Irish Colony in Medieval Spain!? July 24, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Medieval , trackback***Thanks to Invisible for this piece***

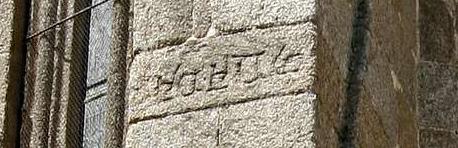

Not every day brings with it really bizarre history, but here is a cracker. An American and a Galician scholar, respectively, James Duran and Martín Fernández Maceiras have gone on record as claiming that a mysterious fourteenth-century inscription on a north-western Spanish church (Betanzos, Galicia) is Irish. Now really that, in itself, would be interesting but not world-changing. Galicia’s Santiago di Compostela was Europe’s premiere pilgrimage site after Rome (with nicer people to boot) and Irish pilgrims were included in the general flow: we have archaeological proofs in the Galician pilgrim shells brought home and buried in Irish graves. However, the two academics responsible for bringing this inscription to light make bolder claims: (i) (as noted) the text is Gaelic (aka Irish); (ii) the word is ‘An Ghaltacht’ meaning the ‘Gaelic-speaking area’; and (iii) the northern fringes of Galicia were Gaelic-speaking as late as the fourteenth century! This is radical, a bit like claiming, say, that the Iroquois settled thirteenth-century Norway unnoticed. Is it credible though?

Well, some background to try and put the following discussion in context. First, Galicia has had, since the nineteenth century, an obsession with its supposed Celtic past. This is not the place to defend or offend the word ‘Celtic’, let alone to do so in a Galician context. But it is enough to say that a Celtic identity has been an important part of modern Galician identity in the struggle facer a patria, to make the homeland. Make no mistake this is a charged issue! Second, there was a well attested medieval British-Celtic settlement in the province of Lugo, very close to Betanzos (Betanzos is in the north-west of Galicia), a settlement that almost certainly began in the fifth or sixth centuries. There are traces of personal names (well certainly one and maybe two) and some Latinate placenames that refer to British populations in the area. There is no question then that medieval population transfers between Britain and Ireland, on the one hand, and Spain on the other, are possible. But how good is the evidence at Betanzos? There are several problems. However, it should be remembered that I’m relying here on a newsreport that sometimes mangles academic reasoning.

(I) as the two profs themselves note epigraphic experts need to properly assess the reading – this means presumably that they’ve gone public after what was a private or a semi-private decipherment with no publication in a peer-reviewed journal. There is a long history of scholars getting inscriptions wrong or sometimes imagining inscriptions where there were none: it is not impossible that there has been an error here, particulary given that neither are epigraphers, nor for that matter fluent in middle Irish. The only photograph online is of low quality (no criticism of the profs this, just the choice of the newspaper that published the story) and it would be important to get a much closer view. [see link at bottom of page for better pics]

(II) I don’t know of another case of Gaelic being written in inscriptions outside Britain and Ireland: there are some ogham stones in Wales, what became Scotland, and possibly a piece of Irish ogham from the post-Roman phase at Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester). The only Irish graffiti we may have on the continent are personal names at early medieval pilgrimage sites.

(III) ‘an ghaltacht’ sounds modern. Gaeltacht is, in fact, the Irish state’s term for Gaelic-speaking areas in the west of the country. The first occurrence in the Oxford English Dictionary dates to 1926. Of course, the word might date back earlier in Irish literary history, where the OED rarely goes. I’d like to see that evidence though… (BTW gaeltacht is often translated as Irish-speaking area and the profs seem to understand it as such. There is no linguistic reference though in pure etymological terms: it is ‘Gaeldom’, i.e. it is ultimately ethnic. And, for the record, no fourteenth-century carver would have chosen language over race.) [see comments of Vox Hiberionacum below on the suspect form, the word as given seems wrong]

(IV) Let’s play ball. Let’s say the text does say Gaeltacht (or a medieval equivalent). Can we really presume that there was an Irish-speaking population in the area on the basis of this text? If the word ‘an ghaltacht’ proves a credible medieval form wouldn’t the easier explanation be that a group of Irish lads turned up and put up the carving after a raid or a drunken night out: ‘we own you’? Given this rather simple solution all the struggle to prove the existence of an Irish community where no one would expect it, seems rather, well, besides the point. [for a more convincing hypothesis see Invisible’s comments below]

(V) we have tolerable number of medieval documents from Galicia and even from the northern fringes of Galicia in the province of Lugo: charters etc. There is not a single piece of evidence for Irish place-names or personal names: and there are now two Galician prosopographies. Placenames and personal names are not ever a certain guide to language spoken, how many English speakers are called Mohammed? But they work as a rule of thumb. They worked, in any case, with the British settlement in Galicia. The British settlement also, as noted above, left behind it many Latin-placenames signaling the presence of ethnic Britons: e.g. Britonia. Again there is no Scottonia or any other Irish equivalent.

(VI) if there was indigenous Gaelic spoken in northern Galicia we need to ask where it came from. Either there was an ancient ‘Gaelic’ settlement dating back perhaps to pre-Roman times: but one which stayed in touch with Ireland (or perhaps preceded Ireland), otherwise the credible Gaelic form is impossible to explain. Or we have to imagine a medieval settlement with a great deal of contact with the homeland: the drift between Breton and Cornish say over just five centuries gives some sense of how languages diverge, even when there is that contact.

(VII) we also have to accept an anomaly like Gaelic-speakers in Iberia not being once noted by a geographer or a medieval commentator from Iberia. The early Middle Ages seems to have had something of a blindspot for languages: but it is very difficult to imagine a thirteenth- or fourteenth-century Galician writer, say, being so uninterested in such a curiosity. It is simply impossible, meanwhile, to imagine a patriotic Irish writer, who had come to hear of the colony, letting this material go. The medieval Irish were mad for such stuff and had no sense of modesty when they could people the world or history with Gaels: the Roman soldier who pierced Christ’s side was Irish according to the Gaels and Simon Magus was an Irish druid on a sabbatical. Again the contrast with the British Celts in Galicia is interesting. They were noticed even in a period with little documentation.

The unwinding of this mystery will prove fascinating, but I would bet Drs Duran and Fernández Maceiras a very big plate of pimientos de Padrón that the Galician Gaeltacht will not be entering the text books any time soon: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

PS a final thought. I wonder if this is not part of a campaign to claim the early medieval British-Celtic settlement as being ‘really’ Irish. If so there are two huge problems. First, the constant application of ‘British’ by Galicians in the Middle Ages; and second the presence of the unmistakably British-Celtic personal name Maeloc (not Gaelic!). It is true also that Galicia appears in the Irish book of origins, Lebor Gabala, but then so does Palestine, Egypt, the Black Sea…

PPS Just finished writing this when I stumbled upon the official page of this discovery in English. I stand by the arguments above. The reading is a brave one, but several of the letters are incomplete or missing…

24 July 2014: Invisible writes in with an interesting point. Is it possible that, always accepting the doubtful reading, the sign meant: Gaels welcome here, or, noting the controversy over language above, Gaelic-spoken here? Betanzos is the natural port for any Irish pilgrims heading south to Compostela. Thanks Invisible!

24 July 2014: Vox Hiberionacum wrote on twitter yesterday (thanks to DB for the heads up): ‘People of the Interwebz: It has come to my attention that the ’14thC Gaelic Inscription’ in Spain’ story has over 1000 shares on FB… clearly, my people need me and my kind. Ok, No, 1: I’ve seen dogs with paws in plaster with better Irish script… [!!] No.2 Term ‘Galltacht’ only attested from 14thC onwards, v. infrequently (and should be ‘Galldachd’ or ‘Gàidhealtachd’… No.3 Earliest use of ‘Gaedhealtacht’ is from late 15thC, ie a century later than the church… No.4 If people bothered to check out orig website, one can detect a distinct & dangerous odure of people playing around ethnicity/race.’ That plate of pimientos looking better and better…

31 July 2014: MR writes: ‘I have taken a look at the original article. The inscription appears to be one of three placed vertically on the easternmost buttress of the Church of St James, Betanzos. These are described, from top to bottom, as a “Knight Templar’s cross” (sic), a yardstick and scissors and a ‘tree of life’ (sic). The ‘inscription’ is almost immediately below the yardstick with scissors. I do not understand why the cross would be described as a “Knight Templar Cross;” the order was suppressed c 1307 and dissolved in 1312. Apparently the church was built later in the XIV century. (http://www.betanzos.net/cgi-bin/Betanzos.pl?Z&Cliente=Betanzos&Ses=14072534913&Idm=es&OPC=TUR&RefM=3&RefOP=64&RefOP1=&RefOP3=26&DPL=&menu=ING&NOM=cultura_ingles2_2.htm&lin=cultura_ingles2_2.htm ) To me the cross is clearly the Consecration Cross at the easternmost point of the structure (that there necessarily be 12 crosses is a post Tridentine requirement) and the yardstick and scissors (sheers) a symbol for the Taylor’s Guild who apparently adopted the church in the C15th. (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Betanzos). The ‘stick and sheers’ and ‘tree of life’ (might this be a conventionalized palm or lilly) carvings are incised much less carefully than the cross which suggests they and the inscription are not a part of the original decorative scheme but a later and less formal addition. There seems to be no necessary reason to consider the inscription contemporary with the building, or with the other two incised decorations, and is it not more likely to be in an informal variety of the local script, with non standard diacritic or contraction marks, often used for both formal documents and inscriptions, and in the regional Galician-Portuguese ( Old Portuguese or Old Galician) rather than Gaelic? ( for images of three examples of this formal script, one in stone, at different times see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Galician_language) Enjoy the pimientos!’ Thanks Michael!

30 Sep 2015: Seamus writes ‘I have nothing to add to the claim of it being true or not but in your article you said:

‘an ghaltacht’ sounds modern. Gaeltacht is, in fact, the Irish state’s term for Gaelic-speaking areas in the west of the country. The first occurrence in the Oxford English Dictionary dates to 1926. Of course, the word might date back earlier in Irish literary history, where the OED rarely goes. I’d like to see that evidence though… (BTW gaeltacht is often translated as Irish-speaking area and the profs seem to understand it as such. There is no linguistic reference though in pure etymological terms: it is ‘Gaeldom’, i.e. it is ultimately ethnic. And, for the record, no fourteenth-century carver would have chosen language over race.) [see comments of Vox Hiberionacum below on the suspect form, the word as given seems wrong]

gaeltacht is also the name ‘irish speaking area’s use to refer to themselves, not a modern thing in irish. It is also not confined to ireland, scotish gaelic area’s also refer to their area as the gaeltacht. In english the gaelige speaking area of the north west of scotland was once called the highlands. The geographic and linguistic areas no longer match so no longer have the same meaning but they once did. The terms irish people and scottish people have clear definitions to them today but once upon a time the term gael was interchangable between gaelige speakers in ireland and in scotland. Some times modern concepts don’t fit easy even on familiar cultures in the past. At the time of this incription the 14th century, there was irish monks all over europe. Ireland and scotland had a strong monastic tradition for a few hundred years at that point, have not heard of inscriptions in stone but irish manuscripts are common enough in europe around that time, maybe if a history of the church was found a link could be ruled out or established.

28 Mar 2016: LC writes in I think you should do more research with regards to Spanish Irish links.