Review: The Adventures of Hergé August 6, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackGeorges ‘Hergé’ Rémi (obit 1983) was an exceptional draughtsman who published, between 1930 and 1976, twenty three comic books that contained the essence of the short twentieth century. It was all there: continental totalitarianism, arms dealing, South American dictatorships, the death of colonialism, the Cold War, Arab nationalism, the internatonal drug trade and the battle for petroleum; even the Yeti and UFOs make brief appearances. Someone born in August 2014, who, in later life, will decide to become a historian of the 1930s, say, could do far worse than read Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin repeatedly. They would do so not just for the art, not just for the characters, not for the crass Benny Hillyism of the early books, or the awe-inspiring comic routines of the later volumes, but for the history that sweated from Hergé’s fingers when he dipped his pen in Indian ink.

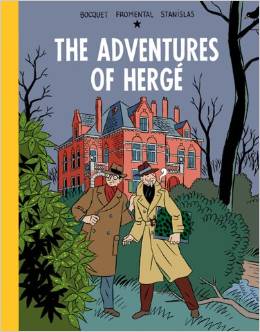

Several biographers have taken a run at Hergé, a Catholic Walloon with a penchant for boy scouting (as opposed to boy scouts). The most compendious is Assouline’s Hergé, the easiest to take in is Harry Thompson’s Tintin. But in 2007 a new rival came on the market, one that has been available in English for the last three years, Bocquet, Fromental and Stanislas’ The Adventures of Hergé. The authors had the brilliant idea of presenting Herge’s life in the format of a Tintin comic with the iconic front cover and the Tintin type and comic strip inside spread over sixty six pages. This is easy on the eyes – the artwork is lovely – but also jarring: there is something subversive in seeing Andy Warhol or a nude woman in the chaste Tintin format, the equivalent of reading the American constitution in Curlz or the Lindisfarne Gospels in Garamond. The authors also eschew the steady realism of Tintin (comic book realism that is) and the book occasionally dips (successfully) into the magical rhythms of REM.

This is no pretence at a complete biography: how could it be? Rather Herge’s life is given in episodes that last four to six sides. For someone who knows the canon the result is affecting. Hergé life is seen through the filter of Tintin and episodes in his life are made to ape, graphically, familiar scenes from the Tintin books. Sometimes the ‘copying’ is so blatant, indeed, that Beach found himself wondering whether the Hergé Foundation didn’t have something to say in terms of copyright. The HF probably decided to let things go as the book should only add to Hergé’s reputation. Not that it is hagiography. Hergé was, as the book shows all too clearly, a decent, not particularly courageous Walloon who made a couple of quite bad and some very good decisions over difficult years for his country, including the recovery from the First World War and German occupation in the Second. Memorable scenes include: a Belgian patriot begging Hergé not to publish in a collaborationist newspaper; Hergé reuniting with Chang (symbolically the most important friendship of his life); and the final scenes in an airport of dreams.

And if you do not know Tintin? This is not the book to start an acquaintance with Hergé or his canon: it is the natural end not the beginning of any relationship. But if you don’t know Tintin you have other books to buy. The early Tintin volumes are period pieces, poorly drawn and poorly plotted: several should never be placed in school libraries or, unsupervised, in the hands of children e.g. Tintin in the Congo. But there are other books – Tintin and the Picaros, Tintin in Tibet (Beach’s favourite), The Castafiore’s Emerald (the greatest comic book ever written?), even Flight 714 and the Calculus Affair – that are ‘not for an age but for all time’. They are quite simply masterpieces. If you have not read these then take a day off work, build up the fire with dog-eared copies of Asterix and settle down for a rare treat of narrative, Captain Haddock and Hergé’s vanishing but all too familiar world.

Other unusual books: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com