Killer Cameras March 2, 2016

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackback

When many years ago Beach travelled in Sub-Saharan Africa he was warned by anxious parents, and relatives not to take photographs of the natives. They might believe that their soul had been taken. Where does this idea come from? And did anyone anywhere ever actually believe it? Well, a run through sources suggests that the idea spiked in the 1970s, and then deflated as it was found that non-western peoples were not particularly worried about the effect of kodak on their physical or mental health. Perhaps the belief had never been that strong, perhaps this technology had become unthreatening. Earlier in the twentieth century, in Frazer’s third edition of the Golden Bough there appeared the following ‘cut and paste’.

The Yaos, a tribe of British Central Africa in the same neighbourhood of Lake Nyassa, believe that every human being has a lisoka, a soul, shade, or spirit, which they appear to associate with the shadow or picture of the person. Some of them have been known to refuse to enter a room where pictures were hung on the walls, ‘because of the masoka, souls, in them.’ The camera was at first an object of dread to them, and when it was turned on a group of natives they scattered in all directions with shrieks of terror. They said that the European was about to take away their shadows and that they would die ; the transference of the shadow or portrait (for the Yao word for the two is the same, to wit chiwilili) to the photographic plate would involve the disease or death of the shadeless body. A Yao chief, after much difficulty, allowed himself to be photographed on condition that the picture should be shewn to none of his subjects, but sent out of the country as soon as possible. He feared lest some ill-wisher might use it to bewitch him. Some time afterwards he fell ill, and his attendants attributed the illness to some accident which had befallen the photographic plate in England. The Ngoni of the same region entertain a similar belief, and formerly exhibited a similar dread of sitting to a photographer, lest by so doing they should yield up their shades or spirits to him and they should die. When Joseph Thomson attempted to photograph some of the Wa-teita in eastern Africa, they imagined that he was a magician trying to obtain possession of their souls, and that if he got their likenesses they themselves would be entirely at his mercy When Dr. Catat and some companions were exploring the Bara country on the west coast of Madagascar, the people suddenly became hostile. The day before the travellers, not without difficulty, had photographed the royal family, and now found themselves accused of taking the souls of the natives for the purpose of selling them when they returned to France. Denial was vain ; in compliance with the custom of the country they were obliged to catch the souls, which were then put into a basket and ordered by Dr. Catat to return to their respective owners.

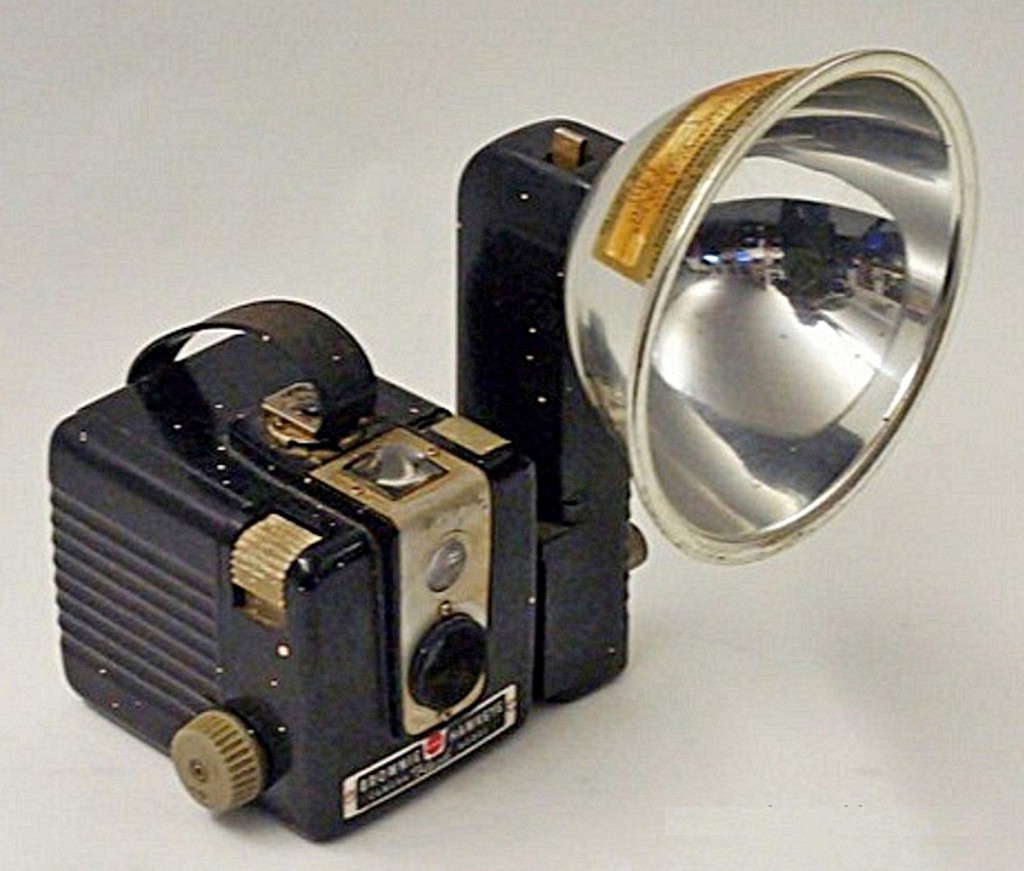

Most of Frazer’s references (and his discussion continues…) are early twentieth century. The reference to the Yao for example dates to 1902. Most of these stories after all depend on explorers having the technology AND on the ‘victims’ understanding what the photographic apparatus was actually for. So how far back into the nineteenth century can the idea be pushed. Well… Beach is quite proud of this early reference. This appeared in the Der Tel 19 Feb 1859. It relates to Syrian Lebanese.

The English, it is thought, take a daguerreotype of the students coming from Syria, and when they return, if they change their religion and go back to the religion of the country [Syrian Lebanese = Islam] the picture becomes black, upon which the English stab the picture, and the man whose likeness it is drops dead, wherever he may be, walking, standing or sitting.

Those fiendish Brits… A daguerreotype is of course an early photograph.

Can anyone go further back than 1859. drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

Note that for present purposes it doesn’t matter whether the Syrians really believed the dangers of the photograph: only that the idea circulated in the west.

25 Mar 2016: Chris S writes in ‘Still Life, an episode from the 1980’s reboot of The Twilight Zone. Apologies for it being on Dailymotion. Plot involves a camera with undeveloped film containing the souls of natives photographed back at the dawn of the 20th century.

25 Mar 2016: Bruce T writes We have similar tales in the States involving Native Americans in the mid-1800’s. As the Library of Congress is full of pictures of various tribal leaders dating from practically the introduction photography in North America, it strikes me as a load of manure. However, many Native groups to this day don’t allow their ritual and religious activities and/or sacred objects to be photographed or filmed. So there is a precedent of sorts. The interesting thing about Native Americans and photography to me is how fast they picked up on it as a way to make a dollar. When Sitting Bull was with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, he had people lining up to pay five dollars for a photo of him. Five dollars at that time was more than many people made in a week. It and his other earnings with Buffalo Bill allowed him to take care of his people. On the peak of the tale in the 70’s. This is about 10 years after the release of the Kodak Instamatic Camera. Thousands of American servicemen headed to Southeast Asia with the things.. As US Special Forces worked with the Hmong in Laos and the Montagnard in Vietnam, the rapidity of the development of the photo from one of those things might seem like magic. I know that the first time I had my picture taken by one in as a child in the mid ’60’s I was gobsmacked by the thing, and I was used to having my picture made on a near weekly basis. I can’t imagine what the impact would have been initially on swidden farmers in an upland jungle with access to a few types of metal tools?