Roman Coins in Iceland December 16, 2014

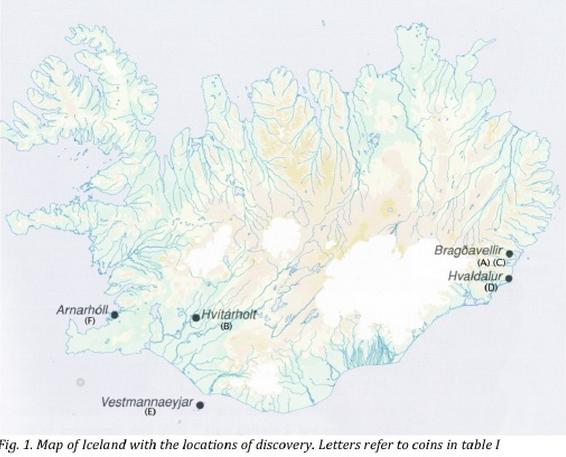

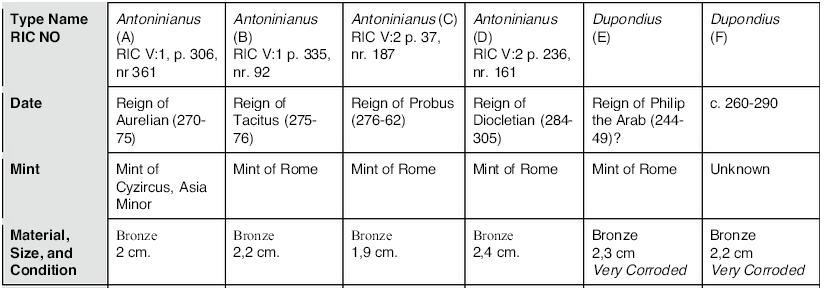

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Medieval , trackbackRoman coins have been found within and without the Empire. Denarii and solidii turn up in Scandinavia, Free Germany, Ceylon, Mainland India and Ethiopia, there is even one fascinating outlier in Madagascar (another post, another day). These coins will have arrived in two separate ways. Some will have been brought by Roman traders and some will have been passed from hand-to-hand from those traders or barbarian visitors to the Empire into the wildlands beyond. However, five Roman coins in Iceland (included here on a map from David Haidarsson’s excellent thesis, the bedrock of this post) are in a slightly different category. The problem is that in the third century when these coins were minuted there was, to the best of our knowledge, no inhabitants on Iceland. Seen in that light Roman coins in the proud island are far more strange than a Roman coin in Madagascar or, for that matter, Congo (where another Roman coin turned up in unlikely circumstances). There is some very inadequate evidence for temporary visits from Irish monks in the sixth to ninth centuries, and there may be some small hints for other transitory (fishing) populations but nothing approaching evidence for permanent settlement before the Vikings shouted ‘land ahoy’ in the late ninth century (for comparative evidence from Faeroe follow this link). So what were the coins doing there?

Crudely speaking there are two possibilities. The first is that they were brought to Iceland in Roman times; the second that they were brought after the collapse of the Western Empire, either in the sixth or, say, the sixteenth century. A Roman visit to Iceland is not in itself impossible. The Romans recognized a land to the north of Britain called Thule and this might very possibly have been Iceland to judge by Ptolemy’s reference. But there are two big problems with the Roman explanation for these coins. (i) we are talking about multiple rather than single visits given the spread of the coins (or some mechanism by which coins from a single visit were spread around) and (ii) why would Romans even take coins out of their pockets in Iceland given that there was no one to trade with? It might also be worth adding that Roman visits to ultima Thule may have been an imperative of the Roman policy of exploration and mapping in the north: but that regular trips to Iceland would have been made more difficult given that what is today Scotland, Orkney, Shetland and Faeroe were all, essentially, hostile territory.

The second possibility is that someone else brought the coins to Iceland after the collapse of the Empire. Candidates have included the Vikings, the Irish monks who came to live hermit lives in Iceland and modern fakers like mad coin-burying Halliday. Modern fakers may have been responsible for a couple of the coins, but the spread of five means either five different fakers or a very systematic single faker. Note too that one of the coins was found by a noted Icelandic archaeologist at a Viking site: Thor Magnusson. And, in fact, the best explanation is given by the Vikings – we’ll leave coin-collecting Irish monks to the side… – bronze Roman coins have been found in early medieval and Viking age Scandinavian sites, where they seem to have been recycled as currency. Bronze, after all, has a basic value whoever’s head is on the coin… (Victorian sovereigns may not be legal tender, but their gold value means that they are still valuable: readers gathered many other examples together in a previous post.) There would be nothing strange about Vikings bringing some of these coins to the west with them, using them as small change for chicken trades…

The one last thing to note is though that the five coins cover a relatively short range: one that is as narrow as forty years. Did the Icelanders see an influx of Roman bronzes from a hoard then? There may be a small outside chance that this hoard was found on Iceland itself, though surely Britain or northern France would be a better bet? Note that the table again is from David Haidarsson’s excellent thesis. The conclusions here shadow, in most respects, his own. Thoughts: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

16 Dec 2014: Lehmansterms to the rescue! You knew I wouldn’t be able to let this subject go by without comment. For whatever this information may be worth, the Icelandic Roman coin finds belong to 2 distinct periods – although the periods were sequential, the dupondii – of which 2 were found – would have gone out of circulation about 5-10 years before the first of the Aurelian antoniniani entered circulation. When the Antoninianus – which was originally pretty good silver when Caracalla decided to use 1 1/2 denarii-worth of silver to create a double-denarius – had finally become so debased that there was no longer silver enough in the alloy to make the coins appear silvery – approximately 260 – they were, for all practical purposes, no more than bronze with a tiny admixture of silver (2-5%). At that point the dupondius – a substantial brass or bronze coin weighing approximately 10+ g which was used in making change at one-sixteenth the value of the antoninianus – no longer made any sense and disappeared from circulation altogether. Mainly re-cycled as the c. 2.5g antoniniani by official and unofficial mints alike, the circulating dupondii and sestertii were an artifact of a now defunct economy in which at least the appearance of silver was maintained in the major circulating coin. Aurelian made a brief and abortive attempt to re-introduce a heavy bronze or brass piece as a part of his economic reforms c. 272. It was a bit bigger than a 2nd century dupondius, smaller than a sestertius. It’s unclear whether this piece was meant to be a sestertius or dupondius, but it was introduced before its time and as such was an instant failure. They are quite scarce today. You might say this financial phenomenon was very similar to a time like the mid-1960’s in the US when the formerly current 90% silver minor coins were all replaced by cupro-nickel. Greshams Law was seen in ferocious action by all of us who remember the time. There was an instant coin shortage as soon as the CuNi coins appeared c. 1964/5 as the silver was vacuumed out of circulation at a frantic rate – far quicker than the new coins could be produced and distributed. The dupondius disappeared “overnight” from circulation not unlike the US silver quarter-dollar because it was worth a good bit more as bullion than its nominal value.