Plato’s Atlantis after Plato January 7, 2011

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient , trackback

Was or wasn’t Atlantis a creation of Plato (obit 347/348 BC)? In antiquity as today – see Beachcombing’s previous ravings – there were competing views with the majority including Poseidonius and Aristotle (or pseudo-Aristotle?) believing it a myth. Aristotle as a student of Plato has particular authority and his opinion reported in Strabo unnerves modern Atlanteans, who will understandably do whatever it takes to defend their continent.

There is only one conspicuous believer from ancient times, but, make no mistake, he is an exciting one. Enter Crantor (obit 275/6 BC) a ‘grandson’ of Plato in academic terms – his teacher Xenocrates had been a student of the Great One: ‘think like a butterfly, pontificate like a bee’.

We know that Crantor had an opinion on Atlantis and that he reported this in his Commentaries on Plato’s work. Unfortunately these Commentaries are lost (another post, another day) and save a miracle, in which the sands of Egypt hiccup up a couple of rolls, they will remain lost.

However, by good fortune Proclus (485 AD), a mule-headed Neo-Platonist (and a Beachcombing demi hero), writing seven hundred years later, quotes Crantor and his view on Atlantis in his own Commentaries.

If you, reader, then want to walk down this particular hall of fairground mirrors Beachcombing will now present Plato’s alleged opinion, written down a generation later by a disciple and then abstracted (or misabstracted?) by Proclus seven centuries afterwards.

Note that an interesting study in translation might be made looking at the way that this paragraph has been manipulated over the years!

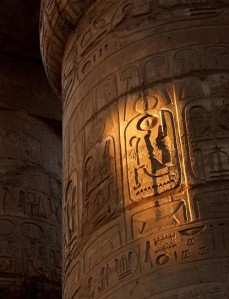

With respect to the whole of this narration about the Atlanteans, some say, that it is straightforward history, which was the opinion of Crantor, the first interpreter of Plato, who says, that Plato was derided by those of his time, as not being the inventor of the Republic, but transcribing what the Egyptians had written on this subject; and that he [Plato?] so far regards what is said by these deriders as to give credit to the Egyptians for this history about the Athenians and Atlanteans, and to believe that the Athenians once lived conformably to this polity. He [who? Crantor? Plato?] adds, that this is testified by the prophets of the Egyptians, who assert that these particulars [what particulars?] are written on pillars which are still preserved.

Crantor’s opinion can be boiled down then to two points. (i) Plato had fun heaped upon him for not being an original thinker but for copying Egyptian thoughts on the subject. (ii) ‘the prophets of the Egyptians’ (who?!?) claim that these records are recorded on pillars.

The first point is interesting and perhaps gives us a blast of polemic from Athens in the generation after Socrates’ death. But it need tell us nothing about Atlantis. It is, after all, merely the view of Plato’s fellow citizens.

The second point though is fascinating. Beachcombing will not suggest, as some have done, that Crantor had been to Egypt and read these pillars and their hieroglyphs or that Crantor had sent someone or that UFOs are somehow involved. Beachcombing is though collecting outrageous interpretations of this sentence if there are any volunteers out there: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

But a generation after Plato’s death – or can this opinion even be ascribed to Plato? – some in Athens were claiming that Plato had ‘source material’.

Of course, this ‘source material’ could be explained in a hundred ways: perhaps even through Proclus’ desire to balance his argument. Is it even possible that the ‘prophets’ had heard of Plato’s ramblings and decided to prove the Greek prophet (Plato) right with some obscure reference from their own land? The Sea People, for example. Proof this that then leaked back to Greece?

Beachcombing hasn’t the slightest idea, but it is worth remembering just how complicated transmission can be when the soggy spaghetti of legend is involved.

Beachcombing has noted before that he suspects that Atlantis is a misinterpreted Egyptian myth with no historical basis rather than a Platonic invention. Still this is nothing more than a suspicion and Beachcombing is not yet senile enough to base an argument on this fragile half sentence of Greek.

Beachcombing will finish with the rest of Proclus’s thoughts on Athens because Beach is a Neo-Platonist at heart.

Others again, say, that this narration is a fable, and a fictitious account of things, which by no means had an existence, but which bring with them an indication of natures which are perpetual, or are generated in the world; not attending to Plato, who exclaims, ‘that the narration is surprising in the extreme, yet is in every respect true’. For that which is in every respect true, is not partly true, and partly not true, nor is it false according to the apparent, but true according to the inward meaning; since a thing of this kind would not be perfectly true.

Beachcombing loves the way that after a while Platonist waffle becomes pleasant white noise. Reading this stuff is like listening to pages turning in a dreamy academic library.

***

9 Jan 2010 Obstacle Course has written in noting that Plato claims, in his own writing, to have gotten his Atlantean information through an ancestor and ultimately through the Athenian lawmaker, Solon. Beachcombing should certainly have stressed this: but what is interesting for Beach is corroborating evidence or pseudo-evidence apparently external to Plato.