Mongol elephants in America? July 22, 2010

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackback For the second article of Elephant Week Beachcombing thought that he would introduce one of his favourite early nineteenth-century books.

For the second article of Elephant Week Beachcombing thought that he would introduce one of his favourite early nineteenth-century books.

Just let the title wash over you…

John Ranking’s Historical researches on the conquest of Peru, Mexico, Bogota, Natchez, and Talomeco in the thirteenth century by the Mongols, accompanied with elephants: and the local agreement of history and tradition with the remains of elephants and mastodontes found in the New World (London 1827).

And you thought that Asians arrived in America only in the sixteenth century and that there were no elephants in the new world in historical times?

But this book is so much better than even the title suggests. Indeed, there are many wonderful moments including the search for carnivorous North American mammoths (not extinct at time of publication) and the suggestion that an animal on an Iron Age British-Celtic coin is a tapir…

Told quickly Ranking’s central theory goes as follows. In 1274 a Mongol invasion of Japan was repulsed by an enormous storm: this is a matter of record. Ranking though argues that some of these ships (with Mongols and elephants) ended up in the New World. His evidence? The following passage from ‘El Inca’ Garcillasso de la Vega’s writings.

‘I shall relate,’ says Garcillasso de la Vega [obit 1616, pictured above], ‘what Pedro de Cieza de Leon [obit 1554] told me that he had heard in the province where the giants arrived. They affirm, said he, in all Peru, that certain giants came ashore on this coast, at the Cape, now called St. Helen’s, which is near the town of Puerto Viejo. Those who have preserved this tradition from father to son, say, that these giants came by sea, in a kind of rush boats, made like large barks; that they were so enormously tall, that from the knee downward, they were as high as common men; that they had long hair, which hung loose upon their shoulders; that their eyes were as large as plates, and that other parts of their bodies were big in proportion; that they had no beard, that some went naked, others were covered with the skins of wild beasts and that they had no women with them. After having landed at the Cape, they established themselves at a spot pointed out to them by the inhabitants, and dug very deep wells through the rock, which to this day supply excellent water. These giants lived by rapine, and desolated the whole country; they say, that they were such gluttons, that one would eat as much meat as fifty of the native inhabitants; and that for a part of their nourishment they caught a quantity of fish with nets. They massacred the men of the neighbouring parts without mercy, and killed the women by their brutal violations. The wretched Indians often tried to devise some means to rid themselves of these troublesome visitors, but they never had either sufficient force or courage to attack them.*Secure from all apprehension, these new monsters thus tyrannized for a long while, committing the most infamous enormities. Divine justice sent fire from heaven with a great noise, and an angel armed with a flaming sword, by whom they were destroyed at one blow. To serve as an eternal monument of the vengeance of God, their bones and skulls were not consumed by the fire, but are found at the very place, of an enormous size. I have heard Spaniards say, that they have seen bits of their teeth, by which they judged that a tooth weighed more than half a pound. As for the rest it is not known from what place they came, nor by what route they arrived. I learned this year [1550, aged 11!], when I was at the Ville des Rois [Lima], that during the viceroyalty of Don Antony Mendoza, in New Spain, bones had been found there of a still greater size than the above mentioned. I also heard that, in the city of Mexico, some had been found in an old sepulchre; and also in another place in the same kingdom. We may infer from this, that these giants have existed, and that what authors have written about them is not fabulous. Another wonderful thing is, that at Cape St Helen’s there are springs of liquid pitch, which are fit for the purposes of ship-building.’

Beachcombing is sure that the reader will have noticed the barely hidden references to Mongols disembarking from their ships on elephants. They certainly did not escape Ranking who wrote in a note (relative to the asterisk in the text): ‘The elephants would, no doubt, be defended by their usual armour on such an extraordinary occasion, and the space for the eyes would appear monstrous. The remark about the beards, &c. (many of the Mongols have no beards…) shows, that the man and the elephant were considered as one person.’

Now, of course, storms do bring sea travellers to places that they would not normally dream of going: the Vikings, for example, went beyond Iceland with the help of such tempests. But Beachcombing has been able to find no proof that there were any elephants in the Mongol invasion ships bound for Japan. Not surprising given the appalling problems that Hannibal had in getting his few elephants across the Rhone: never mind poor Pyrrhus bringing elephants over the Adriatic.

Beachcombing feels bound to note too that legends of invaders coming from the sea are common to many maritime cultures: the sea brings seagulls and death and makes those living beside it itchy with worry. (Beachcombing once spent three terrible months in a Breton seaport and the noise and the smell filled his dreams.) In this light, note how the story Vega reports seems to involve initial cooperation between invaders and the locals, ‘a spot pointed out to them by the inhabitants’, a classic legendary invasion motif.

There was perhaps an attempt here on the part of a pre-Columbian population, taken up enthusiastically by the Spanish, to explain large bone remains that they had found. Fossils often excite legends because they demand explanations: indeed, much of Ranking’s book could be seen as a continuation in that tradition. (For fossils and legends Beachcombing would recommend Peter Dodson and Adrienne Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times). Then the pitch springs may be the origin of the legend of the angel of death?

Ranking though was already on his jolly up the Mountains of Madness and nothing was going to hold him back. There follow another three hundred and fifty pages of pure, magical delirium.

Beachcombing recommends this book in the highest possible terms not least because Google has actually managed to digitalise it getting almost all the pages right and not smearing the print too much. A rare achievement.

He is also very interested, should any reader be able to help him, in other ‘evidence’ for elephants in pre-Columbian America especially in pre-Columbian objets d’art – note that the reader does not have to believe the ‘evidence’! drbeachcombingATyahooDOTcom

Elephant Week is dedicated to Beachcombing’s dear friend and notable elephant lover Raoul who helped the Beachcombings put up a curtain rail a few days ago.

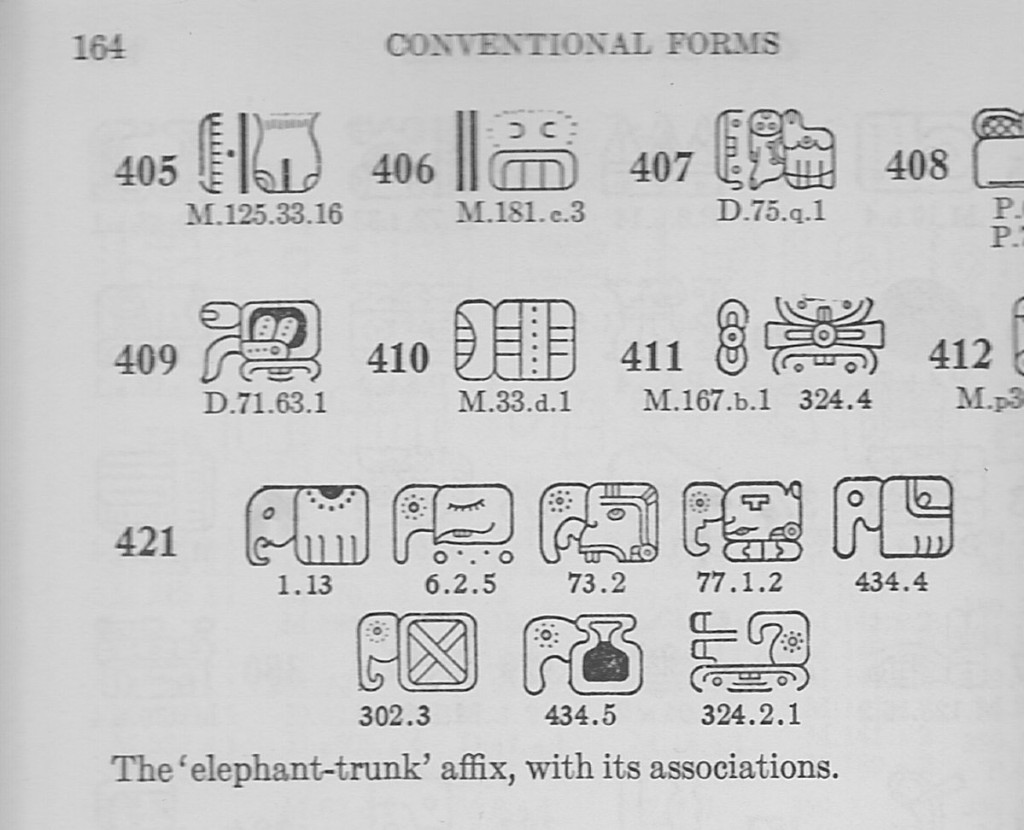

21 July 2015: Chris S writes in ‘The following transcription of regards Italian medals with elephants embossed on the obverse being found in North America. They don’t have an anomalistic origin but their path is interesting enough, illustrating the conquest of North America. Mentioned in the text is the Elephant Mound in Wisconsin. Also the elephant/mastodon pipes. Of interest is the tradition of elephants in Mormon lore. Mayan glyphs may have represented elephants too. See attached. A ceramic elephant from an Olmec tomb. Attached as well is a possible elephant sculpture at a Mayan site.

By N.H. WINCHELL

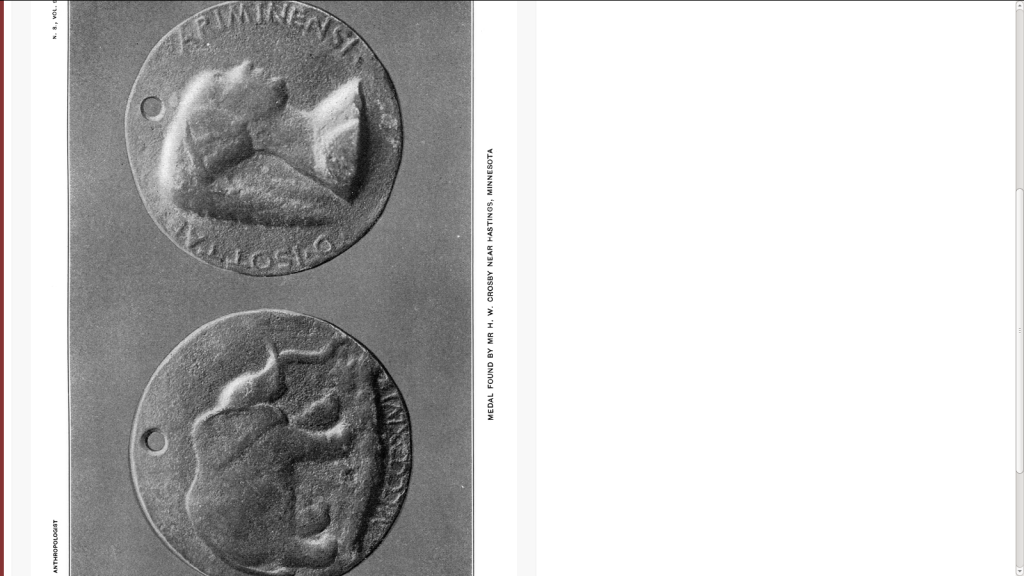

In one of the archaeological volumes of the late J.V. Brower he has published an account of the discovery of a remarkable bronze medal bearing date 1446. It was found by Mr. Howard W. Crosby in an old Indian trail in “Pine cooley,” near Hastings, Minnesota. Mr. Brower introduced a plate showing both sides of the medal, [[1]] and his remarks lad to the belief that it was of Indian origin and is to be classed with other discoveries that have been reported showing that the Indians had knowledge of the elephant. It is well known to archaeologists that pipes of catlinite shaped like the elephant have been discovered in Iowa, also that a so-called “elephant mound” in Wisconsin has been much depated since it is situated in the region of the effigy mounds of the Northwest. Later some fragments of elephants’ (or mastodons’) tusks have been exhumed from a mound in Wisconsin by a representative (Norris) of the Bureau of American Ethnology.

[[1]] Minnesota, pl. IX.

Since the publication of Mr. Brower’s volume two other bronze medals of identical size and figure have been discovered — one at Grand Forks, North Dakota, the other, as reported, at St. Cloud, Minnesota.

The coexistence of man and the mastodon, or mammoth, in America, as in Europe has advanced now beyond the stage of presumption, and has been so well verified that it can hardly be excluded from the realm of science. [[2]] Still it is necessary to exercise care in the use of facts brought to light that seem to bear on this question.

[[2]] Prof. W.B. Scott in Scribner’s Magazine for April, 1887, has exhaustively reviewed the evidence of the late existence of the elephant in America, and has concluded that not many centuries ago the elephant was an important elephant in American life.

I have seen Mr. Crosby’s and Mr. Kennedy’s medals and can vouch for their genuineness. They were certainly beyond the skill of the Minnesota aborigines, both in the metallic alloy of which they are composed and in the mechanical execution of the embossing, to say nothing of the Roman characters and the correct Latin in which they are inscried. They can have therefore no relation to aboriginal elephant pipes or to elephant mounds, and hence, though they were molded prior to the discovery by Columbus, they cannot be accepted as evidence that the Indians were familiar with the great pachyderm.

In searching for some explanation of the origin of these medals, and of their occurrence in America amongst the Indians, I have been aided by Judge George B. Young, of St. Paul, and by Prof. Igino Sapino, director of the National Museum, Bargello, Florence, Italy. I have been permitted to use here a copy of a letter written by Judge Young to Mr. H.P. Upham of the Minnesota Historical Society, published in the Hastings Gazette of December 17, 1904, which shows the Italian origin of these medals.

ST PAUL, Nov. 15, 1904

DEAR UPHAM:

The medal which you showed me this morning, and which was recently dug up at Grand Forks, was undoubtedly issued in honor of the Lady Isotta of Rimini. Such is the plain meaning of the inscription on the obverse of the medal, namely, “D. Isottae Ariminensi,” the letter D. doubtless standing for Dominae. The date on the reverse 1446, in Roman numerals, is no doubt the date on which the medal was struck.

Sigismondo Malatesta, Lord of Rimini, although already married, fell madly in love with the Lady Isotta, who was celebrated for her beauty, intellect, and culture, and continued until the end of his life the object of his adoration. She became his mistress and bore him several children in the lifetime of his first and of his second wife; and when he became a second time a widower she became his wife.

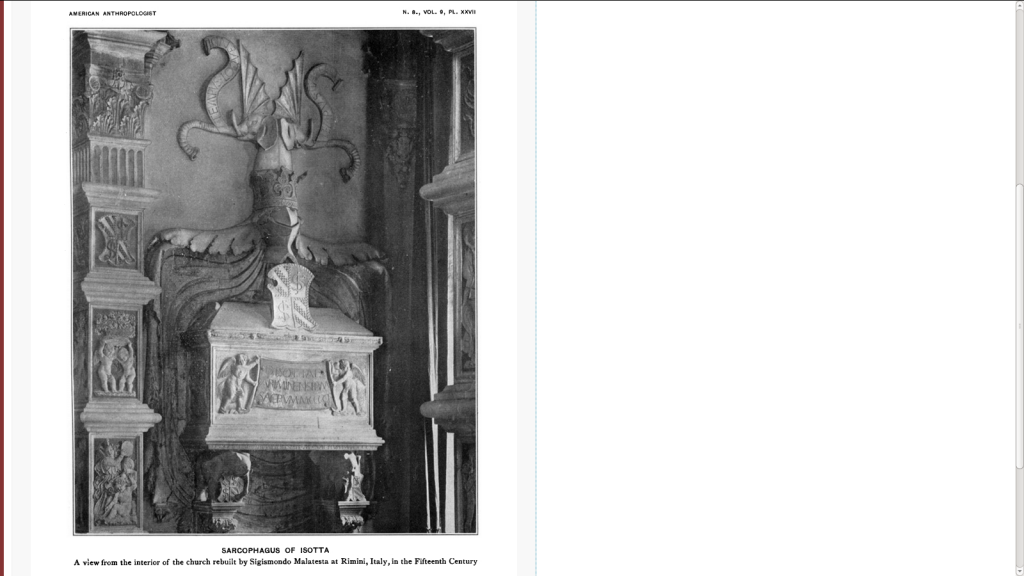

In the year 1446, Sigismondo Malatesta began the construction of the remarkable church of San Francesco at Rimini. In one of the chapels of that remarkable church there still remains the splendid and fantastic tomb erected to Isotta in her lifetime. The urn of her sarcophagus is supported by two elephants, and bears the inscription, “D. Isottae Ariminense, B.M. sacrum MCCCCL.”

The D. has been interpreted by some as Divae, goddess, or divine, and B.M. as Beatae Memoriae (of Blessed Memory); others, unwilling to credit such impiety, hold that B.M. is Bonae Memoriae (of Good Memory). However this may be, the D. may well be interpreted as standing for Dominae, both on the urn and on the medal. It will be noticed that the elephant is common to the tomb and to the medal.

Sigismondo Malatesta died in 1468; Isotta in 1470.

Signed (JUDGE GEO. B. YOUNG)

TO H.P. UPHAM, ESQ.

The accompanying plate XXVI illustrates the medal of Mr. Crosby. Plate XXVII shows the sarcophagus of Isotta mentioned by Judge Young, from a photograph procured in Italy by Mr. E.A. Whiford and furnished by Mr. Crosby. The church dates from the thirteenth century, but its present condition is due to a reconstruction by Malatesta in the fifteenth century in honor of Isotta.

A letter from Professor Sapino as translated by M. Giuliana of St. Paul is as follows:

FLORENCE, ITALY, Jan. 10, 1907.

DEAR SIR:

That medal which you wrote to me about is the one made by Mattei di Pasti (born 142-, died 1490?). He was an architect and painter. His name was Pandolfo Malatesta Signore di Rimini. He was working as an architect with Leon Battista Alberti at this time on the construction of the St. Francis temple at Rimini, and made these medals for Signore Pandolfo Malatesta and for Lady Isotta Atti, and the medal was presented to her in 1446; but I am unable to tell when the medal was brought to America. If it is important to know if the medal is of any value and to trace its history you can see any of the following:

Armand: I’medaglioni della Rinascenza, Paris 1883-1887.

Sapino: Catalogo delle medaglie nel Tempio nazionale di Firenze

Talregg: Italian Medals

IGINO SAPINO

Director Nat. Museum, Bargello, Florence, Italy.

I have not been able to consult any of the works referred to by Professor Sapino, but the pleasant little volume of Mrs. E. Augusta King, entitled Italian Highways (1895), gives an account of a visit to Rimini, in which she describes this temple, or church, of the Malatestas, and dwells on the numerous signs of dedication to Isotta. He “elevated her to the rank of a divinity, and placed all over the church, as if it were some Christian monogram, the initials of her own name and his own — I.S. … and itroduced into the sculptured ornament of hte cathedral, inside and outside, his badge of an elephant and hers of a rose, together with his coat of arms, and his portrait, and their monogram.”[[1]]

The foregoing is sufficient to prove the medals be of Italian origin, and it remains only to call attention to their possible source. It is well known that one of the most efficient and trusted of the companions of Las Salle was the Italian Chevalier Henry de Tonty, who was with him at Fort Crevecoeur on the Illinois river, whence Hennepin and Michel Accault departed for the purpose of exploring, under La Salle’s direction, the upper waters of the Mississippi. This was in March, 1680. In La Salle’s letter describing this expedition he states that Accault was furnished with “about a ten thousand pounds of goods, such as are most valued in those regions.” This party was captured and robbed by a band of Sioux Indians in the Vicinity of Lake Pepin, and were conducted to M ille Lacs, in Mille Lacs county, Minnesota. These articles usually taken on such expeditions were such as would propitiate the natives — hatchets, knives, tobacco, gaudy cloths and beads, and such articles of personal adornment as rings, bracelets, and medals. There is no mention of medals in the outfit of Accault. It seems probable, however, that he had a number of the Isotta medals, and that they were supplied by Tonty, who was probably not alone a companion of La Salle, but, judging from his independent action and authority, was also in some measure a partner interested in the expected emoluments of La Salle’s discoveries.

From Mille Lacs the medals could easily have been scattered anywhere in the northwestern region within the area occupied by the Sioux at that time. None has been found, as yet, within the area dominated then by the Ojibwa.

ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA,

April 3, 1907

[[1]] SEE ALSO A LATE PUBLICATION: “Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, Lord of Rimini. A Study of a XV Century Italian Despot.” By Edward Hutton. New York, E.P. Dutton and Co. 1906.