Baring-Goulds’ Pixies August 23, 2012

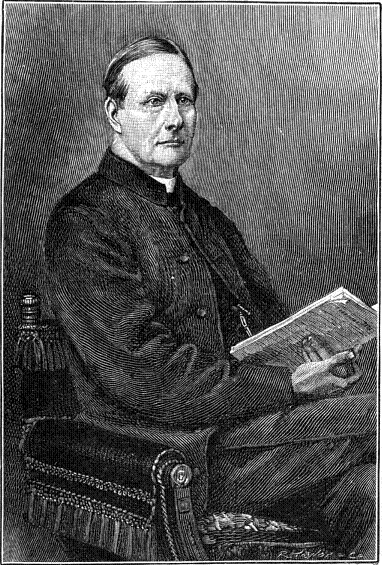

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackbackAnyone interested in fairies will read in many places of Sabine Baring-Gould’s childhood encounter with pixies. But how many will have actually read the original? In an effort to correct this Beach sat this afternoon tapping out the following text only to discover that someone else got there first: a bunch of heroes over at the wiki source project. In any case, here is Sabine recalling his encounter. Enjoy:

It was whilst on the journey to Montpellier over the stony plain, with a hot sun smiting down on me, seated on the box beside my father, whilst the postillion rode one of the two horses, that I experienced a curious sensation. I saw, or fancied that I saw, a crowd of little imps or dwarfs surrounding the carriage, running by the side of the horses, and some leaping on to their backs. One was astride behind the post-boy. They were dressed in brown, with knee breeches, and wore little scarlet caps of liberty. I remarked to my father on what I saw, and he at once removed me into the shade, within the carriage. I still saw the little creature for awhile, but gradually they became fewer and finally disappeared altogether. The vision was due to the sun on my head, but why the sun should conjure up such a vision is to me inexplicable. I cannot recall that my nurse at Bratton had ever spoken to me of, and described, the Pixies.

Other members of SBG’s family had also been favoured. Beach is not clear whether his wife was child or adult in this encounter:

It is a curious fact that my wife has seen one, or things that she has, in Yorkshire. In a green lane at Horbury [nb there are different versions of this in different editions: why?] she saw, or fancied she saw, a little man about two feet in height, clothed in green, sitting in the hedge. He had black beady eyes, and looked hard at her. She stood observing him for a while, and then, when he began to make faces at her, she became frightened, and ran away.

My son Julian, one day in 1883, was in the garden picking pea-pods, between two rows of peas, when he saw a little dwarf in brown with a red cap looking at him, and walking towards him. He was so frightened that he ran away and came into the house, white as ashes, and told me and his mother what he had seen. He was then aged six [footnote about gardeners materialism]. In both these cases the apparitions may be traced to sun on the head, but why take such similar forms?

SBG rounds off his account with some thoughts on the passing of the fairies. It is melancholy stuff, particularly the ‘pulsating’ hearts of the pixies, but very beautiful.

Plenty of stories are told, more or less circumstantially, of the ‘Knockers’ or gnomes of mines believed in Cornwall, Wales and in Germany. They may be seen in Mrs Hardinge Britten’s Nineteenth Century Miracles, 1884. But this will suffice. Mr C.G. Isham, of Lamport Hall, erected a rock garden in his grounds and peopled it with a crowd of gnomes made of terracotta.

How notable in the progress of mankind in knowledge is the fact that before the opening of a door hitherto shut, another door that has swung wide for generations should be slammed and double-bolted. For untold ages our ancestors had believed airy world. The little soulless people had been seen by men of good report, their songs had reached wondering ears, their good deeds and their malicious tricks were commonly related; but, almost suddenly, that is to say, in my lifetime, belief in the existence of pixies, elves, gnomes, has melted away; and in its place a door has been opened, disclosing to our astonished eyes a whole bacterial world, swarming with microbes, living, making love, fighting; some beneficial and others noxious—an entirely new world to us now such as America was to wondering Europe in the sixteenth century.

According to Addison, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, “There was not a village in England that had not a ghost in it, the churchyards were all haunted, every large common had a circle of fairies belonging to it, and there was scarce a shepherd to be met with who had not seen a spirit.” It was the same at the opening of the nineteenth century; and now all the spiritual world has vanished out of sight and is lost to the mind. Not a child knows aught now of its occupants. We have cast aside Oberon, Titania, Robin Goodfellow, the Brownie, Wag at the Wa’, and the Wild Huntsman with the Gabelrachet. Their place has been usurped by the Bacilli, by Schizophyta, Sphæro bacteria, Micro bacteria, Desmo bacteria and Spiro bacteria. What Shakespeare of the future will think of giving us a Bacteriological Midsummer’s Night’s Dream?

In the midst of the Tavy valley rises a mass of rock above the brawling and sparkling river, in spring clothed in bluebells, in summer redolent with thyme, and in autumn flushed with heather. Formerly it went by the name of the Pixy Castle, and it was held to be inhabited by the “good people” as the pixies were called. It was said that on Sundays they clustered on the rock, listening to the Mary and Peter Tavy Church bells, trusting that, though Christ had not died for them, nevertheless the bells did bring to them a promise of ultimate salvation.

As a young boy I have sat on the Pixy Castle, and thought of the elfin folk, yearning after that salvation, which is so lightly esteemed by many of us mortals, as they hearkened to the call of the church bells, and endeavoured to detect a promise in their peal. All that is over. No one ever accords these little beings a thought. Not a soul in Peter and Mary Tavy parishes considers how their mothers told of the little hearts on Pixy Rock pulsating to the distant bells.

We have to pay a price for every new acquisition, and the opening to us of the recently discovered world of microbes has followed on the banishment of the world of the Elves. Scientifically we have gained much. Imaginatively we have lost a great deal.

I have recalled old fancies, old dreams; and a shadow of regret has passed over my heart at the poetic loss we had sustained by the exile of the fairies. But when, out of health, I sip Lactor Bulgariensis with Bacillus Metchnicoffii souring it, I rest satisfied with the thought that the exchange has been of practical utility.

Nor is this all. There has come about a revulsion in popular feeling as to the spirits of men after death. In place of looking up to the souls gleaming in the light of Paradise, as we once were led to believe, now we are told that they hover about the ‘Horse Shoe’ in Tottenham Court Road, so as to catch a whiff of Player’s Navy-cut, or haunt a lawn-tennis ground in order to sniff up the fragrance of Glen Livet whisky, without having to pay war price for it.

Beach would be interested in any other encounters with fairies from autobiographies: there seem to be a few around – drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com