The Last African Slaves to Be Brought to America: Eyewitness Accounts April 21, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

The slave trade to America was banned in 1807, but slaves were still brought to America illegally in the decades that followed. The last known slave ship that brought slaves across the Atlantic was the Clotilde in 1859. What is extraordinary about the Clotilde’s journey is that the young slaves who were sold in Alabama, lived to become free citizens, once the Confederacy had been defeated, and uniquely were able, in the early twentieth century, to record their experiences of being enslaved, not as something passed down from a great grandfather, but as a painful and all too personal memory. It means that many of the events they went through can be described in the words of the slaves themselves.

Let’s, first, give the slave-trader’s perspective on this. The Clotilde was allegedly sent across the waves as a bet: could Southern élan get around Federal anti-slaving laws? (This at least is the ‘tradition’ recorded in the early twentieth century.) The vessel’s captain was one Captain Foster. Foster crossed to the territory of the Dahomey (modern Benin) and there bought slaves from the local monarch. He may have purchased close to 150 slaves, but after getting 116 into the hold of his ship he decided to fly because he thought that the Dahomey were preparing to attack him: he may have been right. Foster then sailed over to Alabama and disembarked, with great secrecy, burning the Clotilde as a precaution, before selling the slaves off. Many ended up on the Meaher plantation. The need for any secrecy ended with the beginning of the Civil War and the slaves were freed after that conflict and settled at Africa Town just outside Mobile (another post another day).

Now for the slaves’ perspective. All the quotations in what follows come from Clotilde slaves remembering their ordeal in the early twentieth century. The vast majority were Tarkars, an agriculturalist tribe in the West African interior, famous for their honesty and civility. One morning the Tarkars woke into a version of hell: their village had been attacked by a Dahomey raiding party. Interestingly, the raid was led by some of the most fearsome African troops of that or any century, the Dahomey Amazons (a previous subject of this blog). The Tarkars suffered one of two fates: they were killed and decapitated on the spot or they were (if they were young and looked valuable) hurried into the slavers’ column and marched towards the coast. One of the horrors of that journey, the slaves later remembered, was marching side by side with the decapitated heads of friends and relations carried on the spears of their captors.

The fates of the Tarkars are unknown: some presumably were sold to South America, some will have remained in Africa, but 116 slaves were bought by Foster and most of these were Tarkar. One was, instead, from the Dahomey tribe itself. There were also a handful from other tribes: allegedly because they had been visiting the Tarkars when the raid had taken place; perhaps they had mixed with the Tarkar on the journey to the coast or when afterwards they arrived? Foster, in any case, took his pick.

He looka , an’ looka, an’ looka. Then he point to one.

The slaves were brought down to the shore to be put on board the Clotilde and as they were being loaded onto the boat they were stripped naked by the Dahomey (an indignity so great that ninety year old men would complain about this seventy years later). Others were amazed because they had never seen the sea.

I hear the noise of the sea on shore, an’ I wanta see what maka dat noise, an’ how dat water worka – how it fell on shore an’ went back again.

Then they were taken onto a boat and pushed, all 116 into the hold, where they had not even space to sit up. They would lie numb for most of the transoceanic journey. They received little food and poor water.

‘Oh Loi! Oh Loi!… we so thirst! Dey gib us leetle beeta water twelve hours. Oh Loi! Oh Loi!’

After fourteen days they were brought up on deck to keep the blood going in their limbs. They were helped to walk around the decks.

We looka, an looka, an’ looka – nothin’ but sky and water. Whar we com’ from, we do not know – whar we go, we do not know.

Apparently no slaves’ life was lost on the crossing and after being hidden for a time on shore they were sold to new masters or parceled out among those who had sponsored the Clotilde’s journey. There is one almost unbearably sad incident after one group had been sold. As they were being marched through the Alabama countryside

[A] circus, moving from place to place, chanced to pass along the country road. To avoid danger or suspicion, the Africans were concealed behind the bushes with their backs to the passing show. As it passed, one of the elephants trumpeted; joy transformed the Tarkars, spread over their features, and ran through their limbs. To them the sound was as a cry from home, and as with one voice, gesticulating, tears streaming from their eyes, they shouted: ‘Ele, Ele! Argenacou, Argenacou!’ (‘Home, Home! Elephant, Elephant!’)

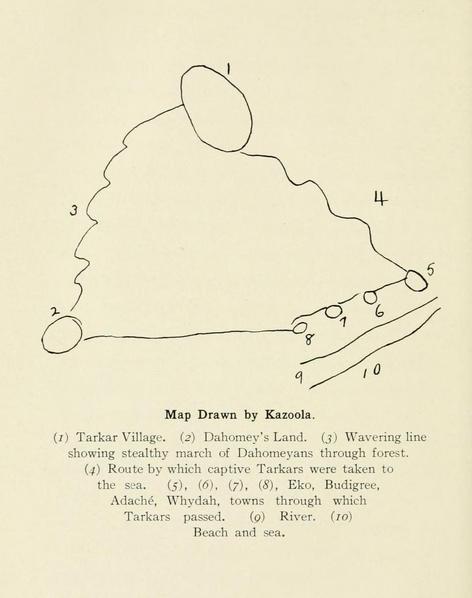

The map that heads this piece was drawn by one of these slaves Kazoola recalling the march from his village to the coast. It is a unique relic of the American slave trade.

Other first hand memories of men enslaved in Africa: drbeachcombing At yahoo DOT com

Sources: Zora Neale Hurston, ‘Cudjo’s Own Story of the Last African Slaver’, Journal of Negro History 12 (1923), 648-663; Emma Roche. Historic Sketches of the South (1914)