The Somers Affair: A Pirate Fantasy and Three Nooses July 13, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Modern , trackbackThe Somers affair is a curious incident dating to 1843 in which three American sailors were executed/murdered (opinions differ) in surprising circumstances. There is a lot of scope for psychologising and motive fishing, but the best bet is that this was an adolescent game that got very, very badly out of hand.

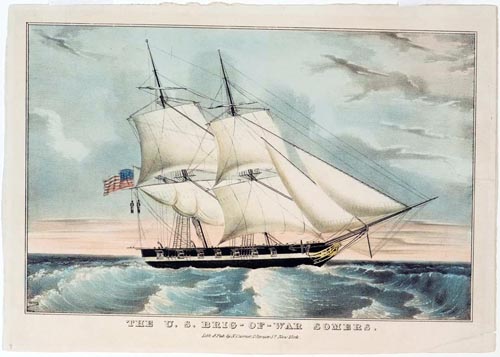

First, the bare outlines. The Somers was an American brig that had been launched in 1842. In 1843 it was captained by one Mackensie, a capable man but something of a martinet: he flogged his generally young charges with worrying frequency; though he was no sadist and his writing and the court cases that resulted from the killings show him to have been sensitive and intelligent. There were a hundred and twenty men on the vessel and among them was a nineteen year old officer named Philip Spencer.

Spencer was one of those troubled young men who will only have a good life if they get to twenty five having burnt out all the sulphur from their bodies: and how many manage that without prison or death intervening? He had already been kicked off two ships and had showed himself an addict of violence and alcohol. Mackensie may have provided an overstrict environment on the ship, but it was Spencer who was the vortex around which the chaotic events of the ship’s voyage span.

Spencer had been, there can be no question, thinking about a mutiny. That word ‘thinking’ is crucial because what has never been properly established is whether the boy was fantasising or whether he was actively planning for murder. Perhaps there is a middle ground: this was a fantasy that in conversation with others risked becoming reality. Maybe Spencer did not recognise the perils of his actions. If you fantasise about killing a neighbour, say, it is one thing: it is quite another to begin to share your fantasy with other members of your family, particularly if you have seniority and influence; or if family members are unstable. Spencer was dangerously charismatic.

Spencer’s plan was as follows: gather a number of trusted mutineers; fake a fight that would leave to the seizing of the arms chest; the commander would be immediately killed and likewise his trusted officers; the canons would then be trained on the deck and the rank and file would be brought onto deck, there he would choose some and have the others, particularly the young, made ‘to walk the plank’; they would begin to pirate other ships; men on captured ships were to be killed, the captured ship scuttled and any women were to be used as sex slaves before, also, being thrown into the sea…. Spencer had made the mistake of writing out a list of crew members, partially in Greek letters, stating who would be loyal and who would have to be encouraged and who would be disposed of: this list was discovered. He also drew pirate ships and showed crew members asking them what they thought of that.

This gruesome detail of the sex slaves and the plank walking gives maybe the truest indication of what was happening here. Spencer was dreaming unpleasant late adolescent pirate dreams while awake. It reminded this blogger of some of the absurd plans of the Columbine School killers, stealing aeroplanes and the like. But, of course, just because said plans were absurd it does not mean that these elements were not dangerous; that the dreamers were incapable of waking. The ship’s commander, on being first told of the mutiny, commented that Spencer had been joking; when Spencer was accused he made the same claim.

News of the mutiny leaked out and Spencer and several associates among the common seamen were arrested. Again had this been all then they would have been take back to the United States: perhaps two weeks away at this date. Then there would have been a proper court martial. The problem was that the Captain and his officers decided that there was a great deal of hostility from the crew and they came to believe that a rescue attempt was going to be made and the miscreants freed. This could only mean that the mutiny would, in fact, take place. At this remove it is impossible to establish facts, but it has been suggested that the senior offices had become paranoid: though this may be because the whole mutiny seems so absurd to a modern reader. Mackensie and his officers decided, in any case, 1 December, that the only way to guarantee security was to immediately kill the ring-leaders, Spencer and two of the rank and file, petty officer Samuel Cromwell and seaman Elisha Small. This was not a court-martial and so it seems inappropriate to use the word ‘execution’: it was, at best, necessary summary justice.

The three men were hung. Spencer tried to save the two others, claiming they were innocent. He also admitted his guilt though asked if the Captain had not exaggerated the danger: this contrasts with Cromwell whose last words were to claim his innocence. The captain, then, prepared Spencer for a Christian death with readings from the catechism: the strange cooperation between accused and executioner has been noted before on these pages. When Spencer owned to the captain that he feared for his mother, the Captain argued that his death now was a blessing as had the mutiny succeeded he would have carried out far worse crimes! Spencer demanded that Small forgive him, something that Small refused to do until the Captain interceded on Spencer’s behalf. One of the most interesting points of this case and one we’ve deliberately left to the end is that Spencer’s father was the Secretary of War for the United States! And the furious father would pursue Mackensie through the civil courts: a court martial found, by a split vote, Mackensie to be innocent; the man’s reputation was ruined though.

Other summary executions at sea: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com (I’ve found none)

13 Jul 2014: MR writes in with this and most importantly an amazing picture. Look for the hanging bodies… ‘Links to the two primary sources on the affair, which include the notes of the mutineers, ship’s deck logs etc.: Proceedings of the court of inquiry appointed to inquire into the intended mutiny on board the United States brig of war Somers, on the high seas : held on board the United States ship North Carolina lying at the Navy Yard, New-York : with a full account of the execution of Spencer, Cromwell and Small, on board said vessel https://archive.org/details/proceedingscour00navygoog Proceedings of the naval court martial in the case of Alexander Slidell Mackenzie: a commander in the navy of the United States, &c., including the charges and specifications of charges, preferred against him by the Secretary of the Navy : to which is annexed, an elaborate review, by James Fennimore [sic] Cooper New York: Henry G. Langley, 1844. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofnav00mackrich A review of the matter by a modern specialist legal historian David Howe Essay on the Legal Aspects of SomersAffair and Bibliography Naval Historical Centre, 2003 http://www.history.navy.mil/wars/somers.htm It is thought by some that this is the literary antecedent of Melville’s Billy Bud. Melville’s maternal cousin, Guert Gansevort (1812 -1868 later a Commander during both Mexican and American Civil War) was serving as First Lieutenant on the Sommers at the time of the mutiny and was the only commissioned line officer on board, besides Commander Mackenzie. See: Dolin, Kieran (1994). “Sanctioned irregularities: martial law in Billy Budd, Sailor”. Law Text Culture (Wollongong, Australia: University of Wollongong)1.1: 129–137. Delbanco, Andrew (2005). Melville: His World and Work. New York: Knopf. p.298. The subject clearly gripped the popular imagination sufficiently for Nathaniel Currier, later a partner in the celebrated firm of Currier & Ives, to publish a lithographic images of the brig underway with bodies hanging.

Lisa L. writes ‘Just wanted to add a postscript to your summary of Philip Spencer and the Somers “mutiny.” In 1848, Edgar Allan Poe wrote to a regular correspondent of his named George W. Eveleth that he claimed to know the identity of the man responsible for the death of Mary Rogers (aka Poe’s “Marie Roget.”) He did not give the man’s name in the letter, only that he was a “naval officer.” (Poe added that Rogers was not actually murdered, but died as the result of an abortion.) Poe also hinted that the officer had escaped punishment due to his influential relatives.’ Many years later, a Poe scholar named William Kurtz Wimsatt did a little detective work and concluded that Poe’s “naval officer” was Philip Spencer. We have no actual proof that Spencer was truly involved with Rogers, but it’s still, I think, an interesting example of unexpected links between seemingly unrelated historical events.