William, the Fairies and the Bath June 1, 2022

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback*This is the subject of Chris and my most recent Boggart and Banshee podcast*

**For the source file; and for other Puca books and pamphlets**

William Butterfield’s run in with the fairies at Ilkley is one of the best-known encounters in British supernatural folklore. An account appeared in the first number of Folk-lore Record in 1878 and from there it seeped down into the works of many fairyists including Katharine Briggs, Richard Sugg, Janet Bord, Kai Roberts and John Kruse. The present author has even warbled on about it from time to time and this month’s Boggart and Banshee podcast explores William’s unlikely adventures.

The Encounter

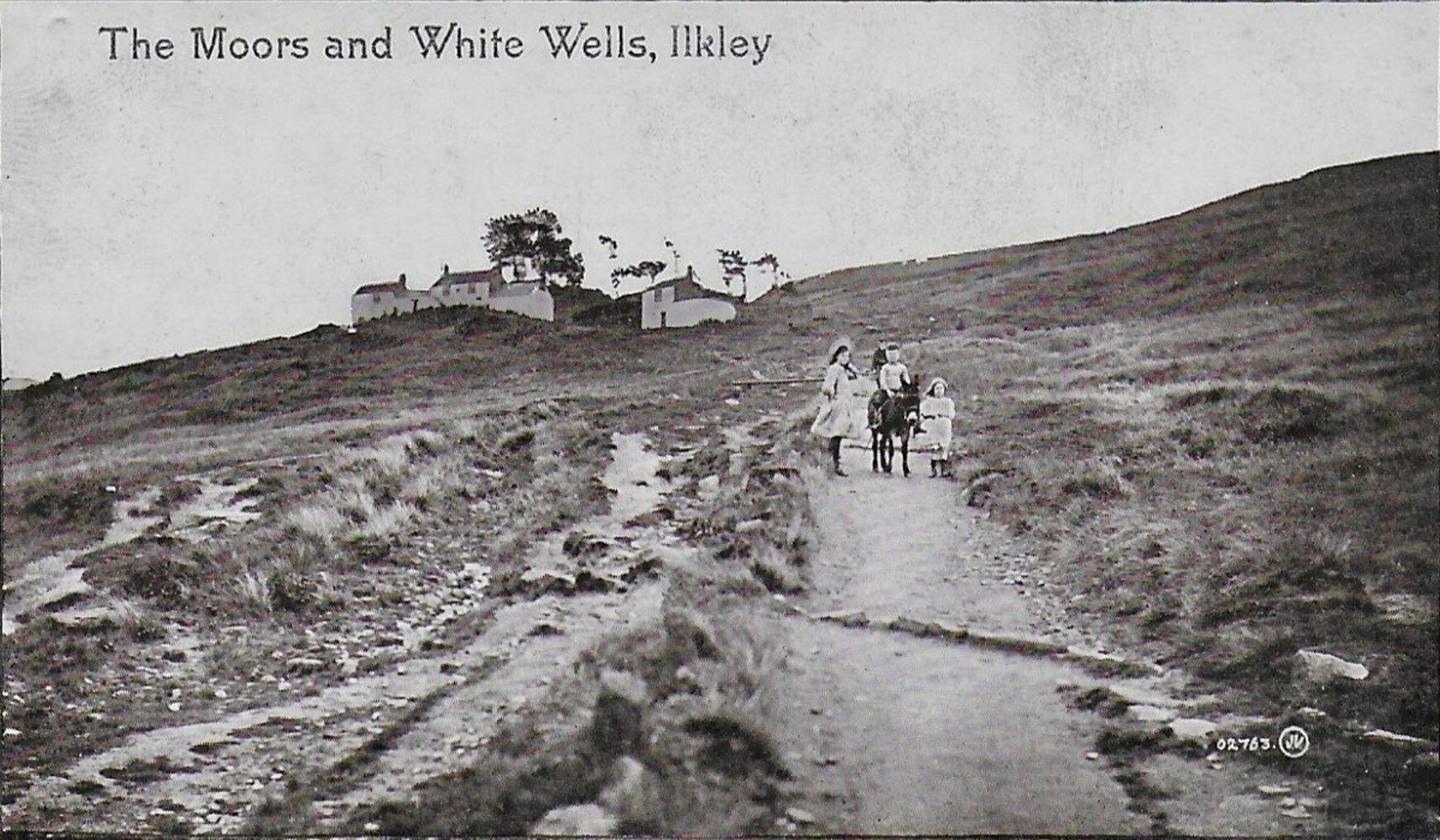

So what happened? Very early on the morning of 24 June in 1819, 1820 or 1821 (or thereabouts) a man in his forties called William Butterfield walked up the valley side at Ilkley. He was going to the White Wells, of which he had recently become the proprietor. It is tedious but let’s get this out of the way: he did not have a reputation as a drunk or a liar.

Butterfield arrived (the timing is arguably important) just before dawn on Midsummer’s Night and came to the door of the baths. The door in question led to a walled open space and the baths beyond. Necessary background – the baths were some cold springs where jaded Ilkley folk could come and refresh themselves by bathing and drinking. Increasingly the ‘baths’ at Ilkley would bring in health tourists, but that is another story.

Butterfield took out his key and tried to turn it in the lock of a door, but the door would not open. He played with the key some more and made out laughing and scrambling sounds on the other side. With some effort – he felt that he was pushing against something – he finally managed to get the door open. What a sight confronted him!

All over the well, skimming on its surface like water-spiders, or dipping into it as if they were taking a bath, was a swarm of little people, the biggest of them not above eighteen inches high; yet they seemed perfect human beings. They bathed with all their clothes on; and Butterfield noticed that they were dressed from head to foot in green.

The fairies skedaddled as soon as William Butterfield came on the scene. In fact, they ‘bounded over the eight-foot wall like so many india-rubber balls’ or went ‘bounding over the walls like squirrels’. Butterfield was understandably amazed but he, even in his state of shock, was able to walk past the house to see the stirring of the bracken as ‘if a troop of hares or rabbits, or some such small animals, were scampering through it’. It is a lovely detail.

The Sources

Butterfield seems to have been born in 1775. The sighting took place c. 1820, perhaps just five years after Waterloo. Butterfield never, that we know of, wrote an account of his brush with the fairies. But he did describe the event to his young friend John Dobson, probably c. 1840. Dobson did not write an account either. But we have two authors who talked to John Dobson about William and the fairies and they wrote their own versions of what happened.

The first of these was Dinah Craik, a Staffordshire novelist: she published a magazine piece in 1870. The second was Charles Smith, a Yorkshire folklorist, who published his version in, as noted above, Folk-lore Record in 1878. The two accounts are remarkably similar, perhaps too similar… My impression is that Craik wrote a rather ‘precious’ and literary version and that Charles Smith (who certainly knew Dobson) used that account as the basis of the 1878 version. He cut away and corrected (as he saw it) some details.

The truth is that whatever the exact genealogy of our two accounts these sources are disappointing. We have the story not at first-, not at second-, but at third-hand: if Smith copied Craik his version is at fourth-hand. Who knows how close the story is to what actually happened to William Butterfield on that summer morning a half-century before?

(For an edition of all the sources)

Explanations

Various authorities have tried to make sense of William Butterfield’s fairy happenings with the imperfect versions that have come down to us. Is it possible, for instance, that Butterfield actually saw some kind of animal life and a little groggy after getting up early in the morning and walking up a steep hill, misinterpreted what he saw?

Even if we question Butterfield’s eyesight* or judgement, it is difficult to think of an animal that comes close to this in the UK. We need a creature that: i) gathers together in groups; ii) is green; iii) can run up or bounce over an eight-foot wall; iv) makes a scrabbling and laughing sound; and is v) from six inches to eighteen inches long. The list is very short.

My preferred zoological option would be… rats. Perhaps some crumbs had been left next to the side of the baths by a bather. The rats had come in over the walls and rats’ scrabbling and cheeping was what Butterfield heard. Certainly rats could skimp over an eight-foot vertical surface at speed. As to the colour green… I’m tempted to bring in chloris as some of those who explain the Green Children of Woolpit have done. But, no, let’s move on.

Gordon Holmes, in a very rare and enjoyably strange booklet, Fairies on Ilkley Moor: The Evidence (finding fairies in photographs and videos from the area) suggests that Butterfield actually encountered lizards. At least, here we can account for the colour green. Lizards do sometimes gather together. But this was pre-dawn: lizards come out to eat or sun themselves. The size and noise (at least the ‘laughing’) is wrong too.

So did Butterfield see fairies? John Dobson had as many questions as I do, but he summed up the situation rather well: ‘when an honest man, whose word you have no reason to doubt, looks you in the face and tells you he has really seen so and so, it’s rather hard to look him in the face back again and tell him he hasn’t.’ This is particularly the case if the best you can do as an alternative are viridescent rats or laughing, sun-averse lizards.

Folklore

When I have looked at this case before I have looked at it in terms of William Butterfield’s experience. This time, reading other Ilkley sources, and trying to get a better sense of the landscape, I wanted to look at the experience in terms of local folklore. This is not, I admit, anything like an explanation, but it does give context.

The first point is the setting. The White Wells bubble up to the surface on the edge of Ilkley Moor. The moor was demonstrably associated with fairies. A ten-minute walk to the east there is the Fairies’ Kirk with a great overhang where the Fairies’ House is to be found. Craik tells us that you had to go there in the very early morning if you want to see the fairies; an interesting point given the timing of Butterfield’s encounter.

One source from the 1860s claims that ‘the space between the foot of the West Rock and the Old Wells [the baths], was a favourite resort of’ the fairies: this would be the area immediately beyond the baths, moving on to the bits of open moor. William Butterfield then was in the right place to run into trouble.

What about the baths themselves? The White Wells, aka the Old Wells were also known as the ‘Roman’ baths by the late nineteenth century. Now as it happens it is unlikely that these were ever part of a Roman bath-house. As Ian Rotherham put it in his Roman Baths in Britain: ‘Quite when the Roman claim developed seems shrouded in mystery. As a major Roman garrison town, Ilkley certainly had a Roman bathhouse.’ But the ‘White Wells seems an unlikely candidate for the site of the baths…’

Over parts of England, though, fairies and Romans had been associated with each other. For instance, Roman coins that were dug up were called, in places, ‘fairy money’. In fact, British folklore often paid past peoples the compliment of calling them ‘fairies’: be they Georgians with their ‘fairy pipes’ or Palaeolithic hunters leaving their ‘elf shots’ behind them. If locals thought of the wells as having a Roman origin, it would have been still easier to tie fairies in with the natural springs there. Alternatively, the wells were called ‘Roman’ because they were connected with fairies.

Then there are Fairy Wells, generally. Up and down Britain there are perhaps two score places called ‘Fairy Well’ or Fairy Spring’: water sources associated in language with the fairies. There are then about as many other instances where the word ‘fairy’ does not appear in the name, but where ‘fairies’ are coupled in legend with a water source. This is particularly true of wells on the edge or a little way from human settlements. It is almost as if the well is a resource shared by humans and the wilderness-dwelling fairies, a meeting point, if you like.

All this is to say that a fairy-believing woman might, say, in the early nineteenth-century, have been, surprised to walk in on a group of bathing fairies in the early morning at the White Wells. But she could hardly complain, coming at the very end of the most fairy night of the year, at a ‘Roman’ well, next to a fairy-infested moor!

As to William Butterfield I’m more pessimistic than I once was about the details in the account that has come down to us. This is not because I don’t trust William Butterfield. It is because the chatter comes to us at ‘third-hand’; perhaps this is another way of saying I don’t trust ‘people’. But we can, I think, be certain of one thing. Local fairylore has eaten through this tale, like woodworms through an unvarnished oak beam. How much fairylore was built into Butterfield’s experience on that extraordinary morning two hundred years ago? How much arrived in the telling? It is a nice question.

drbeachcombing AT gmail DOT com

*Predawn behind an eight-foot wall, remember…