Children and Stories and School February 3, 2018

Author: Beach Combing | in : Actualite , trackbackChildren devour stories… Announce to three kids in bed, just before lights out, that you will tell the tale about ‘naughty Uncle John and the security guard’, or ‘how Daddy went to fox land’, or the one about the ‘biggest fish in Little Snoring’ and absolute silence will reign. The children will listen, crucially ask questions and then recount the story back to you in incredible detail for days to come.

I was reminded of this while recently going on a walk with my middle daughter, a seven-year old. For an hour and a half she told me Biblical stories that she had learnt in religious class at school. Not that nonsense in the New Testament about healing and turning cheeks, but the real narrative gold in the Old Testament: hairy arms, angels with swords, brothers who would sell you into slavery… Even Lucifer (apparently a liar and her favourite) had a decent showing.

For father it was a, rather, tedious walk, but Little Miss B was clearly in ecstasy explaining the events of Jewish prehistory to her ageing pater. These stories mattered a great deal to his little girl. Indeed, when asked which is her favourite class, Little Miss B, without hesitation responds ‘religion’ and this is the kid who wants to grow up to become a roller-blade waitress (really). She and her sisters constantly use analogy in relation to the stories they learn: ‘It’s like when…’ is a frequent refrain.

The Italian education system is, particularly at elementary level, among the finest in the world. But it is striking that my three children actually only rarely return home telling stories. Middle Little Miss B is the only one who goes to the optional religion class: long story, to do with form-filling and a charismatic teacher. Beach has been struck, in fact, by how few tales infants get to listen to at school, in most countries under his purview.

The obvious source would be the history classes that begin at seven in Italy: but these seem all to be about the social hierarchy in Ancient Egypt and other heart-breaking missed opportunities. Religious studies takes the unusual form of stories from the Old Testament, because, as an optional class, it is run by the diocese (even in a state institution) as a kind of Sunday School lesson.

Thinking back to my education in the 1970s and 1980s in the UK my main source of stories was ‘assembly’. Every morning (or most mornings?) the school would gather together, sing a few songs, and then the head would give what was effectively a sermon: a little tale that told us how to be better citizens. I can’t remember how often these took place, but I can still, decades later, remember many of the stories in detail. They have proved, at the risk of sounding portentous, resources.

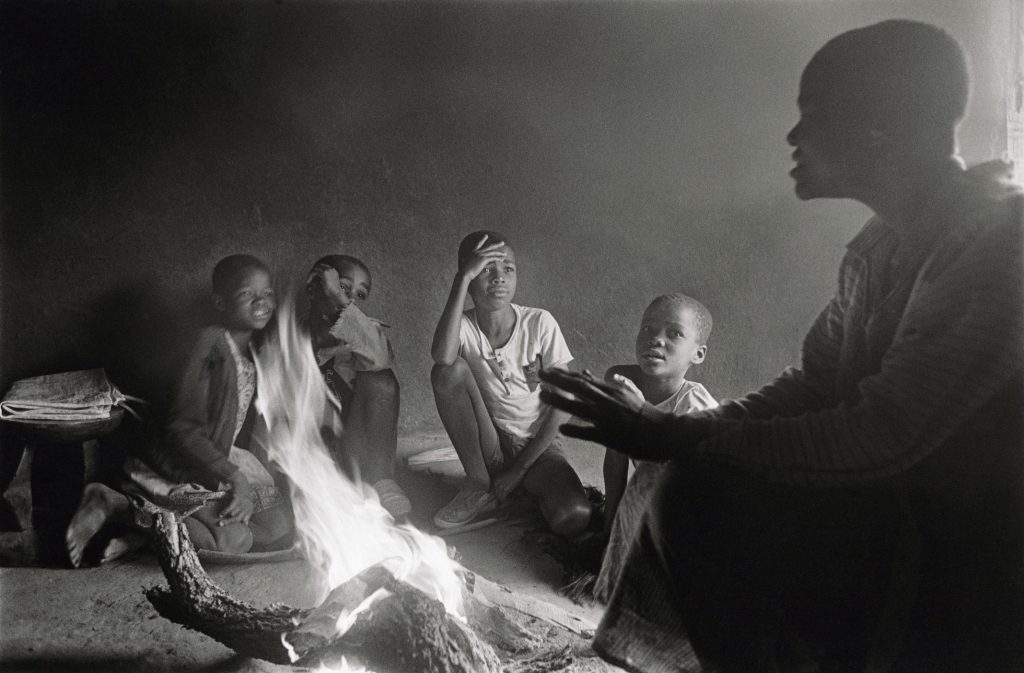

Children have a thirst for tales, so why don’t we give them what we want? The two main sources for twenty-first century kids are certainly books read by parents, and cartoons on Youtube: relatively few children get to hear tales from those around them, particularly not on a regular basis. Why can’t we include stories in education itself? Beach would beg for the introduction of a Myth and Legend Class from five to ten, where kids go through different cycles and pantheons every month. There would be no tests, no books and no cartoons: just an adult talking and twenty spell-bound infants.

Other thoughts on kids and storytelling: drbeachcombing AT gmail DOT com

Chris S. 28 Feb 2018, Stories are important for humans. Period. The best podcasts are the ones which tell stories, rather than provide data and facts. The latter are boring and dry, while the former are relatable and engage the listener with learning. If someone’s just an audience, and not engaged in learning, then there’s something wrong and someone’s time is being wasted. Taking an anomalistic bent, greyfaces and skeptics who are just about debunking something. For example, Neil Tyson saying “There’s no sound in a vacuum, therefore Star Wars is anti-science” or “The earth is flat” doesn’t capture anyone’s imagination. If Neil Tyson told a story, imagined a fable, or related an encounter he had with someone holding beliefs contrary to his own, then he’d be interesting. Instead, Neil Tyson’s just an encyclopedia with legs and a mouth. And who needs Neil Tyson when we have Wikipedia or, like us old timers, a set of encyclopedias. It all comes down to “hearts and minds”. Minds are sessile, unless the heart is aroused and fills the brain with more hot blood. Many instructors assume there’s one “best” kind of student and all students should adhere to that ideal, rather than taking extra time to give special attention or be a mentor. With the advent of the industrial age, education remains industrialized, hopefully being one size fits all, but that concept is outdated in the 21st century much like Muslim and Hasidic clothing observances for women.