, the power supplies rippleless as could be expected—but others remembered how, for the few moments the visitation lasted, even static vanished from the earphones. Some may have heard a high singing, like wind among masts, shrouds, bedspring or dish antennas of winter fleets down in the dockyards . . . but only Basher and his wingman saw it, droning across in front of the fiery leagues of face, the eyes, which went towering for miles, shifting to follow their flight, the irises red as embers fairing through yellow to white, as they jettisoned all their bombs in no particular pattern, the fussy Norden device, sweat drops in the air all around its rolling eyepiece, bewildered at their unannounced need to climb, to give up a strike at earth for a strike at heaven . . . . “Group Captain St. Blaise did not include an account of this angel in his official debriefing, the W.A.A.E officer who interrogated him being known around the base as the worst sort of literal-minded dragon (she had reported Blowitt to psychiatric for his rainbowed Valkyrie over Peenemünde, and Creepham for the bright blue gremlins scattering like spiders off of his Typhoon’s wings and falling gently to the woods of The Hague in little parachutes of the same color). But damn it, this was not a cloud. Unofficially, in the fortnight between the fire-raising at Lübeck and Hitler’s order for “terror attacks of a retaliatory nature”—meaning the V-weapons—word of the Angel got around. Although the Group Captain seemed reluctant, Ronald Cherrycoke was allowed to probe certain objects along on the flight. Thus the Angel was revealed. Carroll Eventyr attempted then to reach across to Terence Overbaby, St. Blaise’s wingman. Jumped by a skyful of MEs and no way out. The inputs were confusing. Peter Sachsa intimated that there were in fact many versions of the Angel which might apply. Overbaby’s was not as available as certain others. There are problems with levels, and with Judgment, in the Tarot sense. . . . ” . Thanks EC!