Escaping the Guillotine March 4, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackCapital punishment: it’s been a while. Beachcombing was thinking about close escapes from death penalty. There are two types of these, of course: either royal screw ups on the part of executioners or daring escapes at the point of death. The first category would include John Lee and a few others who somehow survived a hanging: unfortunately most other forms of state-inflicted death leave far less room for manoeuvrings. The second category would include… well, whom? Beach has been able to come up with lots of examples but all appear in fiction and many of those in comic books. So any genuine escapes at the point of death? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com To get the ball rolling Beach offers up this tale of Henri Chateaubrun who was allegedly sentenced to death in the ‘Terror’ because a Jacobin fell in love with his wife.

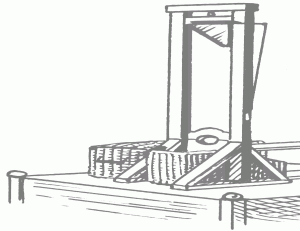

The next morning a number of carts were backed up to the door of the concierge, and a soldier in the prison called the names of twenty-one men who were to forth to execution. Among them was Henri Chateaubrun. They all walked out of the carts, some erect, all of them showing in their pale and haggard features the mark of death. Standing in the carts, they were driven towards the Seine and crossed it by a bridge entering the Place de la Revolution, since called the Place de la Concorde. There stood the guillotine with persons to work it ready to lop off twenty-one heads, and there stood a crowd kept back by soldiers, to witness the grewsome [sic] sight. The carts stopped besides the machine and the victims descended from the carts.

And now began a work that even an implement so well adapted to the purpose found it difficult to perform. Each one of the prisoners, hatless and with his hands tied behind his back, in turn stepped up to it, was laid upon it, strapped to it; the knife fell, his head rolled into the basket and his body was removed to make room for the next victim. Fifteen of the twenty-one had been executed when the guillotine refused to work. Whether the knife got wedged in the grooves or whether the machinery that raised the ax or that which detached it after it had been raised got out of order doesn’t matter. Something had gone wrong, and those in charge of the executions were unable to fix it.

The proceedings were stopped, and a messenger was sent for mechanics to put the guillotine in order. This required time. Waiting is not conducive to discipline. The soldiers who were there to keep the crowd back grew lax, and by the time workmen had arrived people had elbowed their way close upon the remaining six men standing in line waiting for the repairs on the machine that was to make corpses of them.

‘Get back!’ cried the guards, shoving the crow with the buts of their muskets. This was repeated so often that at last very little attention was paid to it. Chateaubrun presently found himself in the first line of spectators. Then, instead, of being in the line next [to] the guillotine, he found himself in the second. In the pushing that continued he was wedged back into the third line and at last was at the back of the crowd that was there to see his head cut off.

There was something radically wrong with the guillotine. The men fixing it hammered and pulled and screwed and unscrewed. Meanwhile the day was ended, and it was growing dark. Chateaubrun, considering the sight of his execution not worth so long a wait, quietly walked away.

The Place de la Concorde is at the beginning of the Champs d’Elysces. Chateaubrun, ever moment expecting to be missed, concealing as well as he could his tied hands, his heart beating wildly, passed into the Champs d’Elysces eager to run, but forcing himself to walk leisurely. There he made his way onward in the shadow of the trees. Finally, when he had gone far enough from the scene of his intended execution, meeting a man coming toward him he said: ‘M’sier, a friend of mine just now, who is a great wag, tied my hands behind my back and ran away with my had. Kindly unloosen me.’

The man of course did so and Chateaubrun was free to go. But is it a true story? Rather worryingly there is a similar tale about a man called Antoine Gaspard de Châteaubrun. Beach then smells the distinct though not unpleasant whiff of cobblers. For anyone with access Beach learns in another place that ‘This ” histoire merveilleuse,” [the one recounted about Henri rather than Antoine] as the French narrator rightly calls it, will be found in the memoirs of the Comte de Vaublanc, who also, but for his own adroitness, had been shaved by the national razor.’ Mmmmm