The Allendale Wolf January 24, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackAs this has been the season of the werewolf Beachcombing thought that today he would introduce the last English wolf, for yes, unfortunately the British Isles no longer have any of the howling ones.

The conventional answer – and Beachcombing, in happier days, planned a book on British Dodos – is that the last English wolf – Irish and Scottish wolves are another matter: another post another day – was killed in the reign of Henry VII (1485-1509). Certainly Juliana Barnes included the wolf in her Book of St Albans (1486) and versifies as if the animal was still around and biting at the end of the fifteenth century.

Now though for the less conventional answer. Charles Fort – that great recorder of the strange – offers the following story in his Lo! Beachcombing has not the slightest idea what to make of this, but enjoyed the details so much that he felt them worth sharing. If anyone can fill in any gaps or point to other (perhaps local) publications do please let Beachcombing know: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

In October, 1904, a wolf belonging to Captain Barnes of Shotley Bridge, twelve miles from Newcastle [and incidentally an old Beachcombing stomping ground, excellent Chinese restaurant there], England, escaped and soon afterward, killing of sheep were reported from the region of Hexham, about twenty miles from Newcastle… A story of a wolf in England is worth space, and the London newspapers rejoiced in this wolf story. Most of them did, but there are several that would not pay much attention to a dinosaur-hunt in Hyde Park.

Special correspondents were sent to Hexham, Northumberland. Some of them because of circumstances that we shall note, wrote that there was not a wolf, but probably a large dog that had turned evil. Most of them wrote that undoubtedly a wolf was ravaging, and was known to have escaped from Shotley Bridge. Something was slaughtering sheep, killing for food, and killing wantonly, sometimes mutilating four or five sheep, and devouring one. An appetite was ravaging in Northumberland. We have impressions of the capacity of a large and hungry dog, but upon reading these accounts, one has to think that they were exaggerations, or that the killer must have been more than a wolf. But according to the developments, I’d not say that there was much exaggeration. The killings were so serious that the farmers organized into the Hexham Wolf Committee, offering a reward, and hunting systematically. Every hunt was fruitless, except as material for the special correspondents, who told of continuing depredations, and revelled in special announcements.

It was especially announced that, upon December 15th, the Haydon foxhounds, one of the most especial packs in England would be sent out. These English dogs, of degree so high as to be incredible in all other parts of the world went forth. It is better for something of high degree not to go forth. Mostly in times of peace arise great military reputations. So long as something is not tested it may be of high renown. But the Haydon foxhounds went forth. They returned with their renown damaged…

There are not only wisemen: there are wisedogs, we learn. The Wolf Committee heard of Monarch, ‘the celebrated bloodhound’. This celebrity was sent for, and when he arrived, it was with such a look of sagacity that the sheepfarmers’ troubles were supposed to be over. The wisedog was put on what was supposed to be the trail of the wolf. But, if there weren’t any wolf, who can blame a celebrated bloodhound for not smelling something that wasn’t? The wisedog sniffed. Then he sat down. It was impossible to set this dog on the trail of a wolf, though each morning he was taken to a place of fresh slaughter. Well, then, what else is there in all this? If, locally, one of the most celebrated intellects in England could not solve the problem, it may be that the fault was in taking it up locally.

Fort then gets characteristically fevered noting that there had been a religious revival in 1904-05 and that lights in the sky had been seen. Then back to the wolf…

Slaughter in Northumberland – farmers, who could, housing their sheep, at night – others setting up lanterns in their fields. Monarch, the celebrated bloodhound, who could not smell something that perhaps was not, got no more space in the newspapers, and, to a woman, the inhabitants of Hexham stopped sending him chrysanthemums. But faith in celebrities kept up, as it always will keep up, and when the Hungarian Wolf Hunter appeared, the only reason that a brass band did not escort him, in showers of torn-up telephone books, is that, away back in this winter, Hexham, like most of the other parts of England, was not yet Americanized. It was before the English were educated. The moving pictures were not of much influence then. The Hungarian Wolf Hunter, mounted on a shaggy Hungarian pony, galloped over hills and dales, and, with strange, Hungarian hunting cries, made what I think is called the welkin ring. He might as well have sat down and sniffed. He might as well have been a distinguished General, or Admiral, at the outbreak of a war.

Four sheep were killed at Low Eschelles, and one at Sedham, in one night. Then came the big hunt, of December 20th, which, according to expectations, would be final. The big hunt set out from Hexham: gamekeepers, woodmen, farmers, local sportsmen and sportsmen from far away. There were men on horseback, and two men in ‘traps’, a man on a bicycle, and a mounted policeman: two women with guns, one of them in a blue walking dress, if that detai is any good to us. They came wandering back, at the end of the day, not having seen anything to shoot at. Some said that it was because there wasn’t anything. Everybody else had something to say about Capt. Bains. The most unpopular person, in the north of England, at this time, was Capt. Bains, of Shotley Bridge. Almost every night, something, presumably Capt. Bains’ wolf, even though there was no findable statement that a wolf had been seen, was killing and devouring sheep.

Then, as is CF’s wont, we move onto spontaneous combustion and handclapping before zigzagging back to the North East.

On both sides of the River Tyne, something kept on slaughtering [sheep]. It crossed the Tyne, having killed on one side, then killing on the other side. At East Dipton, two sheep were devoured, all but the fleece and the bones, and the same night two sheep were killed on the other side of the river.

‘The Big Game Hunter from India!’ Another celebrity came forth. The Wolf Committee met him at the station. There was a plaid shawl strapped to his back, and the flaps of his hunting cap were considered unprecedented. Almost everybody had confidence in the shawl, or felt that the flaps were authoritative. The devices by which he covered his ears made beholders feel that they were in the presence of Science. Hexham Herald ‘The right man, at last!’ So finally the wolf hunt was taken up scientifically. The ordinary hunts were going on, but the wiseman from India would have nothing to do with them. In his cap, with flaps such as had never before been seen in Northumberland, and with his plaid shawl strapped to his back, he was going from farm to farm, sifting and dating and classifying observations: drawing maps, card-indexing his data. For some situations, this is the best of methods: but something that the methodist-wiseman cannot learn is that a still better method is that of not being so tied to any particular method. It was a serious matter in Hexham. The ravaging thing was an alarming pest. There were some common hunters who were unmannerly over all this delay, but the Hexham Herald came out strong for Science ‘The right man in the right place, at last!’

There are some distractions of poultry killings (likely an otter) and then the finale.

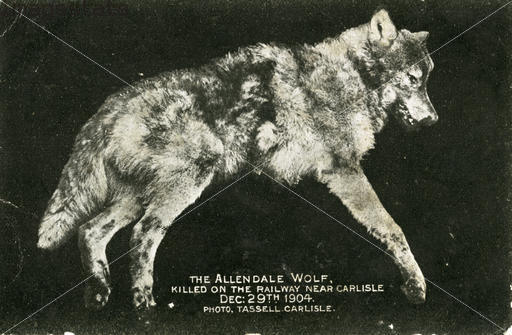

December 29 ‘Wolf killed on a railroad line!’ It was at Cumwinton, which is near Carlisle, about thirty miles from Hexham. The body was found on a railroad line – ‘Magnificent specimen of male gray wolf – total length five feet – measurement from foot to top of shoulder, thirty inches’.

But then a problem from which Fort derived much satisfaction.

Captain Bains, of Shotley Bridge, went immediately to Cumwinton. He looked at the body of the wolf. He said that it was not his wolf. There was doubt in the newspapers. Everybody is supposed to know his own wolf, but when one’s wolf has made material for a host of damage suits, one’s recognitions may be dimmed. This body of a wolf was found, and killings of sheep stopped.

But Capt. Bains’ denial that the wolf was his wolf was accepted by the Hexham Wolf Committee. Data were with him. He had reported the escape of his wolf, and the description was on record in the Shotley Bridge police station. Capt. Bains’ wolf was, in October, no ‘magnificent’ full-grown specimen, but a cub, four and a half months old. Though nobody had paid any attention to this circumstance, it had been pointed out, in the Hexham Herald, October 15.

Fort seems to be exaggerating here. He himself implies that some London journalists had been onto this fact from the beginning – see above.

The wolf of Cumwinton was not identified, according to my reading of the data. Nobody told of an escape of a grown wolf, though the news of this wolf’s death was published throughout England. The animal may have come from somewhere far from England. Photographs of the wolf were sold, as picture postal cards.

Beachcombing would love to purchase one of these: here’s hoping that ebay.co.uk does service.

People flocked to Cumwinton. Men in the show business offered to buy the body, but the decision of the railroad company was that the body had not been identified, and belonged to the company. The head was preserved, and was sent to the central office, in Derby.

There is something that is acting to kill off mysteries. Perhaps always, and perhaps not always, it can be understood in common place terms… In the newspapers, about the middle of February, appeared a story that Capt. Alexander Thompson, of Tacoma, Washington – and I have looked this up, learning that a Capt. Alexander Thompson did live in Tacoma, about the year 1905 – was walking along a street in Derby, when he glanced in a taxidermist’s window, and there saw the supposed wolf’s head. He recognized it, not as the head of a wolf, but the head of a malmoot, an Alaskan sleigh dog, half wolf and half dog. This animal, with other malmoots, had been taken to Liverpool, for exhibition, and had escaped in a street in Liverpool. Though I have not been able to find out the date, I have learned that there was such an exhibition, in Liverpool. No date was mentioned by Capt. Thompson. The owners of the malmoot had said nothing, and rather than to advertise, had put up with the loss, because of their fear that there would be damages for sheep-killing. Not in the streets of Liverpool, presumably. No support for this commonplace-ending followed. Nothing more upon the subject is findable in Liverpool newspapers.

Fort though remains sceptical:

Liverpool is 120 miles from Hexham. It is a story of an animal that escaped in Liverpool, and, leaving no trail of slaughtering behind it, went to a distant part of England, exactly to a place where a young wolf was at large, and there slaughtered like a wolf. I prefer to think that the animal of Cumwinton was not a malmoot. Derby Mercury, February 22 – that the animal had been identified as a wolf, by Mr. A. S. Hutchinson, taxidermist to the Manchester Museum of Natural History. Liverpool Echo, December 31 – that the animal had been identified as a wolf, by a representative of Bostock and Wombell’s Circus, who had travelled from Edinburgh to see the body.

Fort’s theories then become unprintable – at least for the purposes of this blog – and involve divine electricity. Beachcombing would implore any reader who has not yet had the pleasure of reading Fort to do so: the text above has been edited to get to the essential about the wolf and naturally Fort’s prose and thesis has suffered.

And then there is the final flourish.

Farm and Home, March 16 – that hardly had the wolf been killed, at Cumwinton, in the north of England, when farmers, in the south of England, especially in the districts between Tunbridge and Seven Oaks, Kent, began to tell of mysterious attacks upon their flocks. ‘Sometimes three or four sheep would be found dying in one flock, having in nearly every case been bitten in the shoulder and disembowelled. Many persons had caught sight of the animal, and one man had shot at it. The inhabitants were living in a state of terror, and so, on the first of March, a search party of 60 guns beat the woods, in an endeavour to put an end to the depredations.’ A big dog? Another malmoot? Nothing? ‘This resulted in its being found and dispatched by one of Mr. R. K. Hodgson’s gamekeepers, the animal being pronounced, on examination, to be a jackal.’ The story of the shooting of a jackal, in Kent, is told in the London newspapers. See the Times, March 2. There is no findable explanation, nor attempted explanation, of how the animal got there. Beyond the mere statement of the shooting, there is not another line upon this extraordinary appearance of an exotic animal in England, findable in any London newspaper. It was in provincial newspapers that I came upon more of this story. Blyth News, March 4 ‘The Indian jackal, which was killed recently, near Seven Oaks, Kent, after destroying sheep and game to the value of £100, is attracting attention in the shop windows of a Derby taxidermist’. Derby Mercury, March 5 – that the body of this jackal was upon exhibition in the studio of Mr. A. S. Hutchinson, London Road, Derby.

Beachcombing may have not being paying attention, but is he not right in saying, if – BIG IF – events took place as the newspapers reported them, that Captain Bain’s wolf was never caught? The last English wolf then.

***

31 Jan 2011: Amanda writes in with this – ‘there have been some reports of wolf sitings in the uk in recent years: ‘Cannock Chase seems to be a favourite haunt. This report of a wolf from last year. This is a 2009 report of a wolf from Scotland.’ Here we seem to find ourselves in the ABC realm – the large ‘cats’ that are spotted in the British countryside and yet never caught. Thanks Amanda!!