Lee’s Luck May 11, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

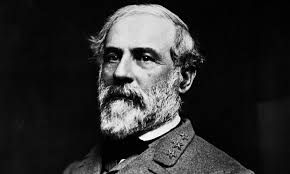

Robert E. Lee led the army of North Virginia, the central institution of the Confederacy, for just under three years (1862-1865). In that time he was able to rely on the most important military resource of all: not acumen, not courage, not atom bombs but sheer dumb luck. In Lee’s case the luck was deserved: there is no questioning his pep and daring. But there are still striking occasions when his army’s survival depended on Lee’s rolling three successive sixes. Two moments stick out and both involve last minute reinforcements arriving at just the right moment in just the right place. The first took place on the battle of Antietam (1862) when one of the Union’s less brilliant generals, Burnside, began to push the Confederate right. Lee was on the wrong side of the Potomac and a rout here would have been devastating: it might even have ended the war. The Confederates risked being pushed away from the crucial Boteler’s Ford: the only easy route back to Dixie. However, just as the right flank looked as if it would break A. P. Hill’s division arrived, at 3.30 pm, on the field from Harper’s Ferry, after an exhausting seventeen mile march. They were sent in by Lee and the Union’s momentum stalled and southern lines hardened again. There are many unanswered questions about that day and most of them are about choices made on the Union’s side: what if Burnside’s men had waded over Antietam Creek instead of using the bridge; what if McClellan had pursued Lee; and most importantly what if McClellan had employed all his troops? But on the Confederate side the only important question is what if Hill had arrived an hour later? An even more dramatic case of Lee’s reinforcement luck came at the Battle of the Wilderness in May of 1864. Here the Confederate right (commanded by the same A.P. Hill whose arrival at Antietam had been so important) fighting on Plank Road, simply routed under a devastating early morning Union attack on the sixth. Only Confederate artillery, personally commanded by Lee, stood between the Union and victory when, to Lee’s intense relief, his most trusted commander Longstreet arrived on the field and was able to smash, with his Texans, into the pursuing Federals. The Union soldiers, who believed that they had been chasing a broken army, suddenly found themselves facing some of the most battle effective soldiers in American history. Luck always had its price though and later that same day Longstreet would be shot in the throat (in a friendly fire incident) and Lee would lose his ‘war horse’ at a time when he had desperate need of good subordinates.

Other examples of last minute reinforcements changing a battle: the Prussians at Waterloo… Others? Drbeachcombing At yahoo DOT com

20 May 2016, Stephen D, an old friend of the blog: Not sure arrival of Prussians at Waterloo really counts, since Wellington’s dispositions had always been made on the assumption that they would, eventually, arrive.Would suggest instead, Marengo, 14 June 1800: Napoleon while facing the Austrians mistakenly sent considerable forces away on both flanks, was taken by surprise when Austrians attacked and was driven back, rescued about 5.30 by Desaix from the north who had heard the sound of cannon and marched towards it. Desaix is said to have told Napoleon “This battle is completely lost, but there is still time to win another”. He died leading the successful counterattack. Had he survived, Napoleon might never have forgiven him; as it was, he altered the account of the battle to make it appear all had gone according to plan. Also Kasserine, February 1943: American II Corps commanded, in the loosest sense of the word, by General Lloyd Fredendall who strives with Mark Clark for bad pre-eminence in contemporary American military history; strung out in southern Tunisia in positions incapable of supporting each other, and trained for attacking the by-definition-weaker enemy but not for defence; attacked by surprisingly unweaker Rommel, driven back fifty miles in considerable disorder, rescued by British infantry and artillery moved urgently south by probably underrated General Anderson. Unclear at the time whether blame should fall on Fredendall or Allied Supreme Commander in Tunisia, General Eisenhower: latter eventually sacrificed former, if promotion and recall to USA to command Second Army counts as sacrifice.

Bruce T writes in: It may be better rephrased as Lincoln’s Bad Luck. The South simply had better officers. It’s no little matter that the command of either the Union or Confederate Army was Lee’s to have until his home state of Virginia seceded and Lee followed. He was the best military mind in the country when the war was breaking out. Two, he’d served with most of his officer corps in Mexico a decade and a half before. Lee was simply getting the old gang back together. Lee’s army fought in territory he and his men had been familiar with all of their lives. At Antietam, McClellan was already operating in hostile territory. Maryland, heavily pro-Confederate was only being kept in the Union by force of arms. Lee was still in “Dixie” in Maryland. McClellan would, by crossing the Potomac into Virginia to pursue Lee, in Sun Tzu’s words, been fighting the enemy on “death ground”. Not only would he have had to faced Lee’s army determined to fight it out to the end, his men would have been open targets for every male within 15 or 20 miles old enough fire a gun rushing to the fight. His supply lines, strung out on unfamiliar roads, would have likely been shredded by irregulars. His men not knowing the minor fords at the heads of pools on the Potomac, would have been unable to make a quick, orderly retreat, if needed. McClellan was a very prudent man, a bit too prudent for Lincoln, which got McClellan the boot. Why Burnside insisted on fighting over the old stone bridge is apparent if you’ve been there. The creek is shallow, but the banks are steep. Union soldiers advancing across the creek would have been ripped apart by the Confederates shooting down on them in volleys at point blank range. It would have been a slaughter. On the Wilderness, I agree with you on Lee being lucky. His army was so depleted by the Wilderness Campaign, and the Union’s armament industry cranking at full capacity along with constant supplies of fresh draftees, it’s always surprised me Lee’s army didn’t fall apart then due to the sheer grind. If you’re ever in the D.C. area, rent a car and drive out to Antietam. It’s one of the few Civil War battlefields where the surrounding territory is much as it was in 1862. Plus, Harpers Ferry is just down the road. It’s a nice day trip.