Fairies are Oh So… Neolithic July 17, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Prehistoric , trackback

In his early career as a fairyist, Beach gently kicked at the idea that fairies and vegetation were connected. All this modern nonsense about fairies in roses (‘she was small with pink taffeta wings and…’) was probably getting on his nerves. But he’d now like to apologise to folklorists, to historians, to fairy-believer and, should they exist, to the fairies themselves. Fairies are intrinsically connected with fertility and vegetation and only a dolt would ever have doubted it: note to self, do not, in future extrapolate on the basis of the weak brew that is nineteenth-century English fairylore. However, now this truth has been revealed to Beach a new thought has struck him: are fairies Neolithic or Paleolithic?

The Neolithic is the moment in history where hunter gatherers choose to settle down and grow things. There may have been some semi-agricultural efforts before, but the turnips and maize are only really whipped out when the first villages start forming lego-brick style. Fairies, it follows, are a creation of the Neolithic: they are the anxieties of folk sitting in the field at the end of day and waiting for the magic of growth, harvest, digestion, excretion and planting. OK, hunter gatherers, and particularly the all important gatherers, may have sometimes worried about berry or nut crops, but the very range of their food would mean less terrified focus on green shoots in fields. If there are no wild raspberries, then pick wild garlic… Elizabeth Barber’s very good Dancing Goddesses, connects dancing, fertility and fairies with the beginning of agriculture. Beach also find the idea of matching fairy societies under the hill intrinsically connected to a settled agricultural way of life: fairies like Neolithic people are tied to a portion of land.

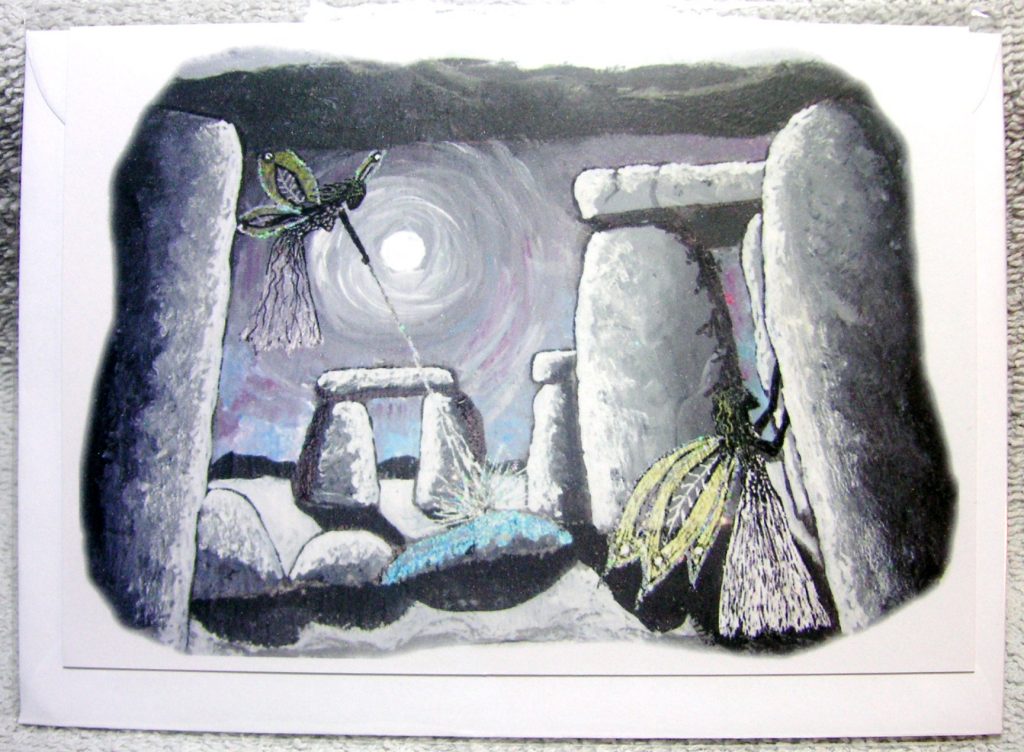

There were fairies, then, at Stonehenge. But what was there before? What do you find in the great hunter gatherer peoples of Euroasia and Africa? Presumably, the most important relationship was between the hunter and his prey. Out of the village animals are more frightening. Perhaps, then, the main supernatural entity was a shape-changing beast: which would make black dogs, bogeys, bogles, Hedley Kow and the like a descendant of the horror of the forests, c 40,000 BC. Beach is betting that there were witches, too. But then there are always witches… And there were ghosts, of course. Are there comparative studies of hunter-gatherer religions that can help? Most are so disappointing…

Does anyone want to make the case for Paleolithic fairies: drbeachcombing At yahoo DOT com Bring it on!

Leif writes, 31 Jul 2016, At least some hunter-gathering societies have fairy traditions. Two examples follow:

The legend of the fish women, from Wilson, Herbert Earl. The lore and the lure of the Yosemite. San Francisco, Calif., A. M. Robertson. 1922. p89

By the River She Made Baskets, from Goddard, Pliny Earle. Hupa texts. American Archaeology And Ethnology Vol. I No. 2. University Of California Publications. March, 1904.

These examples are respectively from the Miwok and Hupa native peoples of California. The California Indians were hunter-gatherers, and for the most part migratory. The fairies in these stories correspond closely to our naiads and nixies. They are in all clearly indigenous– in Goddard, elderly Hupa eyewitnesses recount the first contact with white men.

Whether western fairy traditions have paleolithic roots is, of course, a different question– and one not so easily answered. A century ago, folklorists applied the Aarne–Thompson classification system and the Finnish historic-geographical method in the romantic hope that folktales would give insight into national culture and beyond– perhaps even into the ‘wandering time’.

There are two kinds of fairies: the spirits of the household and farm, and the spirits of the wild– the lakes, rivers, forests, and mountains. One can make a good case that belief in household spirits arose in an agricultural era. But with the spirits of the wild, the case may not be so strong.

One wonders how fairies will fare when most people live in large cities. If fairy belief arises from man’s way of life, what new creatures will we encounter in the landscapes of the future?

Bruce T, 31 Jul 2016, on the shady line between agriculture and hunter gathering, ‘You may want to take a look at the works of the American ethnologist, John Swanton. Swanton’s primary work was the former tribes of the Southeast and secondarily with the the intensive, complex, fishing and gathering cultures of the Northwest Coast. The natives of the Southeast, while being primarily agricultural peoples at the time of contact, hadn’t been reliant on agriculture as the primary food source for the depth of time their relatives in Mesoamerica had, maize agriculture only became prominent in the region with the development of Eastern Flint Corn in roughly the 8th Cen. of the first millennium of the common era. It was shorter maturing variety, that spread rapidly throughout the eastern half of North America below roughly 45 degrees north. Even with the coming of maize and stratified societies, hunting and gathering remained a vitally important source of food until well after European contact. It was one the major reasons for conflict between Native Americans and early European settlers in North America as European land use was much different than that of the Natives. The Europeans didn’t respect the near empty buffer zones the Natives kept between one another as hunting areas, they would plop themselves down in the region, start farming, and either decimate or frighten off the large and medium sized game that was so vital as a foodstuff to the Native peoples. As both regions were in transitional states, settled, stratified chiefdom’s on the Northwest Coast to take advantage of the several massive salmon runs a season, and other marine resources, and the large maize/beans/ squash oriented chiefdom’s of the Midwest, Southeast, and Great Lakes that still relied heavily on hunting and gathering, the works of men like John Swanton and later Charles Hudson (no relation to me) on the folklore of the Southeast might shine a bit of a light on what was going on in Europe in it’s early swing from a hunter gatherer lifestyle to a sedentary agricultural one.’ And for fairies: ‘Now on to the the association of fairies with the earth. Psychotropic mushrooms and plants were likely well known in the Paleolithic. Rings of mushrooms are obviously called fairy circles for a reason. Places associated with fairies or supernatural beings may have been where these plants and fungi were found in abundance long before anyone took a digging stick to the ground to plant crops. The various kin groups of a hunting-gathering clan may have gathered at the areas when these items were in season for the shamans to do their thing and everyone to get lit while perhaps choosing a mate. The ground in the area where these various things grew in abundance may have come to have been seen a) as holy, and, b) as ours, with the things they saw in the altered states induced by these substances associated with that patch of earth. It may explain why some of the earliest layers of construction in the bank and circle type sites that we see as an early Neolithic phenomena in Western Europe are turning out to actually be from the late Mesolithic. In a way it’s saying, ‘This is where the magic happens.’’