Transvestite Vicar Ghost in Interwar England May 4, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback

This story haunted Beach more than any other he has covered in the last couple of weeks. There are several Beachcombian themes that come together and then rip a man’s life apart: ghosts, English deference (and its disappearance), the eccentricities of those in religious office, and the loneliness of each and everyone of us in our extraordinary compulsions. First, it might be worth noting that there were many nightwalkers in Victorian and Edwardian England who were often mistaken for ghosts. Some were men or women who used the night to walk naked through familiar countryside, and a rarer category were men who used the hours of night to dress in their wife’s clothing. Now enter from right stage Alfred Harold Read (AHR).

The sensational revelation of the strange conduct of a well-known Somerset Congregational minister in masquerading as a woman was made at Curry Rivel, a large village about eleven miles from Taunton. The minister concerned Rev. Alfred Harold Read, who has been at Curry Rivel since 1923, prior to which he was at St. Ives is an elderly man with a good record of service in the Congregational ministry. At Curry Rivel he lived with his wife in the new manse attached to the chapel, towards the building of which he had helped to raise the necessary funds. His wife has recently been away for a few weeks, but has now returned home [love this]. For two or three years there have been stories told in the neighbourhood of the appearance at night, and in startling circumstances to some people, of a tall, strange woman, but it has not been suggested that she accosted or molested anyone. Timid folk and children talked of ‘her’ as a ghost.

And now the turning gyre starts to fail. Given the vicar’s reckless behaviour, is it possible that he wanted to get caught?

It was nearly eleven o’clock night on a lonely road near the village that Mr. Read was challenged and made to declare himself. Earlier in the day he had been recognized when out walking in female attire, by Mr E. C. Pitman, the local postman. The postman’s story quickly got around the village and was regarded by many as almost incredible. It was dramatically confirmed late in the evening, when Frank Chorley, visitor to the Kings-William Inn. informed the landlord, Mr. William Weaver, and others present that he had just seen the strange ‘lady’ on the Burton-road. Leaving the house after ten Mr. eWaver [sic] and Mr. Chorley cycled out in search of the masquerader. They came upon ‘her’ near Stoney-lane, where Mr. Weaver made a grab at the person, catching hold by the wrists to prevent escape while Mr. Chorley shone his bicycle lamp into her face. Mr. Weaver, in describing the scene in an interview, says he did not then know Mr. Read the masquerader, but Mr. Woodrow, a leading member of Curry Rivel Congregational Chapel, who had followed, came up and immediately identified him.

Awkward! Beach wonders if in 1890 this would not have been the end of it. The parson or the squire could get away with this kind of stuff. By 1927, the Somme, Woolworths and the railways had put an end to that. Sometimes perhaps it is worth remembering that the goalposts had been shifted and that some of the players had not yet informed.

The woman’s clothes he was wearing consisted, of a tightfitting black hat and veil, dress worn beneath a red mackintosh, white stocking and black patent shoes with high heels.

This is lovingly repeated in report after report. Beach, without mentioning the word ‘man’ or ‘transvestism’, has discussed the get up with the four Beachcombing women (or at least the three sentient ones) and all agree that the combination is in poor taste. We now have an almost unbearably painful scene. AHR goes home and then ‘bumps into’ Weaver the day after on the way to the post office. Oh England!

‘The next morning’ states Mr. Weaver, ‘when going to the Post Office I met Mr. Read, who told me he did not think he had done any harm in masquerading as a woman. No one, not even his wife, he remarked, knew anything about it. He had heard that many girls and young women got into trouble or got molested, and he had posed as a lady to see if that were true.’

At first, according to some reports, AHR claimed that he was doing it to get material for a novel. In any case, whatever you think of the human tragedy unfolding you have to admire AHR’s sheer bloody cojones in what follows. Beach certainly would not have had a tenth of the courage of this man, who was fighting for his reputation and his life in an unforgiving interwar English village.

The discovery of his identity as the masquerader was promptly followed by Mr. Read issuing by handbill an invitation to the public to attend meetings at Drayton and Curry Rivel to hear his explanation. The handbill was headed, ‘Talks by the Masquerader,’ and invited attendance at separate meetings for men and women, to which boys and girls under 16 would not be admitted.

Beach can’t help noting here that presumably these boys and girls had sometimes passed ‘the tall woman’ on the road at night. In any case, only one of the meetings took place.

The Drayton meetings were held as advertised in the village hall, but those arranged for the subsequent evening, to take place in Curry Rivel Chapel, were, cancelled. Mr. Read had himself Communicated with the Somerset Congregational Union authorities, and suggested an inquiry into his action, if deemed advisable. A Taunton member of the County Union Committee, before whom the matter has come, stated on Saturday that the Curry Rivel meetings would not have been held in the chapel in any case.

What went wrong at Drayton? AHR seems to have been barracked by his erstwhile congregation, while offering a simply incredible explanation. At least he didn’t mention the novel: Dog Collar Days, High Heel Nights?

As it transpired Mr. Read was found too unwell, after his Drayton meetings, to proceed any further with meetings or services, and he has been ordered complete rest by his doctor. He was therefore unable to take part in the harvest festival services at the Curry Rivel Chapel yesterday. His place was taken by former minister, the Rev. H. Kirkpatrick, of Shaftesbury. At his Drayton meetings, where the same resentment was shown in the form of interruptions and comments, Mr. Read stated that he had become depressed at the apparent degeneration of modern morals and manners, and he resolved, without consulting anyone, to make a personal investigation, in the guise of woman, in his own locality, also at seaside towns and elsewhere.

Here are Read’s own words. In other reports we learn that he refused to talk to the press and just gave them a transcript of what he had been said. One interesting argument missed out here, but present in some other reports is that sometimes the police dressed up as women (really?) when they wanted to catch a miscreant. Read doubtless lovingly crafted the words, but nothing was going to get him out of this particularly hole, with its jagged glass walls.

‘It was my intention,’ he said, ‘to discover what was the attitude of the ordinary man to the ordinary woman going alone on country roads rather late at right [sic, night], making no advances — a woman who became absolutely silent when any sort advance or familiarity was made to her by a man. To my surprise and intense satisfaction, though I walked on many miles on various occasion, there was not one who became at all troublesome to me. Some will say it was because I was no engaging female. My only reply to that is that not a few opportunities would have opened out if I had given any sign. After having proved again and again all the local districts, as far as I could that men are far more chivalrous to women than I had imagined, I resolved to confirm and establish my convictions by visiting other populous areas. My experience was just the same, with one exception, at a place some distance away, where I sat on the sea front and suddenly felt a man leering at me. It was a terrible feeling, and I quickly moved away. Men, I raise my hat to you,’ declared Mr. Read, ‘I can truly say that you never had as high a place in my esteem as now. The lurid Press, that give so much space in their columns to sensation, are not fair to you. The heart of English manhood seems sound as ever. I have confirmed by these experiences your loyalty to the instinct of manhood, your genuine chivalry towards women and your high respect for those who are most inaptly described as the weaker sex. Now that this strange, and perhaps foolish jaunt of mine is over, I have apologized to everyone and I trust that they will all be ready to forgive me this spasm of folly’.

Of course, Read might have been sincere, these might have been words he whispered himself as he walked along and felt the silk on his legs, but they can only ever have been a very partial truth: he had done this for three years… Did his wife stay? Were his letters published in the local papers? Did he ever do anything foolish again? Was his grave tended? Drbeachcombing At yahoo DOT com Beach has come up short on all this.

Source: Anon, ‘A Minister’s Masquerade’, Western Morning News (19 Sep 1927), 4

Beach can’t resist including one of his favourite Spanish songs here Juana el loco, describing a man night-walking in stilettos at the end of Franco’s Spain, by the great Sabina.

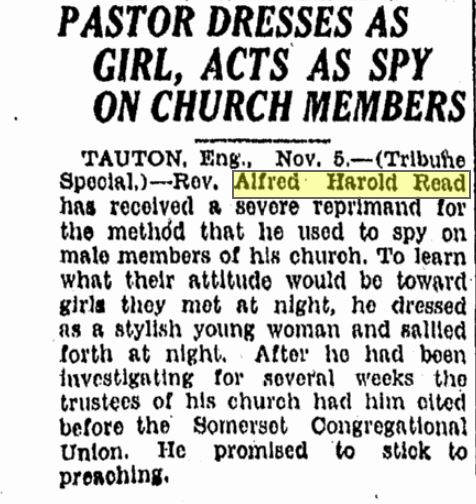

7 May 2016, Chris from Haunted Ohio Books with a fascinating piece: I’m attaching an article from the Tampa [FL] Tribune 6 November 1927: p. 31 about the reprimand given to the transvestite vicar. As late as 1933, a short account from 1927 was being used as a newspaper squib.

Last October I gave a paper called “The Woman in Black: Victorian Mourning Dress as Criminal Disguise” at a Costume Society of America symposium. [This is a professional association museum curators, costume historians and others interested in the history of dress.] One of my points was that many of the ghostly “women in black” who flitted around in the dark, kidnapped children, and terrorized neighborhoods were probably transvestite men. They are often described as being exceptionally tall and many newspaper accounts of the women in black panics suggest that the apparitions are men in women’s clothing. This was a criminal offense and men caught by the general public might be roughly handled.

An excerpt:

Cross-dressers were considered mentally aberrant and were sometimes sent to lunatic asylums. In 1848 Columbus, Ohio, was one of the first cities to pass anti cross-dressing laws; some 40 other cities soon followed their example, making it illegal to wear clothes contrary to one’s sex. Penalties became increasingly severe. In San Francisco, for example, Revised Orders 1863 said that cross-dressers would be guilty of a misdemeanor, and on conviction, would pay a fine not exceeding five hundred dollars. In 1866, the penalty increased to a $500 fine or six months in jail; in 1875, it went to a $1000 fine, six months in jail or both (General Orders 1875)

Of course none of these laws stopped men from dressing as women. Few were criminals trying to escape detection, but the act of wearing women’s clothes made them criminals. As Clare Sears writes in “Electric Brilliancy: Cross-Dressing Law and Freak Show Displays in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco,” public, but not private cross-dressing was against the law and, she notes, “As such, cross-dressing was marked as a deviant and secretive practice, rather than a public activity and identification.”

A widow’s garb was the perfect cover for a transvestite, who, given the usual domestic organization of a 19th-century working-class household, had little privacy or time for cross-dressing. It allowed them to walk abroad publicly, dressed as a woman; hiding in plain sight. The act of wearing widow’s weeds was, for transvestites, both a criminal act and the concealment of that criminal act.

In addition, mourning clothing was readily accessible. A man might borrow the weeds his wife had at home. Mourning goods could be purchased second-hand or through the mail. And security was guaranteed by the fact that few persons would have the courage or the impudence to walk up to a veiled widow in the dark and remove her veil. I found only a single case among hundreds of spectral Women in Black sightings, where a young Connecticut woman pulled the veil from the face of what turned out to be a well-known young man in widow’s weeds. His motive for doing so was elided by the newspaper.

I went on to describe social attitudes towards widows–there was a religious connotation to widows’ weeds, sanctifying the wearer and preserving them from casual molestation. The veil was psychologically impregnable, shielding the widow behind its social barrier.

If only the good Rev. had thought to dress as a widow, he might have escaped because few people would have dared lay hands on him. The black hat and veil worked, but the red mac was an unfortunate choice. In looking at other 19th and early 20th-century reports of transvestites arrested, I find that their clothing is often either badly coordinated as if they had snatched things at random from clotheslines or their wives’ wardrobes or exceptionally gaudy, showing a sad lack of dress sense, not unlike the Rev. Alfred’s (although I have to add that the white silk stockings with black patent shoes were actually correct female fashion for 1927.)

But my hat is off to the Rev. Alfred for his thrilling address about the Heart of English Manhood. For stirring qualities, it stands with the St Crispen’s Day speech.’

Thanks, Chris, this won’t be bettered!

12 Feb 2017, Chris from Haunted Ohio Books points out that the Somerset story has just appeared in Somerest Live: Beach knows that there is a 70% chance that this story is no longer on the internet, so, as there is some new information, he has also taken a scan of the article by Laura Linham for posterity. If Somerset Live is unlinked above then click on the image, please!

Invisible, 30 Mar 2017, with another cross dresser with a feeble excuse: read and weep and perhaps just laugh a little.