Wolfe and the Seargent June 12, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

This little snippet comes from 1827 and Hone’s Table Book. It describes, of course, the death of that great British hero, James Wolfe, just outside Quebec, in 1759, one of the most famous moments of the march of Empire. But it adds a detail that most Wolfe’s biographers have ignored…

It is related of this distinguished officer, that his death-wound was not received by the common chance of war. Wolfe perceived one of the sergeants of his regiment strike a man under arms, (an act against which he had given particular orders,) and knowing the man to be a good soldier reprehended the aggressor with much warmth, and threatened to reduce him to the ranks. This so far incensed the sergeant, that he deserted to the enemy, where he meditated the means of destroying the general. Being placed in the enemy’s left wing, which was directly opposed to the right of the British line, where Wolfe commanded in person, he aimed at his old commander with his rifle, and effected his deadly purpose (251).

The story sounds like it has crept, on all fours, from epic poetry and made its way into a Rule Britannia history text book. Is there any chance that this happened? Well, first, Wolfe had a reputation for hard military discipline: while not being a martinet. Second, the French army included a colonial militia in which there were doubtless English as well as French-speakers. So it is conceivable. (Wolfe had arrived in what is today Canada in early 1758 so the sergeant would have left the British army and moved to the colonials in a brief space of time).

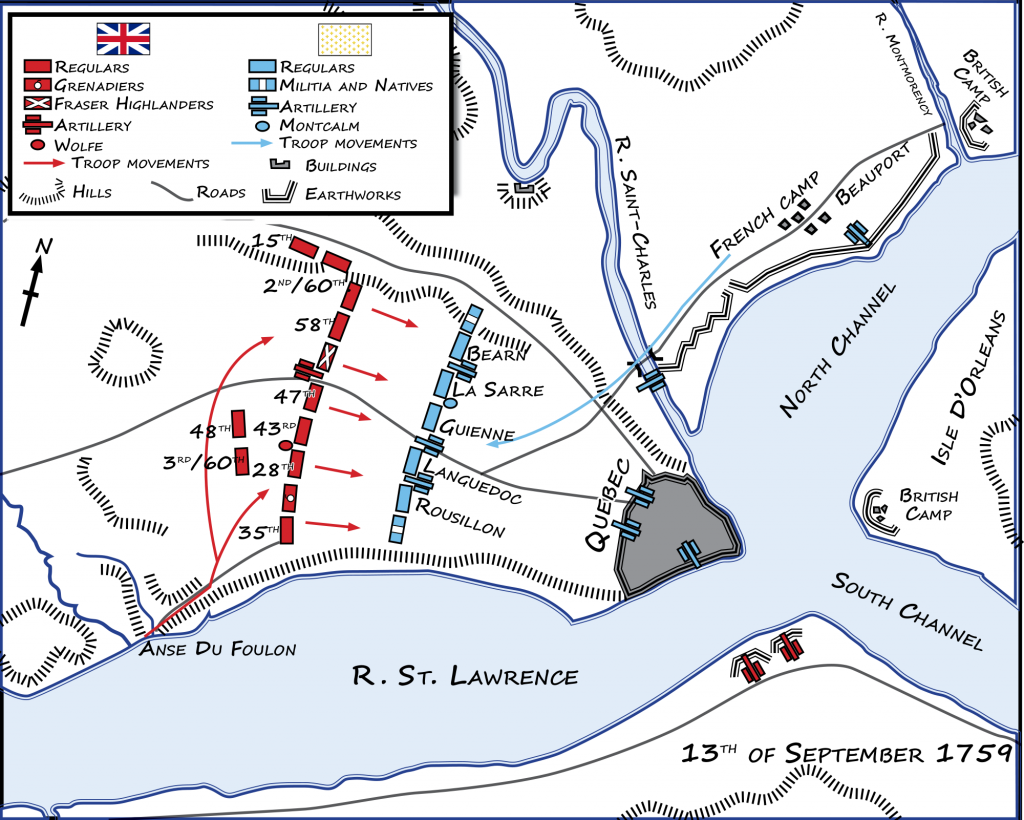

More problematic is the shooting. There were colonial sharpshooters that day, but apparently on the other side of the battlefield. Most normal troops using muskets would not have had the technology or the calm to aim so accurately at their enemy. Of course, it is just possible that ‘the sergeant’ shot in Wolfe’s general direction and thought he scored. Wolfe was shot three times that day: one bullet grazed his wrist earlier in the afternoon, then, at his death, one went into his stomach and one, the mortal shot, into his heart. The last two bullets were almost certainly shot by French ‘regulars’ rather than the colonials who held either flank: Wolfe was on a rise towards the centre of the fighting.

Other examples of invented adversaries: drebachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

Bruce T writes, 30 Jun 2016, ‘I wish there was a distance scale on that map. There was British General killed in the Revolution by a sniper who’s shot was paced off at 300 yards from high in a tree. (The name and battle escape at the moment, it’s been a long day.) As it’s still a part of American military lore, you’re probably looking at the maximum range of the long-barreled Pennsylvania rifle in the hands of sharp eyed sniper shooting from some type of rest. Speaking as someone who has spent his life around and shooting firearms, a 300 yard kill shot with rudimentary sights is amazing in and of itself. The Pennsylvania rifle would cost a man nearly three years of wages in that era. They were handmade and generally fitted to the man they were made for. The colonial militia on the British would have had units of sharpshooters with them, the French side not so much, a few picked up in trade or captured in war carried by loyal French frontiersmen their Native allies, but nothing along the numbers on the British side. Now let’s get to the nub, a British Sargent at that time went into battle armed with a spontoon, mostly to keep his own men from breaking and running when firing and taking fire in ranks tens of yards apart. You have to shoot a rifle regularly to be a good shot. Our Sargent was used to firing a musket when he was in the ranks, but that is a glorified shotgun at best, accurate out to about 50 yards. Now add the value of a Pennsylvania rifle. Who would loan one to Sargent who had never handled such a weapon? If he doesn’t load it properly that rifled barrel can explode. My money is on either a Native sharpshooter or French trapper, well concealed and shooting from a rest with the remote possibility of the Sargent whispering in his ear, “That’s him, the guy in the big hat on the bay horse.” [Then a few minutes later] I was looking at the French lines with a cooler brain a few minutes back. If Wolfe was killed by a rifleman, my guess is the shot came from the militia and Native ranks to the southeast, closest to Wolfe. They would have been taking potshots at him all day and had the weapon to do the do the job.