The Churchill Coventry Myth September 7, 2015

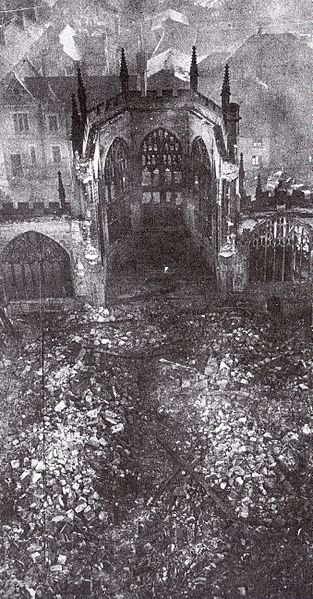

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackMoonlight Sonata was the German code name for the bombing raid on Coventry 14 Nov 1940, the first major German bombing raid on a British civilian target. Over five hundred German bombers shimmied over the city in thirteen waves. Most estimates put the number of deaths at just over five hundred hundred and the damage to the town was devastating: Coventry’s centre is entirely modern for the very simple reason that it had to be rebuilt from scratch. The memory of Coventry died hard. When British troops prepared to run onto Normandy beaches in June 1944 the loudspeakers on some ships instructed them to ‘Remember Coventry, Remember Dunkirk’, the great civilian and the great military disasters of the British war in the west. So much for the facts. Behind the disaster there is a longstanding conspiracy theory: namely that Churchill sacrificed Coventry to make sure that the Germans did not know that enigma had been broken. The conspiracy theory is expressed nicely in a novel by Robert Harris, Enigma (1995).

‘I think, it’s possible to know too much. When Coventry was bombed, remember? Our beloved Prime Minister discovered from Enigma what was going to happen about four hours in advance. Know what he did?’ Again Jericho shook his head. ‘Told his staff that London was about to be attacked and that they should go down to the shelters, but that the was going upstairs to watch. Then he went out on to the Air Ministry roof and spent an hour waiting in the freezing cold for a raid he knew was going to happen somewhere else. Doing his bit, d’ you see? To protect the Enigma secret.’ [365]

Beach has used the phrase ‘conspiracy theory’ above. Usually, ‘conspiracy theory’ has a negative ring to it. But in the midst of the Second World War when the UK was playing for the highest stakes and when its survival depended on carefully gathered intelligence… Well, is there actually something to this idea?

The allegation was, first made in The Ultra Secret, by F. W. Winterbotham. TUS was the book that broke the news of Britain’s decryption of Enigma to a rather surprised world in 1974: the UK and America had forgotten to mention after the war that they had tamed Enigma not least because a number of governments continued to use it. Winterbotham had a slightly melodramatic take on his personal experiences at Bletchley Park, but then who can blame him . The idea, then, became hard fact in Anthony Cave Brown’s A Bodyguard of Lies in 1975. From the very beginning there were voices lifted, however, against the claim. In 1976 N. E. Evans produced a very important article ‘Air intelligence and the Coventry Raid’, Journal of the Royal united Services Institute for Defence Studies 121, making the case against: Enigma decrypts showed that Moonlight Sonata was being planned, but not clearly what the target would be. Many other authoritative voices have since joined Evans including Martin Gilbert. In 1991 David Irving included the Churchill-Coventry story in Churchill’s War and supported the Coventry-sacrifice thesis. By 1995 Harris still felt able to use the story in his book and not suffer any particularly rabid criticisms: Harris knows his WW2 history.

The crucial episode, which certainly took place, was in a chauffeur-driven car, 14 Nov: could the passengers have imagined the arguments that forty or fifty seconds in that vehicle would lead to? Churchill was given a secret communiqué as he was being driven out to the country, at about 4.30 pm to spend a night away from the capital. After he had read the communiqué (and he alone read it) he ordered the car around claiming that London was going to be bombed and that he did not want to leave the capital in its moment of need. He then went up to the Air Ministry Roof, as Harris describes. Gilbert believes that Churchill returned because the instructions predicted an attack on London: Churchill did, rather melodramatically, walk around the Air Ministry Roof during bombing raids causing his staff grave concerns; Beach likes to think of it as Churchill’s childish, Boy’s Own side. Irving believes, instead, that Churchill had learnt that Coventry was being attacked and he went to the roof knowing that he would likely be safe. Whether or not British fighters could have done much to the waves of German bombers in the dark is a nice question: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com.

Beach would trust Gilbert’s judgment over Irving’s on this and on many other questions. But what he finds fascinating is the way that the myth has developed. Let’s pretend for a moment that we live in a world where Churchill made the dreadful decision to sacrifice Coventry. What is interesting is that most writers who have gone along with this have seen it as part of Churchill’s necessary strength. Churchill had, it would be argued, the iron courage to sacrifice an important part of a British city to keep the best kept secret of the war under wraps. If it had been applied to an ambivalent leader, a Mussolini, or a perfectly dreadful one, a Hitler or Stalin, the story would have been used to other ends, of course. Churchill’s enemies might not like it, but in British historical consciousness Winston still has a Teflon quality.