Punishing Suicide August 24, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackIf you attempt to commit suicide today (and you survive) you will be treated with sympathy by your family and friends: if the state interests itself in your case it will be to offer mental health assistance or to prevent a repetition by some other means. The contrast, in the UK and other common law countries, with a century ago, when suicide was a criminal act is notable. An example taken at random: Annie Kelly (54), a Liverpool laundress was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment in Chester in World War One after trying to kill herself (1 July 1918). We live, of course, in a world where people are stoned for changing religion, drinking or adultery (real or imagined) and it takes a lot to shock us: but by modern standards this kind of sentence is jarring, not least when you consider how difficult it is to get a year inside in many western countries.

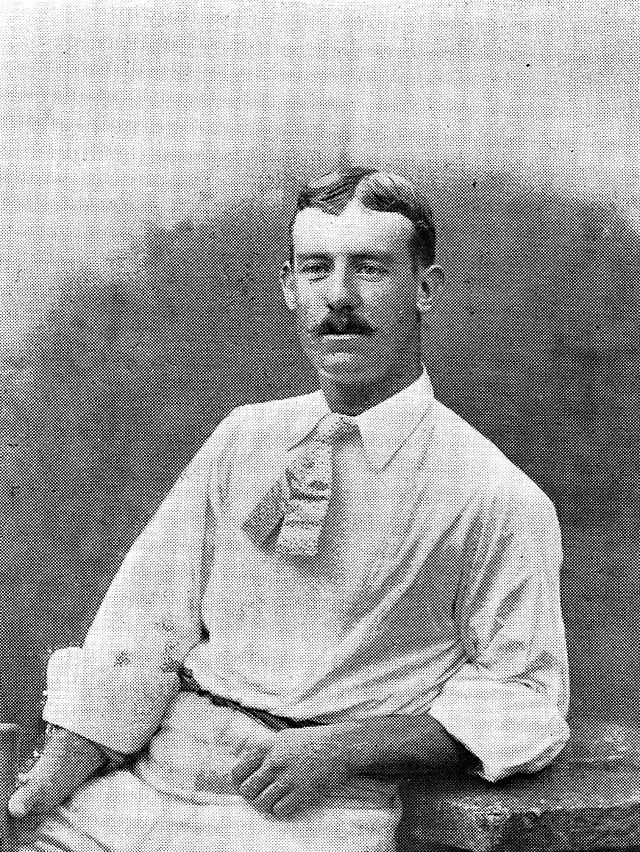

However, the Victorian and Edwardian courts did not always use prisons as a solution to suicide. Anyone who has ever spent time looking at nineteenth-century or early twentieth-century court records will have noticed how, far from our crude stereotypes, judges and juries were often surprisingly considerate towards vulnerable suspects. This was done in various ways for suicide. Often the fiction that there was no proof that the act was a suicide was allowed to derail the prosecution’s case. Take, for example, the girl (Kate P. Savage 18 May 1889) who jumped off the cliff after an argument with her mistress. Did she jump or did the wind perhaps blow her off? Choose the latter and the problem goes away. In other cases a jury found a prisoner guilty but the judge would ‘discharge to friends’, instead, of giving a custodial sentence: in other words friends would be given the responsibility for looking after the suicide attempter in a period of recovery. This was the ‘punishment’ given to a Yorkshire cricketer Billy Bates (pictured above) when he attempted to commit suicide in 1889: he had been depressed at having been told he would never play cricket again because of an eye injury. (He died ten years later of a cold). In other cases prison sentences were given: sometimes it was because suicide had accompanied another crime (man tries to kill himself after murdering father etc etc); sometimes it was because the judge believed there was need for a punishment; but in other cases the prisoner was placed in prison at his or her own request (in two cases in preference to workshouses, e.g. Ellen Turner 4 July 1890). Perhaps prison was sometimes preferable to going back to the daily grind that had brought you to despair: not therapy but a space to think without having to make too many decisions?

There were cases where a severely tested judicial system made extraordinary efforts to protect prisoners by giving them the benefit of the doubt. Take Mary Anne Payne, 21 who, in 1863, while four-months pregnant, took her son’s life by dosing him with laudanum and then cutting his throat; she then attempted to cut her own throat and, then, when she could not go through with it, jumped from a window onto the street below, though she survived. Beach knows early modern legal records quite well and back in the 1600s Mary would, in most European countries, almost certainly have been executed and probably in a pretty horrible and very public way. As it was the jury found her not guilty for this horrible crime by reason of insanity and she was confined, which would have meant a state asylum (where things could have gone brilliantly well or horribly wrong), our equivalent of diminished responsibility.

Are there any country’s in the world today where suicide is still punished? Are there any records of attempted suicide being punished by death? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

31 Aug 2014: Ricardo writes that in Portugal suicide is still a crime (as suicide assistance, as in many countries) Mike L writes: Many of old Victorian laws still subsist in India and Singapore. See below. I can’t find any corroboration for the statement about Japan. Section 4 of the Indian Penal Code is interesting – it would seem that an Indian citizen attempting to commit suicide, say, in the UK, is still liable under Indian law and could be prosecuted in India (and extradited from the UK to face trial?) The Indian Penal Code 4. Extension of Code to extra-territorial offences. — The provi¬sions of this Code apply also to any offence committed by — [1] any citizen of India in any place without and beyond India; [2] any person on any ship or aircraft registered in India wher¬ever it may be; 309. Attempt to commit suicide.— Whoever attempts to commit suicide and does any act towards the commission of such offence, shall he punished with simple imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year, or with fine, or with both. “In the Hindu religion, if a person under the influence of passion or anger, or a woman infatuated by sin, commits suicide by means of rope, a weapon or poison, he shall be dragged with a rope on the public road by a ‘chandala’. There shall be no cremation rite for them nor obsequies by kinsmen. Any relative who performs funeral rites of such person shall meet the same fate afterwards and shall be abandoned during his life time by his kith and kin. Whoever associates himself with such persons, or who performs forbidden rites, shall forfeit within a year the privileges of conducting or superintending a sacrifice, of teaching and of giving or receiving gifts, as shall others having dealings with these.” [V.K. Gupta: Kautliyan Jurisprudence p. 25. Japan: Committing suicide is considered illegal, but it is not punishable. Singapore Penal Code (CHAPTER 224) An Act to consolidate the law relating to criminal offences. (Original Enactment: Ordinance 4 of 1871)(Previously The Indian Penal Code 1860) REVISED EDITION 2008 309. Attempt to commit suicide Whoever attempts to commit suicide, and does any act towards the commission of such offence, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year, or with fine, or with both.