Huge Erratic Boulders: the Westmorland Thunderstones April 10, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackback

Thunderstones are a well known European and, indeed, international phenomenon, flint arrowheads or stone axes which were believed, by our early modern ancestors, to have descended from the sky in lightning storms. The typical praxis was that a sheep would be killed by a bolt of lightning and the family would discover, near the animal, a prehistoric weapon that was taken to be an instrument of the gods’ anger. However, Beach recently ran across a strange variation on the thunder stone that he has problems explaining. Jessica Lofthouse in one of her books about the traditions of northern England writes:

To reach Rosgill, I found paths about the river and woods, over high-flung pastures, some with thunderstones in them – huge, erratic boulders the superstitious Norse dwellers a thousand years ago thought to have been thrown about their fells by the angry arm of great Thor himself – and all with glorious western landscapes.

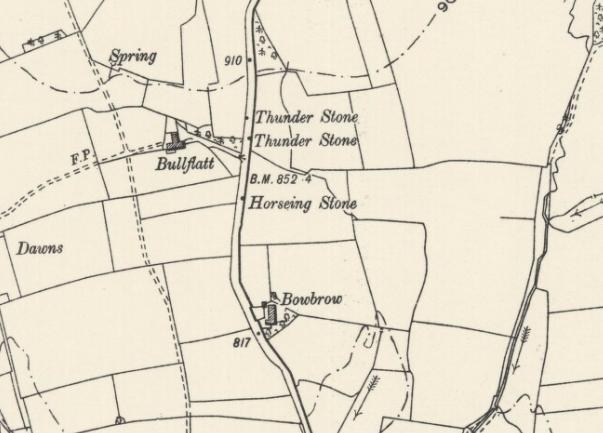

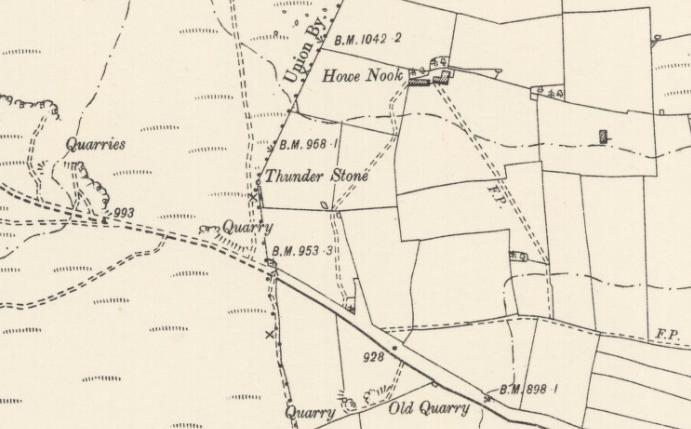

JL is absolutely right about ‘the huge, erratic boulders’. In parts of Westmorland, on the edge of the British Lakes, ‘thunderstone’ was the name given not to prehistoric weapons, but to massive rocks out on the moor. The image at the head of the post and the image immediately below come from Ordnance Survey Westmorland XXI.SE (1899): it would be an easy matter to gather ten to twenty from maps of Westmorland and there are sparse references to similar boulders in Cumbria. (Beach has been through Westmorland systematically, but not yet Cumbria.)

As to JL’s claim that thunderstones were the remnants of Thor’s arsenal this has a couple of points to recommend it. She is right that this is a part of the Britain where those Scandinavian psychos settled. It is also true that, in northern European mythology, great stones out in the landscape are frequently associated with giants’ throwing matches or duels across hilltops. It is not far from giant to Thor perhaps? The problem is the complete lack of evidence for this belief. Westmorlanders were not speaking routinely about Thor any time after the eleventh century. There is the suspicion that JL, as was her habit, made an intelligent guess here.

Can Thor’s thunderstones be paralleled elsewhere in northern Europe or Scandinavia or do we have to look for other explanation for these ‘huge, erratic boulders’. Perhaps a powerful regional experience with a meteorite? Drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

Note that Skeat’s Folklore article on thunderstones has no reference to these Westmorland curiosities.

Got a couple of pre answers here from twitterfeed: thanks to Grailseeker which contributed to the writing of this article.

30/4/2016 Norm wonders whether not a powerful local experience with meteorites. He goes on to write: No folk tales but we do have some giant glacial erratics around northern Ohio. Many are the size of dairy barns. The ice sheet came and went many times, many times in sheets a mile thick. They left a lot of stone and sand. I had an interesting sight in Guatemala once. I was traveling down the inter American highway when in a cow field there was what looked for all the world like our own glacial stone in the field. Not the case at all, they were bombs hurled from the subduction volcanoes some 30 miles away. Stones weighing in at 30 tons or better. Indeed, they came from the sky with thunder, I’m sure.

Alan writes in: On linguistic grounds, any association between the Westmoreland thunderstones and Norse beliefs is highly unlikely, for the following reason: the word “thunder” is Anglo-Saxon, not Norse; its introduction to the region therefore postdates any Norse superstitions or beliefs. If the name were Norse, it would probably be “thurstones” or something similar. The words “thunder” (Anglo-Saxon “Thunor”) and “Thor” are actually cognates, i.e. they are basically the same Germanic word (the North Germanic peoples dropped their “n” sounds at some point). In other words, it can be demonstrated that there is no unbroken tradition dating from Norse times, or dating from a time when a Norse-derived dialect was last spoken. This could be as late as the 20th century; Yorkshire dialect was spoken well into the 20th century, and most Scots words are of Norse origin, despite the Scottish emphasis on their Gaelic origins. Not for nothing is the northernmost part of Scotland called “Sutherland”. However, the conventional idea of thunderstones (as prehistoric hand-axes) probably inspired Thor’s hammer, Mjöllnir, as well as the axe carried by the Hittite “Weather God of Hatti”, although the concept may hark back to a common Indo-European heritage (interesting to note that lightning in Russian is “Molniya”, which is obviously related to Mjöllnir).

Bruce T writes: There are large erratic rocks like the “thunderstones” you’re speaking of across the entire Northern Hemisphere above roughly 42-45 degrees north, where the glaciers stopped at their peak in the last Ice Age. They were deposited as glacial moraine when the glaciers retreated. Even Central Park in NYC has several in it’s small confines. They’re as common as dirt throughout northern North America. No need to resort to meteorites to explain a simple geological process. Many of these erratics were treated as holy objects by Native Americans and the object of speculation of European settlers who saw them as proof that a race of giants had once inhabited the continent, not only being responsible for the the stones, but also the myriad of mounds Native Americans had erected across the eastern half of the continent. The European settlers at the time saw the Natives as a “degraded race”, incapable of erecting the mounds. They lumped the rocks and mounds together and attributed them at times to the giants of the Bible, Vikings, Romans, lost Hebrew tribes and other such silliness. There are mythos about the things wherever they’re common, much of it very similar to the thunderstone stories mentioned in your article.

Mike L sends in a link to a Wikipedia page with this information: Thurstaston Hill is the location of Thor’s Stone, a large sandstone outcrop and a place of romantic legend. In the 19th century it was supposed that early Viking settlers may have held religious ceremonies here. A visit to the site by members of the British Archaeological Association in 1888 heard an account by Rev. A. E. P. Gray, rector of Wallasey, that the ‘Thor Stone’ was also known in the locality as ‘Fair Maiden’s Hall’ and that children were “in the habit of coming once a year to dance around the stone”. This part of Wirral was certainly part of a Norse colony centred on Thingwall in the 10th and 11th centuries. However, geologists and historians now think that the rock is a natural formation similar to a tor, arising from periglacial weathering of the sandstone, which was later exploited by quarrymen in the 18th and 19th centuries.