Ghosts and Fairies Attacking Railways June 17, 2020

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackRailways and Bogies

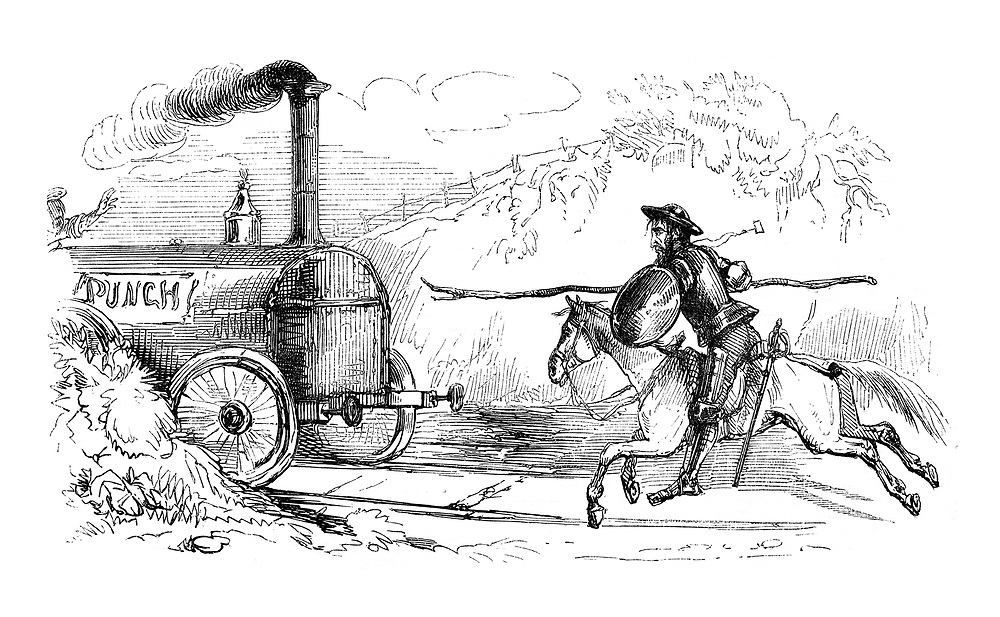

One thing that united the Victorian supernatural world was a passionate loathing for railways. We have, in the nineteenth century, report after report of fairies and their ghostly cousins disappearing once trains arrived in a given valley. Fairies ‘have fled before the steam whistle from many a sylvan scene’ as one Scottish journalist trilled it, and comments like this could be multiplied dozens of times over from the 1840s through to the Second World War. But what – bear with me here – if occasionally, the local bogies fought back against the tedious march of modernity?

At the time of the construction of the Lancaster and Carlisle railway, something was said of the ‘fairies pulling down the big bridge at Shap,’ where the work perhaps did not get on very expeditiously; but, as far as I am aware, it may have been an unauthentic report (Sullivan 1857, 138).

I’ve treasured this reference for some years as I like the idea of Cumbrian fairies riding Cherokee-style down from the hills around Shap to wreak havoc on the line-layers. But the ‘unauthentic report’ made me reluctant to use it – though quite what ‘unathentic’ means here I’m, not sure… However, I’ve just published the folklore ‘remains’ of a nineteenth-century Manchester writer, John Higson (1825-1871) [South Manchester Supernatural: The Ghosts, Fairies, Boggarts and Superstitions of Victorian Gorton, Lees, Newton and Saddleworth cheaper bought directly from me than on Amazon, ahem] and came across a similar reference.

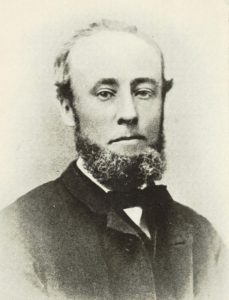

John Higson

Higson was – some quick background – one of those incredible self-taught Victorian writers. He emerged out of an illiterate family in what was then the village of Gorton and that is now carparks and tarmac, with the odd token tree, in south Manchester. He wrote about local folklore in hundreds of newspaper articles and two books: The Gorton Historical Recorder, (Droylsden: Privately printed, 1852?) and Historical and Descriptive Notices of Droylsden: Past and Present (Manchester: Beresford & Souther, 1859). He also had a full time job and seven kids, but somehow, besides writing and working and fathering he found time to go walking.

This leads us to one of his jaunts, reported in a newspaper article in 1867, in Derbyshire where he visited the home of a ghostly psychopath by the name of Dicky. Dicky, for non Britons, is one of the most famous northern English bogies. He or perhaps she (heck, I’m going to proceed with ‘it’) was a skull that was resident at Tunstead Farm just outside Chapel-Le-Frith. Dicky got very irritated whenever its skull was moved: cue classic poltergeist activity on the property. Now there are lots of screaming skulls in England (there are, I think, five in the north-west alone), but as we shall see, Dicky was unusually ambitious.

Dicky and the Trains

Higson’s writing on Dicky is useful because: (i) it is relatively early in terms of the Dicky legend; and (ii) he knew people in the Chapel-en-Frith area. He also provides a report which starts to make fairy attacks at Shap more credible.

We were shown where the railway embankment had been formed with the greatest difficulty, from the supposed enmity of Dicky, who, it was believed, was opposed to the modern system of travelling and traffic. Again and again the embankment slipped, and the highway from Combs to Chapel-en-le-Frith had to be diverted some distance easterly, as the contractors could not obtain a solid foundation for the bridge, which was to carry it under the line (Higson 2020, 73).

Higson was one of those who was of the devil’s party but didn’t know it. He enjoys the legend then decapitates it with a neat mid Victorian blade flick.

Of course the real truth was the nature of the soil, which consisted of clay resting on sand, a very unfit foundation for any structure.

This story was clearly, to use a word employed for Shap, ‘authentic’ in that dialect poet Samuel Laycock published in 1870 a poem about Dicky’s devilry.

Neaw, Dickie, be quiet wi’ thee,lad,

An ‘let navvies an’ railways a ‘be;

Mon tha shouldn’t do soa, its to bad,

What harm are they doin’ to thee? (I owe this reference to our friends at Lud’s Church)

So what I’m now wondering is whether there are any other supernatural attacks on railways out there?

I am terrified to say this for the first time in my blogging career… But the comments are open below. Please God preserve us from Chinese hackers, American diet companies, penile growth pills and garden-green sociopaths… Or, what the hell, drbeachcombing AT gmail DOT com

PS thanks for everyone who wrote welcoming me back!

For more on Pwca Ghost, Witch and Fairy Pamphlets

Bibliography

Higson, John South Manchester Supernatural: The Ghosts, Fairies, Boggarts and Superstitions of Victorian Gorton, Lees, Newton and Saddleworth (NP: Pwca Ghost, Witch and Fairy Pamphlet series, 2020)

Sullivan, J[eremiah] Cumberland & Westmorland, ancient and modern; the people, dialect, superstitions and customs (London: Whittaker and Co, 1857)