The Mystery of the Fairy Battery January 5, 2015

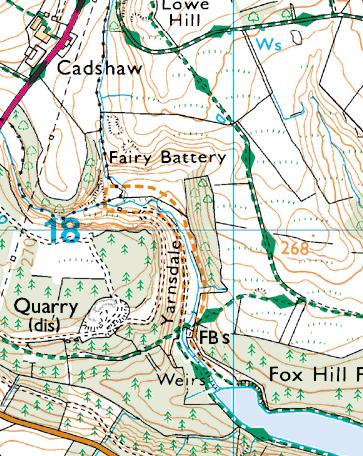

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary, Modern , trackbackHere is a place and a name that is hard to account for. On the 1850 Ordinance Survey map for Lancashire (79) there is a peculiar rock formation with the words Fairy Battery by the side. This is on Lowe Hill to the north of Turton and Entwistle Resevoir (already built in 1850). There follows the 1850 map and a modern map of the same thing. These outcrops are apparently famous in climbing circles and they often appear on the internet on climbing blogs as Cadshaw Rocks or Cadshaw Castle Rocks. One of these climbing sites alleges that they are also known as the Fairy Buttery. (It might be noted here that climbers seem to be mainly responsible for the change in nomenclature: if any of the brotherhood of the carabiner are reading this please revert to the original, England has many too many Rocks and too few fairy names.) A number of sources claim that in the seventeenth century this was a secret place of worship for non-conformists. It is certainly out of the way and it would be easy to post sentinels there.

The mystery is what is meant by battery, always assuming that it is not buttery mispronounced. Well, battery does occur in English placenames, but it is usually associated, as we would expect, with a gun platform. For example, there is Liscard Battery built in the mid nineteenth century, on Merseyside that guarded Liverpool (against what?!). There are a number, though, of more doubtful names. Take, for instance, Oliver’s Battery, in Hampshire, a hill-fort associated, on good grounds, with Oliver Cromwell and the Roundheads. Did the Parliamentarians have a gun encampment there? It seems almost impossible that fairies would be associated with artillery, though it would be more likely in the nineteenth century than in the twenty-first century. But what else could battery mean? The long Oxford English Dictionary gives no help here, unless there is just possibly a reference to a battery of fairy drums. Joseph Wright’s Dialect Dictionary is more helpful. He gives ‘a sloping wall, an embankment’, and as ‘a butress’. These meanings are associated with Ireland, Northumbria and the south-west. But they are widespread enough that it would not be that suprising to see this sense of the word in Lancashire. If so we would have the fairy walls or the fairy buttresses, presumably guarded by a regiment of little folk. Was it used in a jokey way, by locals, perhaps those early Baptists fleeing the wrath of the established or Catholic Church? Or was it used in sincerity as the visible and defended part of a submerged fairy city?

Any other help with the fairies battery: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

6 Jan 2015: Mike Dash writes in with this: Could it not be that this rather striking shaped rock formation got its name simply because it looks like a gun platform – large, flat, and apparently built into the side of a hill? While it certainly could be that the district was associated with a fairy tradition, it might not be necessary to suppose anything so concrete as a tradition involving the visible to-parts of an underground city; the naming might be more whimsical than that. As for what the nineteenth century battery at Liverpool was defending against, the answer is actually obvious, if apparently ridiculous at this perspective – it was there to prevent French raids, or perhaps a French invasion. Memories of Napoleon’s quite serious intentions to invade (and the farcical French invasion of Fishguard in 1797) lingered for quite a while, and were exacerbated by French naval advances from the 1840s. The French were the inventors of the shell-gun in 1841, but most obviously they threatened Britain with the construction of the Gloire, the first ever ironclad warship, which coincided with the completion of the new defences at Cherbourg – giving France, for the first time, a secure deep-water port on the Channel from which to launch an invasion. This was the first modern “arms race”, and there were serious war scares involving France in 1840 and 1858 as a result. Certainly the idea of a raid on shipping using these new wonder-weapons was not incredible, but nor, in the eyes of those around at the time, was a full-blown invasion completely out of the question – it was generally assumed that Britain’s enemies would decoy the Royal Navy away by arranging for some spurious foreign crisis, and the idea was often pushed by army interests as it would have meant diverting some of the (always scarce) defence budget away from the navy and into more troops and more fortifications. C.I. Hamilton’s Anglo-French Naval Rivalry 1840-1870 is the key text here.

Neil H, meanwhile: The Lancashire Evening Press says the earlier name was Pulpit Rock. http://www.lep.co.uk/news/walking-entwistle-reservoir-1-63840 There is no mention in The Place-Names of Lancashire by Eilert Ekwall, Ph.D., Professor of English in the University of Lund (1922). Ekwall was the doyenne of place name studies, though more interested in Skandinavian and Early Englishsources than folklore. I suspect he would have regarded an 1850 OS map as too recent to be of interest. http://archive.org/stream/placenamesoflanc00ekwauoft/placenamesoflanc00ekwauoft_djvu.txt Ekwall noted p.261 6. Folk-lore, etc. Only a few isolated names contain allusions to popular beliefs or customs. Of interest are names containing O.E. pyrs ” giant, goblin ” (Thirsden, Thursclough ; cf. Thuresdoch CC 647, in Hindley) or O.N. purs the same (Thrushgill, etc. ; cf. p. 182). The words, as will be seen, are always combined with such words as mean “a ravine” or “a fen” Alden may contain O.E. celf, ielf, “a fairy.” On Grimshaw see p. 76. Dragley apparently means ” the dragon’s mound,” and may refer to some local legend. Cf. Also Drakeholm, p. 253. For Cadshaw p.261 he has: Cadshaw (Higher and Lower) : Kaddehou, Cadeshoubroc, Cadeshouclou, Cadehouclou c 1200 Whit. II. 400, Cadshawe 1617 Blackburn R. Sometimes written Cadger and pronounced [kadza]. The places are on the brow of a hill, near abrook. The elements of the name are the O.E. pers. n. Cada and O.N. haugr “hill” (or possibly O.E. hoh), later associated with shaw.LEME, which is a much better source for early modern English than OED, has two interesting entries: http://leme.library.utoronto.ca John Florio, Queen Anna’s New World of Words, (1611); Scazzambrello a Hobgoblin, a {s}prite of the Battery, a Robin good fellow. I have no idea what a “a {s}prite of the Battery” means unless it is a sprirt living in rocks. You may have better luck with Scazzambrello in Italy. One source uses the words “spirito della casa”. Other sources have: 1598 FLORIO. (Also s.vv. pkantasma, larua, scazzambrello.) “Herbaut. The name of a merrie Diuell, or Hobgoblin, that appeared most commonly on horsebacke.” The earliest entry in LEME which (possibly)uses Battery as a formation like a bastion is:- Guy Miège, A New Dictionary French and English, with another English and French (1677) Terrasse (f.) a Terrass, or stone-Gallery raised from the Earth. Terrasse, pour placer le Canon, a Battery. Terrasse de Bastion, de Citadelle, sorte de Fortification, the Terrass of a Bastion or Cittadel.