In Search of Medieval Pain February 26, 2015

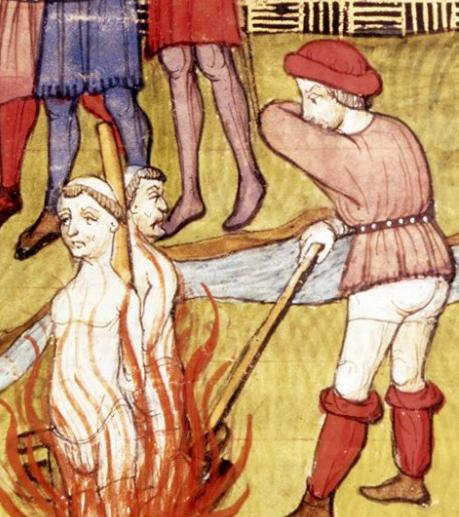

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval , trackbackFirst, a small rider. Beach would prefer to spend ten minutes in the company of medieval artists, than two hours in the company of the Renaissance ‘masters’. However, he has recently been disappointed in a search for pain among his favourite twelfth-, thirteenth- and fourteenth-century painters. In his naivety he thought that crucifixion scenes and scenes of hell would fill his desktop folder with medieval agony in ten to fifteen minutes. Instead, the Middle Ages, a particularly painful period after all, just didn’t seem to approve of expressing pain or grief pictorially, or at least when medieval artists attempted to show pain they generally fluffed it. Take the poor Templars being burnt below (the one on the left has the kind of expression that says ‘Damn I can’t remember where I put the car keys’). Of course, they are supposed to be stoical in the certainty of salvation, but a little agony for the camera, guys… In fact, by far the most successful face here is the executioner endeavoring not to get smoke in his eyes and human fat on his tunic.

Ditto St Sebastian

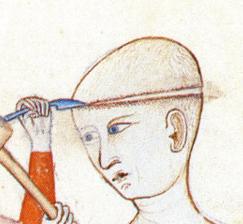

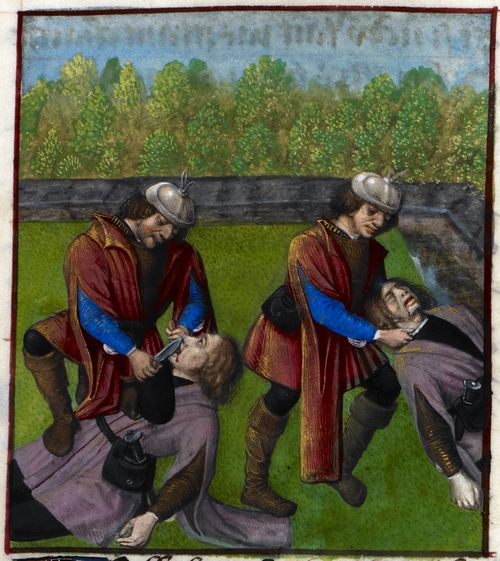

There follows some of the very few painful faces Beach found from Medieval Art, 500-1500 (including medieval-style art from 1300-1500). Let’s start with perhaps the greatest work of medieval art ever made: Giotto’s Christ crucified, today guarded in Borgo Ognisanti (Florence) by some scary Domenican monks: it is at the head of this post. Christian or Muslim, believer or atheist, stand twenty feet from it, look up and your knees will go weak. Here below, meanwhile, going from the sublime to the sordid, is a late fifteenth century art work (perhaps too renaissance-y to be legally included here, sorry) of a man having his tongue cut out. The interplay of the eyes is powerful.

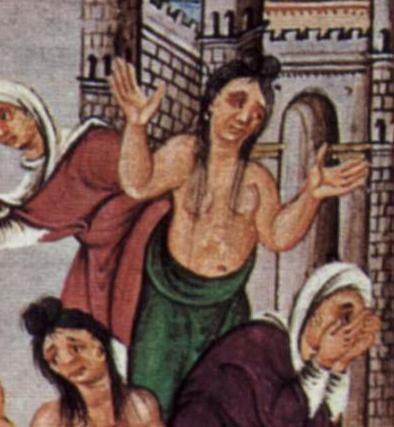

A woman (mid fourteenth century) is about to undergo a surgical procedure here. On reflection Beach would rather have his tongue removed, as long as the knife was sterilized…

This one is a picture any parent will understand. A child has just fallen to the street from an upstairs window and a mother bends over her dead son disconsolate. Note again, though, no running mascara: imagine what a Victorian painter would have made of this horrible scene.

Here, instead, is a man burying plague victims from fourteenth century France. There is something in the expression that suggests infinite misery and perhaps, too, a knowledge that the man in question will soon be below ground with his loved ones.

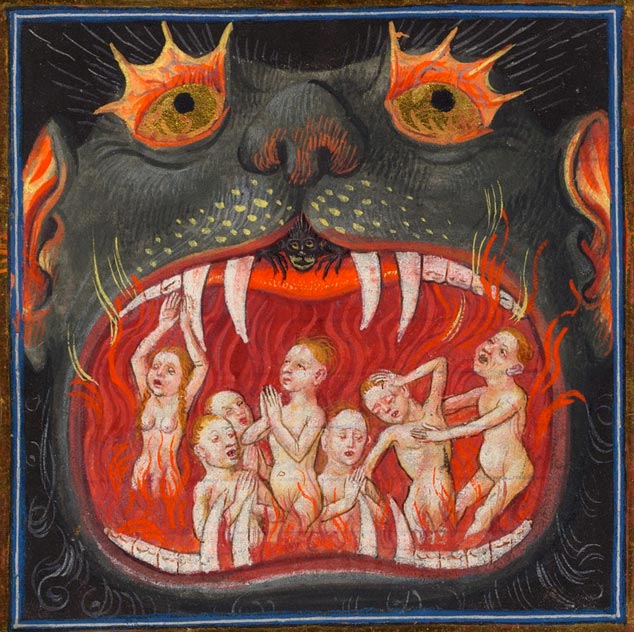

Finally, here is a slapper at a party in hell. She doesn’t seem to be enjoying herself. Many hell scenes show rather apathetic guests: perhaps there is the idea that they have got used to the pincers and teeth? This woman would definitely prefer to leave…

All the full pictures are below so the pain can be ‘enjoyed’ in context. Any other medieval pain: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

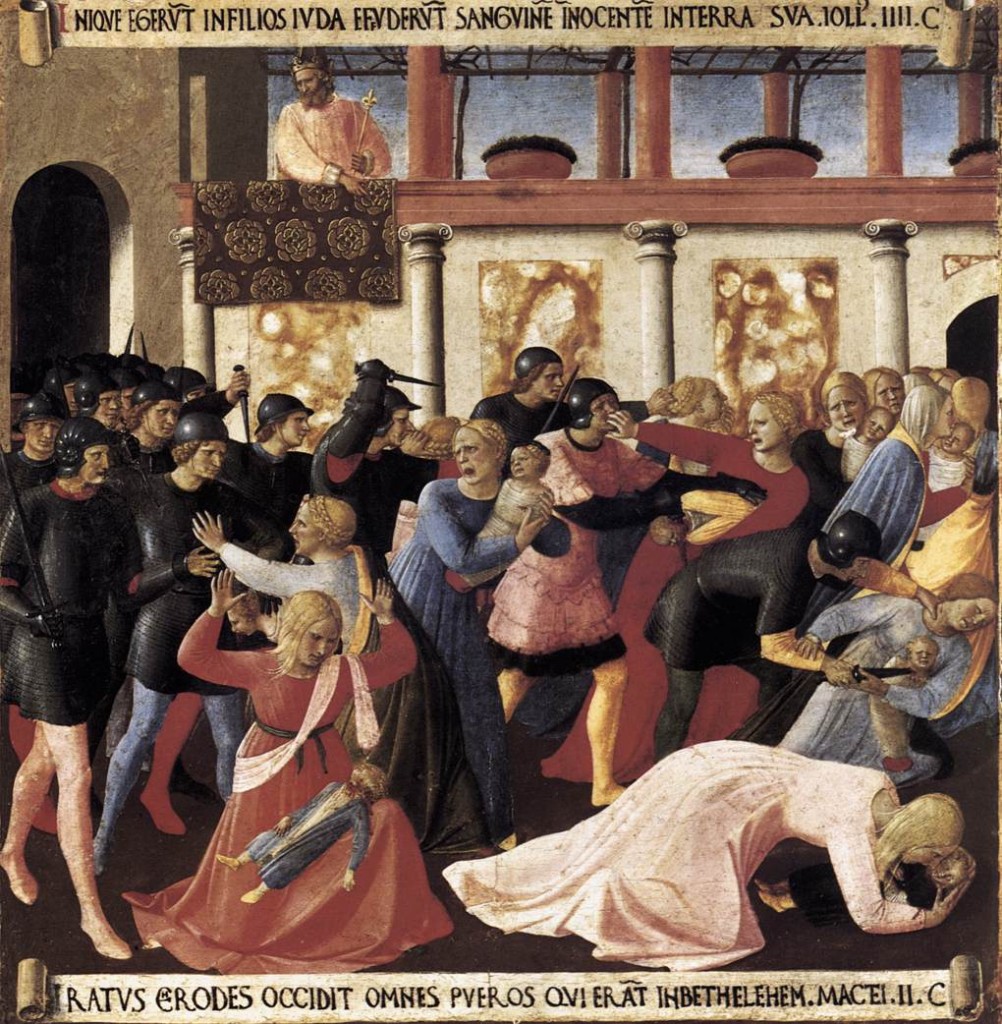

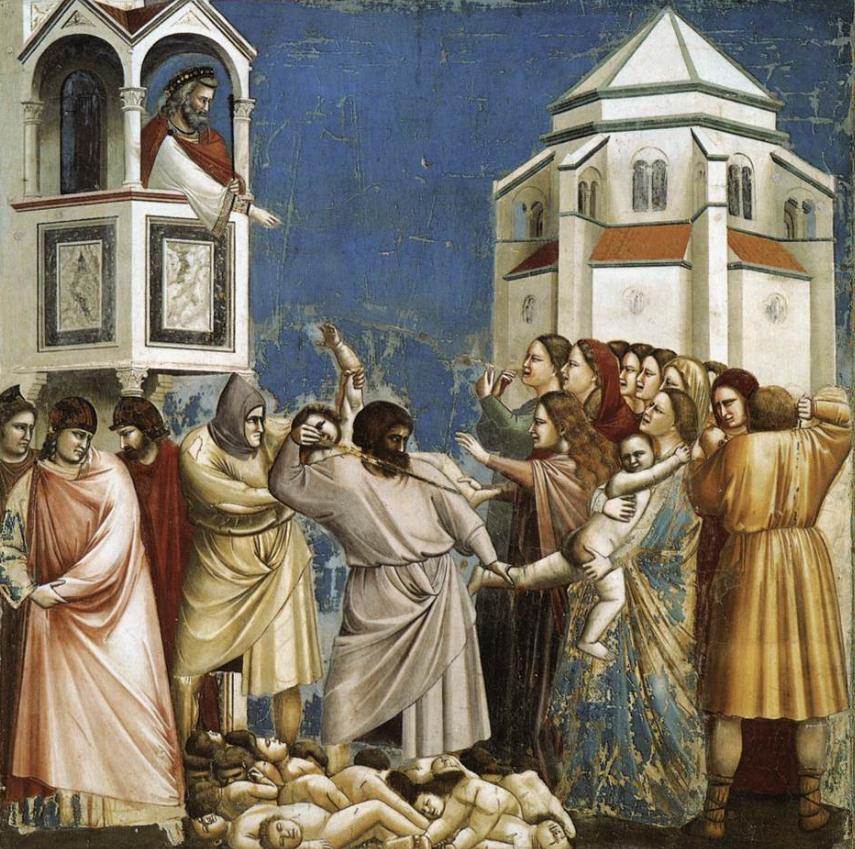

26 Feb 2015: Chris sends in some fabulous images. I’ve done the close ups and added them below. First Giotto slaughter of the innocents

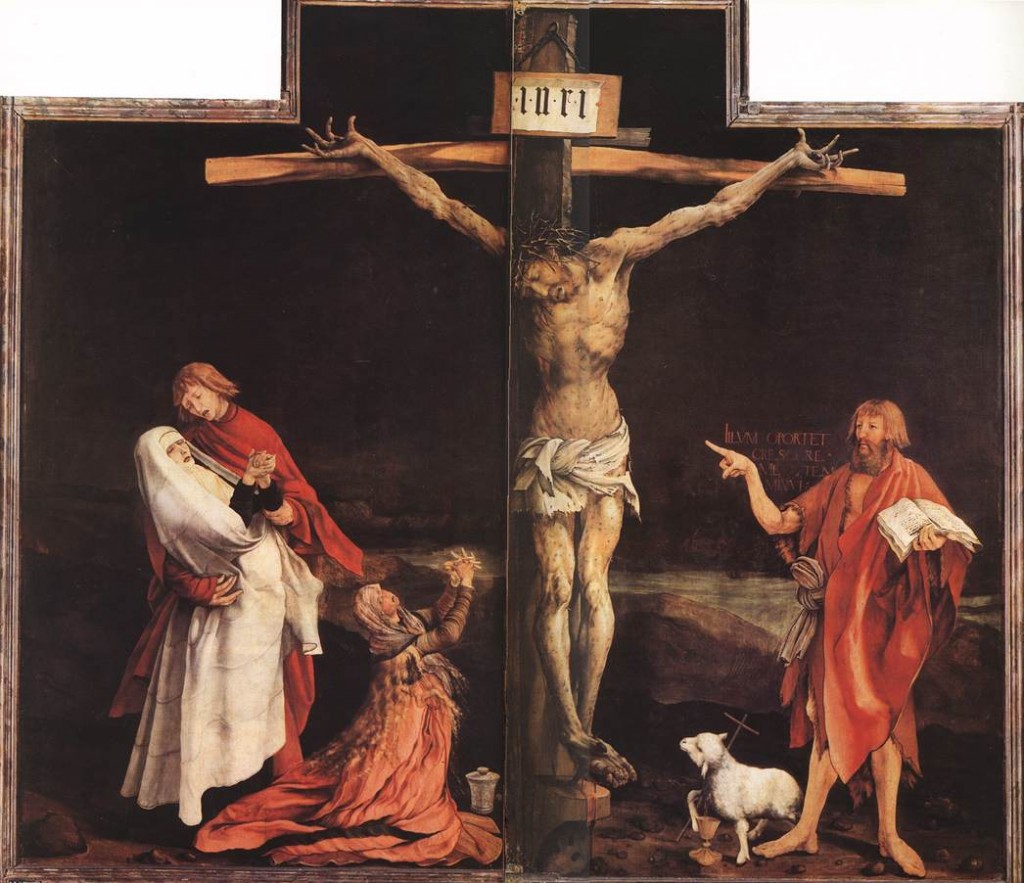

Matthias Grünewald’s Mary

Egbert Codex: massacre of the innocents

The great Beato Angelico and his massacre

Invisible, 30 mar 2017, send this in. Looks like it may be a good read.

Item Number: 144848

Title: The hurt(ful) body : Performing and beholding pain, 1600-1800

Author: Macsotay, Tomas (et al)

Price: $110.00

ISBN: 9781784995164

Record created on 03/16/17

Available September 2017

Description: Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017. 24cm., hardcover, 368pp. illus.

Contents: 1. Spectacle and martyrdom – bloody suffering, performed suffering and recited suffering in French tragedy (late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries), Christian Biet. 2. The Massacre of the Innocents – infanticide and solace in the seventeenth-century Low Countries, Stijn Bussels and Bram Van Oostveldt . 3. To travel to suffer – towards a reverse anthropology of the early modern colonial body, Karel Vanhaesebrouck. 4. ‘I feel your pain’ – some reflections on the (literary) perception of pain, Jonathan Sawday. 5. Masochism and the female gaze, John Yamamoto-Wilson. 6. Epicurean tastes – towards a French eighteenth-century criticism of the image of pain, Tomas Macsotay. 7. Wounding realities and ‘painful excitements’ – real sympathy, the imitation of suffering and the visual arts after Burke’s sublime, Aris Sarafianos. 8. Forced witnessing of pain and horror in the context of colonial and religious massacres – the case of the Irish Rebellion, 1641-53, Nicolás Kwiatkowski . 9. Theatrical torture versus dramatic cruelty – subjection through representation or praxis, Frans-Willem Korsten. 10. Palermo’s past public executions and their lingering memory, Maria Pia Di Bella. 11. The economics of pain – pain in Dutch stock trade discourses and practices 1600-1750, Inger Leemans.