The Chester Cat Hoax of 1815 September 3, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackThis is a short story published some 90 years after the event it supposedly described: Chester is a city on the northern Welsh borders. This story is frequently retold in miscellany of the bizarre, local histories and Francis Wheen includes it in his marvelous The Chatto Book of Cats, 1993. There are three interesting points: the ‘amusing’ nature of the story itself (though pity the cats); the way the story changed in the telling; and the origins of the tale, which Beach can today reveal for the first time in two hundred years. The first account we’ve chosen comes from 1905.

To the Americans, who are at present visiting Chester, the old story of the extraordinary hoax is being retold. When Napoleon was about to be sent to St. Helena [1815], the town of Chester was flooded with handbills, setting forth that many families were to accompany the British regiment which was to watch over the emperor, and that as the island was overrun with rats, numerous cats would be required. Prices from ten shillings downwards were mentioned on the bills , in which prospective sellers were asked for cats, which prospective sellers were asked to leave at a certain address at a certain time. In response over 3,000 cats were brought to the address in bags, and so great was the crowd of people that panic ensued. Five hundred dead cats were taken from the River Dee, it is said, next morning, as the sequel to a cat hunt by the boys of the town. Seven, 28 Jul 1905, 6

Here is a slightly older version (1891) that cuts down to 75 years the period between the doing and the telling.

1815, when the vessel containing Napoleon was to sail for St. Helena, a waggish person in Chester, England, caused to be distributed in the town and surrounding country handbills stating that St. Helena was overrun by rats that without relief it would be impossible for the captive Emperor and his guards to live there. This being the case the Government had determined to send out a shipload of cats, the ship to sail from Chester. On a certain appointed day the King’s officer would be in the city and would pay 16s….for full grown toms, 10s. for female cats and 2s. 6d. for kittens old enough to feed themselves. The people in the surrounding country took the matter seriously, and on the day appointed thousands of cats were brought into Chester. The owners, finding they had been tricked, became angry, threw away their cats and started to sack the City Hall. The police were unable to deter them, and riot ensued, in which a number of the townspeople were injured by the infuriated country folk, who relished neither the jest nor the laughter at their expense. In the three weeks after the riot over 4,000 cats were killed in Chester and the vicinity. The jester was never discovered though a reward was offered for his detection and punishment. Whit, 11 Jul 1891, 6

The story is less dramatic but better told in 1840 in the Odd Fellow, 4 Jan, 3.

About the time of Buonaparte’s departure for St. Helena a respectably dressed man caused a number of handbills to be distributed through Chester, in which he informed the public that a great number of genteel families had embarked at Plymouth, and would certainly proceed with the British regiment appointed to accompany the ex-emperor to St. Helene; he added farther, that the island being dreadfully infested with rats, his Majesty’s ministers had determined that it should be forthwith efficiently cleared of those noxious animals. To facilitate this important purpose, he had been deputed to purchase many cats and thriving kittens as could possibly be procured for money in a short space of time; and, therefore, he publicly offered in his band-bills, 16s. for every athletic full grown tom-cat 11s. for every adult female puss, and 2s 6d. for every thriving vigorous kitten that could swill milk, pursue a ball of thread, or fasten its young fangs in a dying mouse. On the evening of the third day after this advertisement had been distributed the people of Chester were astonished with an irruption of a multitude of old women, boys, and girls in their streets, all of whom carried on their shoulders either a bag or a basket, which appeared to contain some restless animal. Every road, every lane was thronged with this comical procession; and the wondering spectators on the scene were involuntarily compelled to remember the old riddle about St, Ives: [St Ives poem quoted] Before night a congregation of 3000 cats was collected in Chester. The happy bearers of these sweet-voiced ones proceeded all (as directed by the advertisement) towards one street with their delectable burdens. Here they became closely wedged together. A vocal concert soon ensued. The women screamed; the cats squalled; the boys and girls shrieked treble, and the dogs of the street howled bass, so that it soon became difficult for the nicest ear to ascertain whether the canine, the feline, or the human tones were predominant. Some of the cat-bearing ladies, whose dispositions were not of the most placid nature, finding themselves annoyed by their neighbours, soon cast down their burdens, and began to box. A battle royal ensued. The cats sounded the war-whoop with might and main. Meanwhile the boys of the town, who seemed mightily to relish the sport, were actively employed in opening the mouths of the deserted socks, and liberating the cats from their forlorn-situation. The enraged animal bounded immediately on the shoulders and heads of the combatants, and ran spitting, and squawling and clawing along the undulating sea of skulls towards the walls of the houses of the good people of Chester. The cats rushing with the rapidity of lightning up the pillars and then across the balustrades and galleries, for which the town is so famed, leaped slap-dash through the open windows into the apartments. Now were heard the crashes of broken china; then the howling of affrighted dogs the cries of distressed damsels; and the groans of well-fed citizens. All Chester was soon in arms, and dire were the deeds of vengeance on the feline race. Next morning, above five hundred dead bodies were seen floating on the Dee where they had been ignominiously thrown by the two-legged victors. The rest of the invading hosts having evacuated the town, dispersed in the utmost confusion to their respective homes.

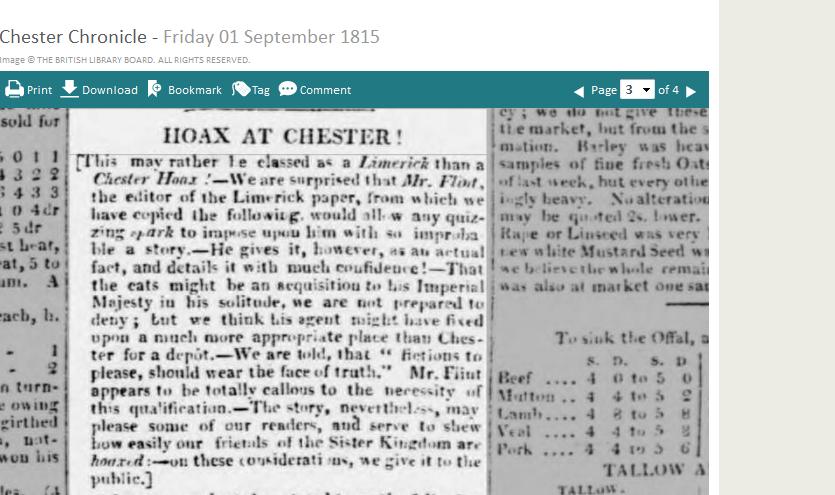

But can we trace a report back to zero year, 1815? Luckily yes. At some point in late August a Limerick paper included a more extensive version of the Odd Fellow account above: the Odd Fellow editor improved by cutting. This story then spread through the British papers, where it surfaced on several occasions: e.g. Cornwall in late September. Only in Chester was a slightly different article written. Before quoting the Limerick piece the Chester editor put in this note. Chester Chronicle 1 Sept, 1815, 3:

This may be rather classed as a Limerick than a Chester hoax: We are surprised that Mr. Flint, the editor of the Limerick paper, from which we have copied the following would allow any quizzing spark to impose upon him with so improbable a story. He gives it, however, as an actual fact, and details it with much confidence. That the cats might be an acquisition for his Imperial Majesty in his solitude, we are not prepared to deny; but we think his agent might have fixed upon a much more appropriate place than Chester for a depot. We are told, that ‘fictions to please, should wear the face of truth.’ Mr. Flint appears to be totally callous to the necessity of this qualification. The story, nevertheless may please some our readers, and serve to shew how easily our friends in the Sister Kingdom are hoaxed: on these considerations we give it to the public.

It is a beautiful example of how a fake story can take root. In 1815 the Chester paper was amused and outraged. By 1905 American visitors to the city were solemnly told the story as a fact. Modern accounts of Cheshire history do likewise. Other information on the Cheshire cats: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com