Roman Gutter Burials and a Non-Existent Line of Pliny May 17, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Medieval , trackbackIn Roman times dead babies and fetuses were not cremated as adults: references in Pliny and in Juvenal confirm this, as do archaeological findings. However, a fifth/sixth century Christian writers named Fulgentius (possibly a North African) has been read to mean that these not fully human humans were buried in suggrundaria:

Priori tempore suggrundaria antiqui dicebant sepulchra infantium qui necdum quadraginta dies implessent, quia nec busta dici poterant, quia ossa quae conburerentur non erant, nec tanta inmanitas cadaueris quae locum tumisceret; unde et Rutilius Geminus in Astianactis tragoedia ait: ‘Melius suggrundarium miser quereris quam sepulchrum’.

In olden times, the ancients called the places of burial of infants who had not yet reached 40 days suggrundaria because they could not be called graves as there were no bones there to be cremated, nor was the size of the corpse so great that it took up much space. From which Rutilius Geminus in Astyanax [a missing tragedy] said: ‘You would do better to miserably search for the burial place of an infant (suggrundarium) than for a grave.’

Unfortunately we do not know how old this custom was and how good Fulgentius’ evidence was for it: had he heard of this in his own lifetime or was he talking about a truly ancient custom of which no trace remained, other than an obscure literary reference? There is a chance that he was guessing: though 40 days sounds promising. The word appears in his Expositio sermonum antiquorum, a description of ancient and therefore obscure words.

The Romans generally liked to keep the dead away from their residential areas, banishing corpses outside the city walls. But perhaps in the case of miscarried children or very young babies exceptions were made: it depends how we interpret suggrundarium, and some other ancient authors including Statius. This word is almost certainly from Sub-grundarium, meaning ‘underneath the eaves’. There are two ways to read this. Was a suggrundarium literally a space beneath the eaves of a house: or was it, as Lewis and Short put it, ‘a niche in a wall covered by a projecting roof or eaves’. In the second case the niche in question could conceivably have been, say, in a cemetery.

The word suggrundarium is difficult to deal with because it only appears once in the corpus of ancient Latin: in Fulgentius, though he, in turn, had found it at least once, in the now lost play by a now forgotten playwright (date unknown). However, some confusion over Fulgentius’ words has led to an almighty mare’s nest, lined with feathers from the classics. Dorothy Watts writes in her very worthwhile Christians and Pagans in Roman Britain:

[T]he deposition of the bodies of very young children within the city bounds seems to have been the norm [in the Roman world]. Both Juvenal (Saturae 15.139) and Pliny (Naturalis historia 7.16.71) refer to the practice, the latter stating specifically that it was not customary to accord the cremation rite to infants who died before teething (that is 6 months old).

As a matter of fact Juvenal and Pliny do not state that very young children were buried within the city bounds, let alone that it was the norm, at least not in the passages referenced. They do state that it was normal not to cremate these very young children but to bury them. Juvenal has the tragic line: uel terra clauditur infans et minor igne rogi (or when the earth closes over a babe too young for a pyre). Pliny writes: hominem priusquam genito dente cremari mos gentium non est ‘It is not the custom in any country to cremate the dead body of any infant before his teeth come out’. This is quibbling, but DW’s next passage has a far more serious inaccuracy.

[Pliny] adds that it was the custom to bury these infants under the eaves of buildings (in subgrundariis). Some four centuries later, Fulgentius (Sermones antique 7), while interpreting subgrundaria, says that those who were buried thus were less than 40 days old.

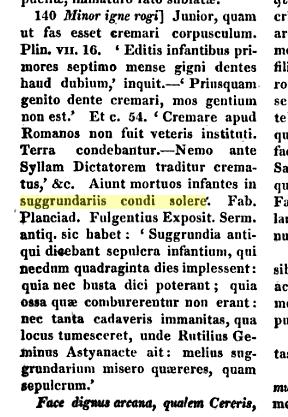

The strange inaccuracy here is that Pliny writes nothing about subgrundariis, at least in the editions available to this blogger. DW does not give a reference in the Natural History but includes in her note after the word ‘subgrundariis’ the relevant sentence: ‘Aiunt mortuos infantes in subgrundariis condi solere’ (They say that dead children were placed under the eaves: my translation). Beach’s guess is that DW did not put the reference because she could not find it, but had read it unreferenced elsewhere. Certainly, Beach has not been able to find it in Pliny: if you know better drbeachcombing at yahoo DOT com. In fact, this sentence seems to originate in an early nineteenth-century commentary on Juvenal: D. Junii Juvenalis Opera omnia, II, 744 (1810). The sentence is that of the editor, in other words it is nineteenth-century Latin, and appears immediately after a couple of quotations of Pliny. A screen capture follows.

Beach should say immediately that Dorothy Watts is far above him on the scholarly mountain of excellence, Beach is still on the scree slopes, and his many screw-ups in academic publications over the years make this look as inoffensive as a spot of milk on a baby’s cheek. However, it is instructive to see what a beautiful hall of mirrors has been founded on this misunderstanding. The first reference after 1810 seems to be in the Archaeological Journal from 1849 (‘Memoir on Roman Remains at Ickleford and Chesterton’, p. 21) when this Latin sentence is quoted as being in the Natural History VII, 54, which is right in as much as the chapter in question is on burial and cremation, but the quoted lines are simply not there! Beach’s guess is that the spot of ink after ‘solere’, visible on the screen capture, was interpreted as a speech mark. In 1858 in the Transactions of the Essex Archaeological Society (‘Remarks on Roman Sepulture’, 92) the words are quoted and assigned to Fabyan (see the screen capture above to see where this mistake comes from, Fabyan is actually Fabius Plancides Fulgentius). In 1936 they appeared again, as part of Pliny NH VII, 54 in the Natural History in the Report of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries (138). DW very possibly took her reference from one of these or another later work and, again, did not put the chapter and book because she was unable to substantiate it.

Beach has wasted a couple of hours on this question this morning because there was a genealogy of capable historians/archaeologists who made the same or related mistakes. They did so either because they misread (albeit in different ways) the passage in the 1810 paragraph from the note on Juvenal, or because they borrowed from each other (which is fine) without checking (which is dangerous). Does it matter? Well, it does because this mare’s nest has had several eggs laid in it. As we saw in a previous post it is now well-established in Anglo-Saxon archaeology that fetuses and children were buried close to church buildings in medieval times. Papers on this question have repeated that this was also a Roman custom, with the implication that this may have been borrowed from ancient times. Take the excellent work of Elizabeth Craig-Atkins on this question citing DW: ‘Eavesdropping on short lives’.

In her review of funerary practices afforded to infants in Romano-British Christian contexts, Dorothy Watts (1989, 372) cites several sources that suggest infants’ burials were made in the eaves (in subgrundariis). Roman polymath Pliny‘s Naturalis Historia, published around AD 77-79, specifically notes the exclusion of infants who died before teething from the cremation rite, and their burial under the eaves. Fulgentius, a fifth-century Carthaginian bishop, develops on this some 400 years later with the suggestion that infants who had not lived forty days would receive this form of burial (Watts 1989, 372). As with the undated folk myth highlighted above, the practice described here links the burials of the very young with the eaves of buildings, but implies that chronological age or rites of passage, such as teething, might have defined the age groups to which it was afforded.

This is a summary of DW’s work and any Anglo-Saxon archaeologist will have assumed, understandably, on the basis of Watts, that a passage with the phrase ‘in subgrundariis’ appeared in Pliny and that the custom it substantiates is confirmed at the end of antiquity by Fulgentius. In fact, there is no reference in Pliny and Fulgentius is very likely speculating about the meaning of an obscure Roman word, with who knows what success. The etymology of suggrundarium as sub grundaro (under the eaves) is a good one: but there is no proof that the word was understood at a later date as ‘under the eaves’ (as opposed to, say, to return to Lewis and Short, ‘a niche in a wall covered by a projecting roof or eaves’). The only way to establish a Roman custom glimpsed in Fulgentius as ‘under the eaves’ would be to do so archaeologically.

18 May 2015: Giorgio di Francesco comments this paragraph,

<(…) it depends how we interpret suggrundarium, and some other ancient authors including Statius. This word is almost certainly from Sub-grundarium, meaning ‘underneath the eaves’. There are two ways to read this. Was a suggrundarium literally a space beneath the eaves of a house: or was it, as Lewis and Short put it, ‘a niche in a wall covered by a projecting roof or eaves’. In the second case the niche in question could conceivably have been, say, in a cemetery>>.

The latin word is “subgrundarium” (“suggrundarium” is a late evolution of the term). Originally, it’s an adjective from the word “grunda” (that means “eaves”). When it becomes a substantive, “subgrundarium” implies “spatium”: so “(spatium) subgrundarium” means “the covered space existing between the end of the outest tile and the wall”.

Roman roofs were not very projecting and they were not like chinese roofs that you show in the picture, nor like modern roofs of northern Italy. When Romans wanted to make a projection, they built a porch…but the porch is not a “(spatium) subgrundarium”.

This is an intact roman roof, recently excavated in Hercolaneum (so you can better understand) http://www.antikitera.net/images/imgNews/11636-4.jpg

“Grunda” (italian “gronda”) derivates from Proto-IndoEuropean *ghrend- = “beam, board” “Grunda” generates the verb “grundare”, that means “to drip/pour”.

Like you can see in the picture above, roman roof had a system of gargoyles. So the “(spatium) subgrundarium” was not a very protected space, because it was a “spatium stillicidiarium”.

The roman architect Vitruvius wrote about “extrema suggrundatio” (Vitruvius, II, 1):

1. Trabes enim supra columnas et parastaticas et antas ponuntur; in contignationibus tigna et axes; sub tectis, si maiora spatia sunt, et transtra et capreoli, si commoda, columen, et cantherii prominentes ad extremam suggrundationem (…).

[Translation: 1. Beams are placed on columns, pilasters and responds. In floors there are joists and planks. Under roofs, if the spans are considerable, both cross pieces and stays; if of moderate size, a ridge piece with rafters projecting to the edge of the eaves (…) ].

So I think that if they buried infants “in suggrundariis”, the reason was that corpses, under the action of the rain, could decompose more easily. You could

see religious implications if you want. There are archeological attestations of ancient burials like that…

(…”for example a large eaves tile with a painted meander band preserved in the Antiquarium Comunale, as shown by recent archive investigations, was found in 1883 on the Esquiline covering an infant grave (suggrundium) in a lot southeast of Piazza Vittorio Emanuele andconfused in the first publication with a group of smaller decorative terracottas, actually discovered in via di Monte Tarpeo.”) Another example: “Subgrundarium” as “niche” could be a modern reinterpretation.