Review: War Elephants July 27, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Medieval , trackback

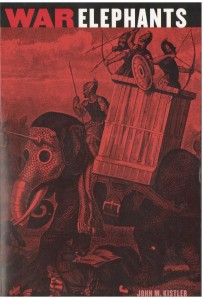

Beachcombing is bringing Elephant Week, ‘the freakish fringe history of the largest land mammal’, to a close with a review of an outstanding recent publication War Elephants by John M. Kistler (Nebraska 2007). In this work the author covers the history of pachyderms on three continents – Africa, Asia and Europe – from the earliest time to the Vietnam War.

Kistler has four characteristics that make him a worthy guide.

First, the author clearly loves elephants: he even has a mahout certificate! Kistler peppers his text with human adjectives like ‘poor’ and ‘courageous’ to describe the fate of his war elephants and gives constant testimony to sympathy between humanity and elephant-kind: be that the Roman crowd booing the slaughter of elephants, Chinese villagers commemorating an elephant that saved them from bandits or the RAF pilots in Burma asking to be excused from killing pachyderms drafted into the Japanese army.

Second, he has an eye for the fabulous details that, as this week Beachcombing has tried to show, collect around elephants. Whether it is the elephants on a train in Russia being calmed down with vodka or the camels dressed to look like elephants or the elephants dressed to look like yaks (!!) the reader will enjoy the ride.

Third, the author is very good at bringing a sense of the scale of elephants home to the reader with numbers and statistics: quoted or calculated. So an elephant can sprint fifteen miles an hour at an enemy – terrifying when you think about it. Eight elephants are an ile and 16 an elephantarchia. An elephant can swim 50 kilometres in the sea (Beachcombing still has problems believing this). 500 elephants would need 110 tons of fodder a day. And the 200 elephants that Alexander kept near him would have produced about 25 tons of dung in a day.

Then fourth, and finally, the author has an engaging style. There are frequent exclamation marks and striking images including a comparison of male elephants in a rage to Star Trek’s Dr Spock: Beachcombing seemed to see the face of Leonard Nimoy superimposed on every image of elephants that followed! It might even be said that the book has something of a bloggish feel about it. For the harrumphing sorts that complain about split infinitives and the Oxford comma that can only be a bad thing. Beachcombing relaxed and read it in bed between siestas: rather than at the table quivering with a pencil. He’s consequently grateful.

In going through this book, the reader will skim text-book history from the Fertile Crescent, to Alexander, to the Punic Wars and the rise of Rome: is the history of pachyderms the history of man?

The book is very successful, in fact, in telling that story up until the time of the end of the Roman Principate. But then as it widens outside the classical world order breaks down and the book becomes a collage. In the author’s defence it must be said that this is also true though of the traditional narrative of western history!

A linked problem can be seen in the chronological spread of the book. From pp. 1-166 we go up to the death of Julius Caesar. From p. 167-234 we take the story up to the twentieth century, while also taking in new parts of Asia including the entire sub-continent, China, the Mongols and Vietnam! There is some disproportion here.

Naturally, certain historical details are suspect. Beachcombing would disagree, as he has stated elsewhere, with the idea that Caesar brought an elephant to Britain. Not least because Caesar would never have been able to resist mentioning the elephant in his Gallic Wars: Caesar lived for things that he could boast about at dinner parties and this would have been one of them. However, Beachcombing has to say that perhaps he, not the author, is in a minority on the British elephant question.

The bibliography is immense. Summarising important elephant books (p. xiii) the author refers to the ‘extremely rare’ Histoire Militaire des Elephants by Colonel Armandi (1843): this book is now on google books, though Beachcombing has not checked to see how badly it has been mauled by those digital clowns. The author does not refer to Konstantin Nossov’s War Elephants (2008) for the very understandable reason that it was published a year later than his work: it is a very brief (pp. 47), richly illustrated and well-structured book. It is curious that the author does not refer to Charles Holder’s The ivory king: a popular history of the elephant and its allies (1902) with its chapters on war elephants and Beachcombing found no reference to Halliburton’s Seven League Boots (repr 2001) with Halliburton’s attempt (that ends in tears) to create Hannibal’s trip over the Alps. It might not be particularly serious but it is immense fun.

Beachcombing will finish with his favourite elephant anecdote of all, noted by the author on pp. 159-160. Plutarch tells us that Pompey, one of many unpleasant Romans of which history has left us notice, wanted to be brought through Rome in triumph on a chariot dragged by four elephants. So far, so predictable. However, as the vain glorious procession came up to the city gate it became clear that the elephants were not able to fit through the city gate and pompous Pompey has to abandon his chariot in full view of the city, get down and walk.

It couldn’t have happened to a nicer person…

Beachcombing is always on the look out for good elephant books. drbeachcombingATyahooDOTcom