Silly Crests May 7, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackback

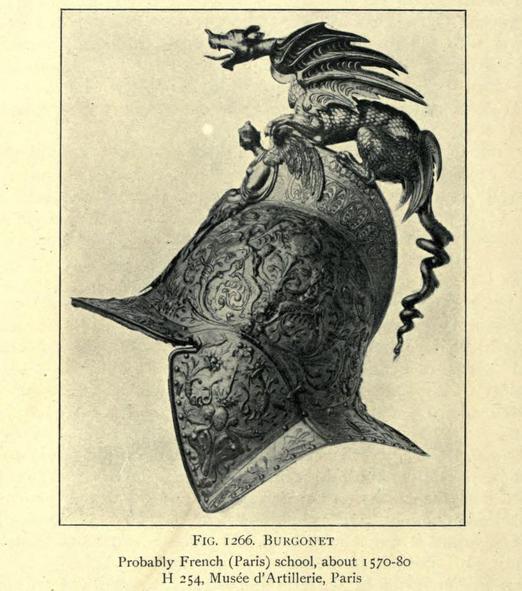

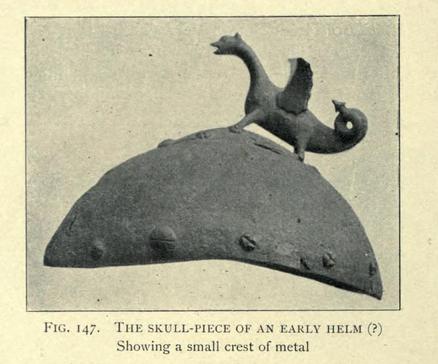

Beach has recently been looking lovingly through the various volumes of medieval armour and arms, particularly those of Guy Francis Laking (all online and all free if you have time and inclination). Particularly fascinating is the high silliness of the crests that were put on the top of the helmets. Above is perhaps the only truly convincing crest that Beach has yet come across: a dragon and a pretty frightening one. However, the others are often shockingly bad and shockingly strange. In defence of our medieval ancestors it is important to note that crests were not always used in battle: though might they actually have protected the wearer because it would be so difficult to resist hitting them off, instead of slashing at the wearer. Often they were worn in funeral processions and many of these survive in English churches where armour was left on tombs. Anyway here are some of the very best…

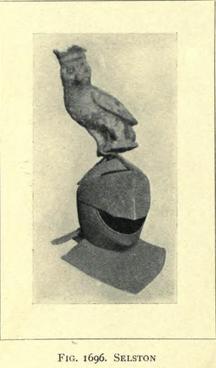

Wobbly owl.

A dollar-store bull.

A chicken: ‘And suddenly a hundred bowmen turned and ran because a man with a chicken on his head was walking towards them…’

A donkey!?!

Oversized griffin.

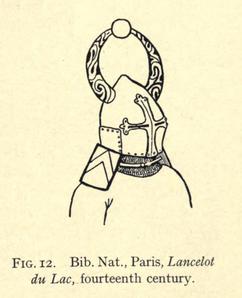

Not strictly a crest, more a wannabe Viking

More of the same

And here’s one that is genuinely interesting. A cute dragon. If this is eleventh century (??) then it is one of our earliest visual representations of a dragon from western Europe. Remember the Orkney dragon?

Other bizarre crests: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

7 May 2016: Bruce T. ‘Interesting that they seem to disappear with the advent of handheld firearms. Can’t have a peasant with a matchlock blowing the head off of Lord Throckmorton because his lordship was riding around in a funny hat. The British army’s insistence on marching around the countryside in formation wearing redcoats and tall hats was no minor factor in losing the American colonies. They made easy targets for country boys hiding in the woods with rifles. The British officer class’ habit of wearing plumed hats on the battlefield made them especially prime targets. Shoot the officers, fire a few volleys to inflict casualties in the ranks, then run off to fight another day. Ironically the Vietnamese used a similar model 200 years later on the Americans. In certain situations saluting an officer at forward base could get you busted in rank. Occasionally soldiers would do it purposely to officers who were getting too many men killed to send a little message while out on patrol. If the officer didn’t wise up, he might have an accident or worse.’

30 May 2016: Karl writes, ‘A few weeks ago I read one of your articles on medieval European helmet crests. It reminded me that some Japanese helmets had outrageous crests as well. Below is a photo from the Jidai Matsuri festival in Kyoto on 22 October last year. It shows someone dressed in the role of Takigawa Kazumasu, a supporter of Oda Nobunaga in the 16th century. I’ve seen other examples of elaborate Japanese helmets, but I had this picture available and thought you might be interested’ .

30 May 2016: If you think the European helmet crests are silly, what might you think of Japanese samurai helmets? The more eccentric were known as “strange helmets” or kawari kabuto. Masks and artificial facial hair were also sometimes part of the package.