Piper at the Gates of Dawn: Pan, Kenneth Grahame and Wind in the Willows April 6, 2015

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackThe golden age of British children’s literature stretched from the last decade of the nineteenth century to the 1950s: in that period men and women of immense talent wrote for their sons, their daughters and in most cases for their atrophied child-like selves. Among these was the sad and sometimes wretched Kenneth Grahame. Like T.S. Eliot this talented Victorian found himself working in a bank (or rather the bank, the Bank of England) and whiled away and wasted many years there before forced retirement encouraged him to write.

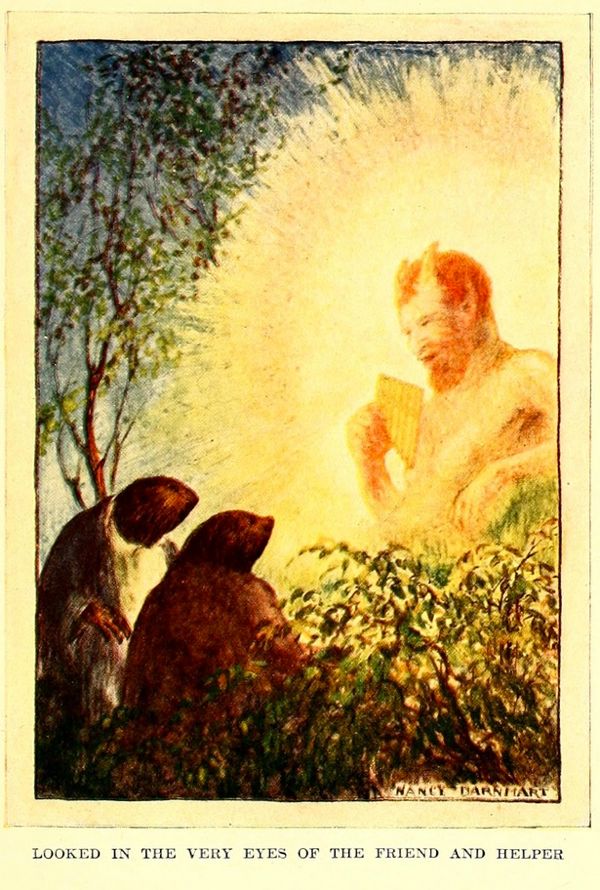

His most famous work is The Wind in the Willows written for his son, Alastair, who ended his teens and his life by putting his head on a railway track. Alastair was the inspiration for Mr Toad… The Wind in the Willows has often been performed on the stage and there are several television films/adaptations, perhaps none so successful as the early 1980s stop-motion series from Thames. However, most adaptations and many reprints of the book miss out its secret heart, chapter seven: The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, one of the most ‘heathen’ moments in modern literature, all the more remarkable for the fact that it is hidden in a book for seven-year-olds.

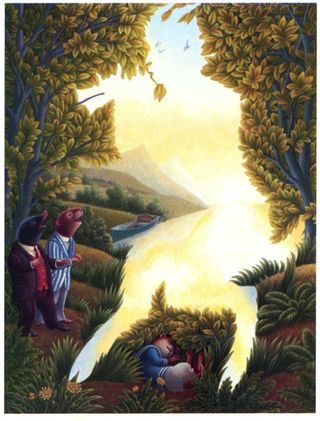

The story is quickly told. Otter has lost his son and Rat and Mole get in their boat and row through the night to look for him. Just before the dawn they come on an incredible music and walking through the trees come face to face with a deity who is clearly (though never named) the Great God Pan. There at Pan’s feet is the lost otter boy. Ratty and Mole wake up later to find the otter boy and Mole is aware of a dream he cannot remember, while Rat notices hoof prints in the grass: Pan has blessed them with forgetfulness. They then load the boy into the boat and take him back to his family recognizing though that they have had an unusual if elusive experience.

The chapter is probably the least known but the most loved part of The Wind in the Willows. It has a cult-like status among many who read it as a child: not unlike the passage describing Galleon’s Lap in A.A. Milne’s Winnie. Grahame had written about Pan before, above all in his rather anemic Edwardian Pagan Papers: ‘In the hushed recesses of Hurley backwater where the canoe may be paddled almost under the tumbling comb of the weir, he is to be looked for; there the god pipes with freest abandonment.’ In The Wind though Pan is virile and benevolent, glorious and secret: in short just what a Greek god should be. For those of us who regret Julian’s passing this tribute from Grahame is something to savour.

Pan appears in other guises in twentieth-century English literature. A sexualized goat god is to be found in the short stories of E.M. Forster. Machen writes The Great God Pan, a flawed (?) but fascinating work. Pan also appears as the god of gnomes in the work of B.B. if memory serves correctly Pan kills a man who has been abusing the animals of the forests. This gaia Pan, very reminiscent of Grahame’s, is not perhaps the Greek ideal but he is impressive. Other moderns Pans: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

There are several musical reflexes of the Piper: Van Morrison, a piece by Andy White (that Beach has come to love) and Pink Floyd’s noisy album.

And here is the central description from chapter seven:

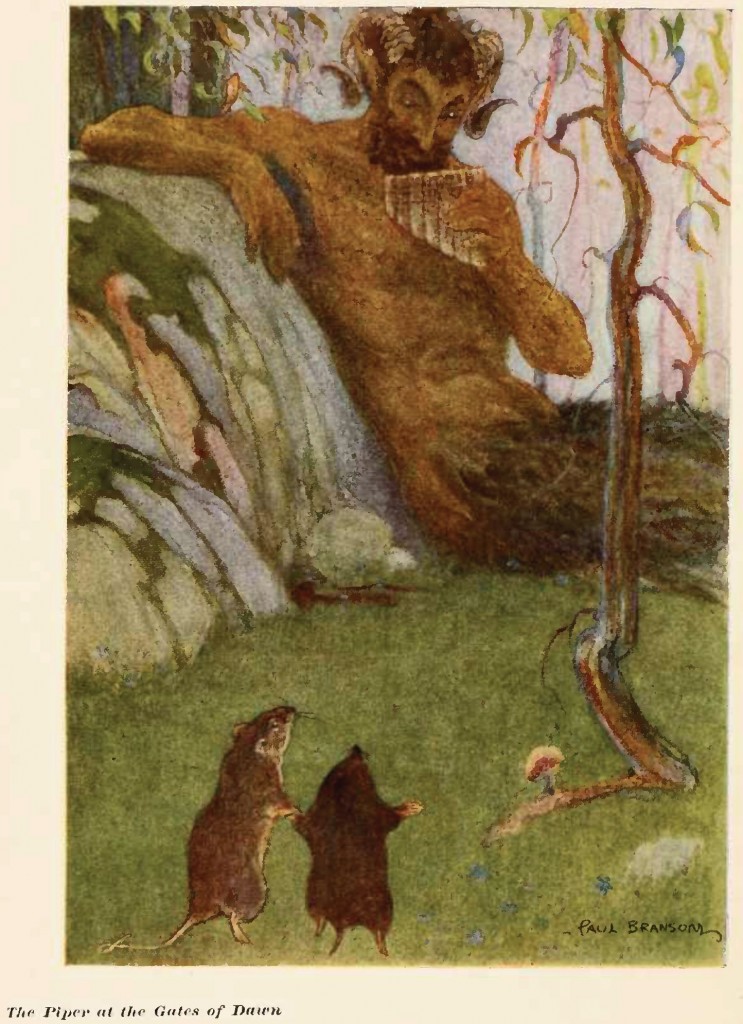

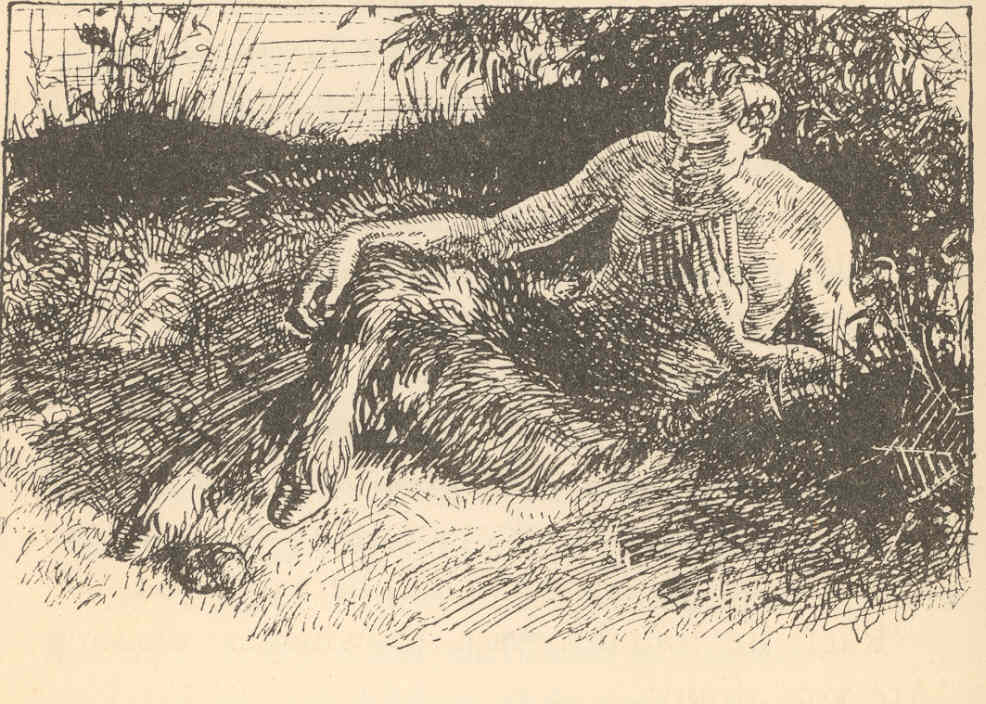

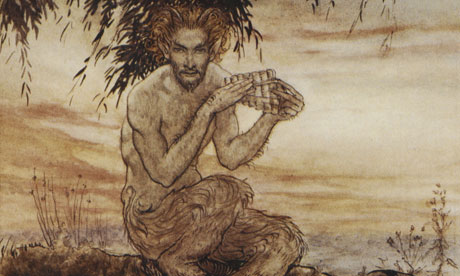

and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fulness of incredible colour, seemed to hold her breath for the event, [Mole] looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humourously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

All images relate to the Piper episode. Look out for baby otter.

30 April 2015: Invisible notes the wonderful Saki story Music on the Hill

31 May 2015: John M, an old friend of the blog writes in, ‘Another interesting rendering of a Pan-like creature is found in Guillermo del Toro’s film Pan’s Labyrinth. I resisted this film for a while, but when I did watch it, I was well pleased. I found it to be a touching story. You might find some interest in it. The director has stated that the faun in the story is not Pan. (The original title in Spanish is El laberinto del fauno.) Nonetheless, it is a captivating fairy tale, well within your bailiwick. Also, I’m not sure it fits into the tighter definitions of modern, but the story does take place in 1944.

28 Jan 2016: Southern Man writes in ‘Reading this story again, it might be worth noting that there was a great deal of Edwardian interest in Pan in the UK: really! E.M.Forster, some lines of D. H. Lawrence. However, to evidence. Richard Stromer, An Odd Sort of God for the British: Exploring the Appearance of Pan in Late Victorian and Edwardian Literature

Evidence of this oddity was first uncovered by Helen H. Law in 1955, with the publication of her extensive bibliography of Greek myths cited in English poetry since Shakespeare. In that bibliography, Law lists 106 citations attributed to Pan, with the next nearest total attributed to Helen at 63 citations and to Orpheus at 61. Studying this list of citations in terms of date of authorship, however, points up an even odder anomaly, namely that nearly a third of the citations to Pan were for works written between 1895 and 1918. Patricia Merivale, in her exhaustive study of the role of Pan in literature from classical times till the present day, not only cites Law’s research, but also attaches particular importance to the spate of Pan-related English prose also published in the thirty-odd year period between 1890 and the end of World War I.

So now you know.