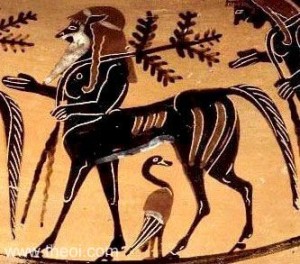

Centaurs in Deepest Arabia August 21, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient , trackback

Phlegon of Tralles is not a Greek author of the first rank. Indeed, he rarely comes up in conversation among students of the ancient except for a reported remark concerning the death of Christ.

But this small-time second-century writer, who was born in south-west Turkey and who lived at least until 137 AD, is a minor cult figure for Beachcombing because Phlegon liked recording strange facts. Among these a description of a centaur, which he had seen with his own eyes, in the Emperor Hadrian’s storehouse (34-35).

A centaur was discovered in Saune, a city of Arabia, on a high mountain that is full of deadly poisons. The drug has the same name as the city and as a killing substance it is fast-working and effective.

The centaur was taken alive by the king [of the place?] who sent it to Egypt with other gifts for the Emperor Claudius. It ate meat. But it did not like the change of air and died and so the prefect of Egypt had it embalmed and sent on to Rome.

At first it was shown in the palace. Its face was more savage than a human face, its arms and its fingers were hairy and its ribs were joined to its front legs and its stomach. It had strong hooves of a horse and its mane was tawny. However, because of the embalming process its mane and its skin had become dark. In terms of its size it was not as usually shown, but it was not much smaller either.

It is said that there were other centaurs in the aforementioned city of Saune.

As to the one sent to Rome, the sceptic can go and examine it for himself, for, as I noted above, it has been embalmed and it is kept in the Emperor’s storehouse.

It’s enough to give you goose-bumps isn’t it? Certainly, it got Beachcombing running up and down the stairs.

In the Emperor Tiberius’s time (AD 14-37) it had been announced to the world – through the unlikely medium of a Greek sea captain – that the god Pan had died. Then a generation later a few of Pan’s knights are spotted cavorting among the poison ivy in deepest Arabia.

However…

And here starts the depressing descent into detail and denial. If you like Phlegon’s Centaur a lot perhaps you shouldn’t read on.

Phlegon was writing in the early second century. Claudius was emperor 41-54 AD, which means these details about a venomous mountain allegedly come from the best part of a century before. It is true that Phlegon likely had access to palace records – he was one of Hadrian’s freedmen – but even so this is not contemporary evidence.

Then there is the city Saune that has never been identified and the poison Saune that has also never been identified. Neither are recorded anywhere else.

But like a cavalier trumpeter Pliny the Elder comes riding to the rescue. In his Natural History (77-79 AD) Pliny has the following reference (7, 35) to centaurs

Claudius Caesar writes that a centaur was born in Thessaly and died the same day; and in his reign we actually saw one that was brought here for him from Egypt preserved in honey. One case is that of an infant at Saguntum which at once went back into the womb, in the year in which that city was destroyed by Hannibal.

Claudius Caesar scribit hippocentaurum in Thessalia natum eodem die interisse, et nos principatu eius adlatum illi ex Aegypto in melle vidimus. Est inter exempla in uterum protinus reversus infans Sagunti quo anno deleta ab Hannibale est.

Beachcombing draws the reader’s waning attention to the central sentence. In the reign of Claudius a Centaur was brought from Egypt. It tallies perfectly with Phlegon’s story, though unfortunately there is none of the details of an Arabian outpost of centaur relicts and the honey was long gone by Phleg’s time.

Note too that Claudius wrote, in one of his several lost works, about the centaur, which suggests an all too predictable interest on the part of the ‘scholar’ Emperor. This may explain the Arabian king’s and particularly the Prefect of Egypt’s actions in getting one to him.

In Adrienne Mayor’s outstanding The First Fossil Hunters, the wanw scholar has a fascinating chapter on centaurs (228-253), including the Centaur of Saune. She concludes that centaur bodies in the ancient world were fair-ground magic: animal bodies sewn together by hoaxers.

How dare she!

Beachcombing would like to say that Phlegon, with his mouth open in Hadrian’s storeroom, would have been up to spotting the stitch marks. However, he does not think that that kind of pernickety observation was one of Phleg’s strong points.

There are a number of other ancient centaur sightings. But Beachcombing has been pained by the lack of medieval and early modern encounters: any offers? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

He hopes to visit the Centaur of Volos on another occasion.