The Rocking Stone Unrocked February 10, 2012

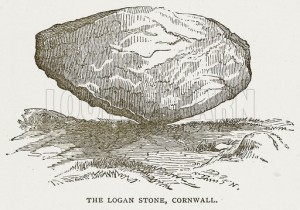

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackThe mother of all busy days today as students clamor for assistance and daughters for entertainment. Beach hope that readers will forgive him for offering up this story from his winter reading about Cornwall in the south-west of Britain. Our author is describing the Loggan Stone, aka the Logan Stone of Treen.

This far-famed rock rises on the top of a bold promontory of granite, jutting far out into the sea, split into the wildest forms, and towering precipitously to a height of a hundred feet. When you reach the Loggan Stone, after some little climbing up perilous-looking places, you see a solid, irregular mass of granite, which is computed to weigh eighty five tons, supported by its centre only, on a flat, broad rock, which, in its turn, rests on several others stretching out around it on all sides. You are told by the guide to turn your back to the uppermost stone; to place your shoulders under one particular part of its lower edge, which is entirely disconnected, all round, with the supporting rock below; and in this position to push upwards slowly and steadily, then to leave off again for an instant, then to push once more, and so on, until after a few moments of exertion, you feel the whole immense mass above you moving as you press against it. You redouble your efforts–then turn round–and see the massy Loggan Stone, set in motion by nothing but your own pair of shoulders, slowly rocking backwards and forwards with an alternate ascension and declension, at the outer edges, of at least three inches. You have treated eighty-five tons of granite like a child’s cradle; and, like a child’s cradle, those eighty-five tons have rocked at your will! The pivot on which the Loggan Stone is thus easily moved, is a small protrusion in its base, on all sides of which the whole surrounding weight of rock is, by an accident of Nature, so exactly equalized, as to keep it poised in the nicest balance on the one little point in its lower surface which rests on the flat granite slab beneath. But perfect as this balance appears at present, it has lost something, the merest hair’s-breadth, of its original faultlessness of adjustment. The rock is not to be moved now, either so easily or to so great an extent, as it could once be moved. Six-and-twenty years since, it was overthrown by artificial means; and was then lifted again into its former position. This is the story of the affair, as it was related to me by a man who was an eyewitness of the process of restoring the stone to its proper place.

And the story is an entertaining one.

In the year 1824, a certain Lieutenant in the Royal Navy, then in command of a cutter stationed off the southern coast of Cornwall, was told of an ancient Cornish prophecy, that no human power should ever succeed in overturning the Loggan Stone. No sooner was the prediction communicated to him, than he conceived a mischievous ambition to falsify practically an assertion which the commonest common sense might have informed him had sprung from nothing but popular error and popular superstition. Accompanied by a body of picked men from his crew, he ascended to the Loggan Stone, ordered several levers to be placed under it at one point, gave the word to “heave”–and the next moment had the miserable satisfaction of seeing one of the most remarkable natural curiosities in the world utterly destroyed, for aught he could foresee to the contrary, under his own directions!

But Fortune befriended the Loggan Stone. One edge of it, as it rolled over, became fixed by a lucky chance in a crevice in the rocks immediately below the granite slab from which it had been started. Had this not happened, it must have fallen over a sheer precipice, and been lost in the sea. By another accident, equally fortunate, two labouring men at work in the neighbourhood, were led by curiosity secretly to follow the Lieutenant and his myrmidons up to the Stone. Having witnessed, from a secure hiding-place, all that occurred, the two workmen, with great propriety, immediately hurried off to inform the lord of the manor of the wanton act of destruction which they had seen perpetrated.

The news was soon communicated throughout the district, and thence, throughout all Cornwall. The indignation of the whole county was aroused. Antiquaries, who believed the Loggan Stone to have been balanced by the Druids; philosophers who held that it was produced by an eccentricity of natural formation; ignorant people, who cared nothing about Druids, or natural formations, but who liked to climb up and rock the stone whenever they passed near it; tribes of guides who lived by showing it; innkeepers in the neighbourhood, to whom it had brought customers by hundreds; tourists of every degree who were on their way to see it–all joined in one general clamour of execration against the overthrower of the rock. A full report of the affair was forwarded to the Admiralty; and the Admiralty, for once, acted vigorously for the public advantage, and mercifully spared the public purse.

The Lieutenant was officially informed that his commission was in danger, unless he set up the Loggan Stone again in its proper place. The materials for compassing this achievement were offered to him, _gratis_, from the Dock Yards; but he was left to his own resources to defray the expense of employing workmen to help him. Being by this time awakened to a proper sense of the mischief he had done, and to a tolerably strong conviction of the disagreeable position in which he was placed with the Admiralty, he addressed himself vigorously to the task of repairing his fault. Strong beams were planted about the Loggan Stone, chains were passed round it, pulleys were rigged, and capstans were manned. After a week’s hard work and brave perseverance on the part of every one employed in the labour, the rock was pulled back into its former position, but not into its former perfection of balance: it has never moved since as freely as it moved before.

It is only fair to the Lieutenant to add to this narrative of his mischievous frolic the fact, that he defrayed, though a poor man, all the heavy expenses of replacing the rock. Just before his death, he paid the last remaining debt, and paid it with interest.

Any other cursed stones, rocking or otherwise? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

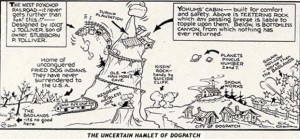

11/2/2012: KMH remembers Coral Castle in Florida. The 9-ton gate is nicely balanced so that a child can move it. Laurence has Teetering Rock in Dog Patch in mind.

Invisible writes in: I had to laugh out loud at the Admiralty getting involved with the Lieutenant and the rocking stone. Here’s an article about the cursing stone of Cumbria: And another cursed stone. Thanks KMH, Laurence and Invisible!!

22/2/2012: Sword and Beast writes in: ‘300 km south of Buenos Aires, there is a pampean city named Tandil, which, in the indigenous mapuche language, means “beating rock”. This is a reference to a 300 ton boulder which stood, quite impressively, on the edge of a rocky foothill, the “piedra movediza”. It was common practice to place bottles or other things under its base to see them break. There are good pictures. Among the many legends that surround the moving stone, there is one involving a mapuche human sacriffice of a lover (whose heart would then beat in stone) and a mention that General Rosas, the then Governor of Buenos Aires and “conqueror of the desert” (actually mostly the Pampas), has tried to bring it down with several horses, without success. The bolder toppled on February 29th, 1912, probably due to vandalism or mine explosions nearby, and split into three pieces at the bottom of the hill. In 2007, a hollow replica was cemented in the same place where the original stood, creating the world’s first “moving rock” that does not move.’ Then Moonman sends in some precious pages from Corliss. ‘Of course, Corliss has a section in Ancient Infrastructure 63-68 on this topic. He mentions the New York USA Peekskill rocking stone which shows people can’t help but try to destroy wondrous things as well as Cromwell’s armies purposely destroying rocking stones because of Druid association. I include scans of the section of interest for your examination only, not sharing on the Internet due to copyright.’ Beach is going to infringe just a little to include some of Corliss’ thoughts on British material: ‘Rocking stones have received the most attention by British amateur and professional archaeologists. This is understandable because standing stones and stone circles dot much of their countryside. France also boasts a few rocking stones. More are found in Asia but we have no details. The British enthusiasm for rocking stones infected New England, which, like Britain, is strewn with glacier debris. Some of these North American boulders either rock today or have been rockable in the past. The older American scientific journals carry many accounts of these unstable stones. Today, though, rocking stones are relegated to amateur archaeology publications… It is also true that rocking stones present a challenge to vandals, and numerous unstable stones have been pushed or levered off their bases. In addition, rocking stones have pagan affinities. Oliver Cromwell’s armies, for instance, deliberately destroyed rocking stones for their connections to the Druids. For several reasons, then the record of rocking stones is incomplete.’ Thanks Moonman and S&B and another salute to the great Corliss!