Fiume under D’Annunzio: An Incubator of Evil April 17, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackback***Dedicated to Ray G***

Everyone has dreamed of walking through Kublai Khan’s ice palaces or straying into the outer reaches of Dante’s paradise (after St Bernard has spoken) or, for those with a rural bent, strolling through the wood of Keats’ nightingale. But one early twentieth-century community spent the best part of eighteen months in these rarefied places, where the ‘old antithesis of life and dream has finally been overcome’ and where ‘the new forms of life are not only conceived but are fulfilled’ and it proved to be singularly unpleasant for almost all involved.

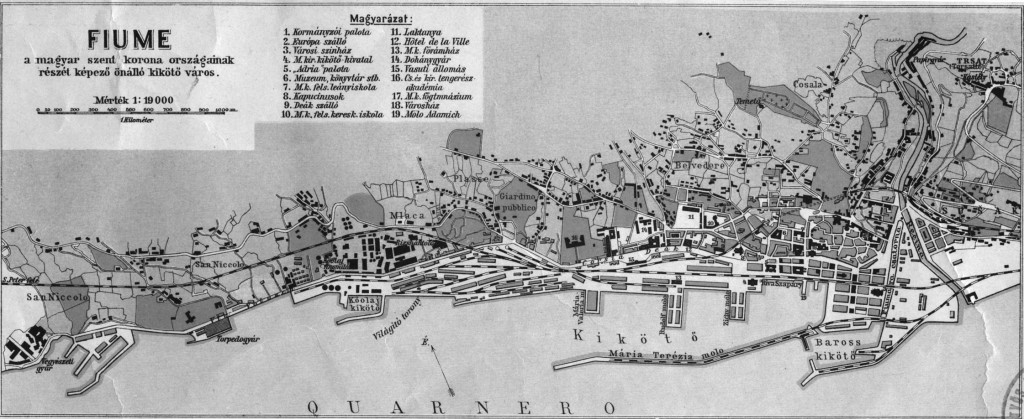

We refer to Fiume, a town on the coast of Dalmatia that had been, up until 1918 part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and which had showed no sign of or, indeed, desire to become an earthly paradise. It was though one of the ‘lost cities’, the cities dreamed about by Italian patriots as part of a perfected Italy: cities lying behind the frontiers but cities that would fall within the completed patria when God saw fit. Its population, talking now strictly of the city, was just over 50% Italian-speaking, the surrounding countryside was, instead, overwhelmingly Slav. But even the Fiumian Italians were of mixed descent. For example, the five heroes who began the movement for an Italian Fiume had the rather unitalian names of Mario Petris (which passes muster), but then Giuseppe de Meichsner, Giovanni Stiglich, Attilio Prodam and Govanni Matcovich.

So far so normal: depressing twentieth-century ethnic politics with the promise of a pogrom. But this was about to change. 11 September 1919 Italian poet and regular loon Gabriele D’Annunzio (pictured above) put himself at the head of a small militia and marched on Fiume. He and his nationalist followers had become increasingly impatient with the refusal of the other Allies (Britain, France and particularly the US) to accept that the Dalmatian coast should be Italian. (For any Italian nationalists reading this post, note that Fiume had never been in the Treaty of London, so there!) As a Nietzschean hero wannabe GdA decided to will-to-power through the problem. Given that thousands of soldiers were blocking the way the international community, meanwhile, relaxed: GdA could be brushed off. The problem was though that these soldiers were Italian and rather than block they flocked to the ranks of the poet and pushed on into the town with him. A red-faced Italy refused the gift of Fiume: acceptance would have meant the breakdown of relations with their erstwhile Allies. So Gabrielle d’Annunzio simply took over and became the duce of this small city in what is today Croatia.

If this had been all then we would had a historical curiosity. A passport-to-pimlico situation in the Adriatic, a bit of high comedy – let’s write a constitution, let’s set up a customs union…. – and then everyone would have kissed, made up and gone home. But GdA was a high eccentric who surrounded himself with high eccentrics. It is not that the inmates had taken over the asylum, it was so much worse: the inmates had dressed up in military uniforms, had walked out of the asylum gates and had occupied the city hall, claiming to be mayor, police chief and judge. And what is incredible is that, at least at first, no one seems to have noticed.

The ‘liberators’ were, certainly, greeted by ecstatic Italian-speaking crowds (the Croatian speakers sensibly stayed indoors). In elections later that month D’Annunzio’s candidates in a civic election would get 70% of the vote. But by December the numbers of those supporting his position had fallen to perhaps 20% in a ballot: we don’t know the exact number because D’Annunzio suspended the vote after irregularities; the irregularities being that he was losing.

What had happened in those two months? Essentially the local population had recognized their liberators for what they were. The Fiumians wanted to be part of Italy and in the words of one anti-D’Annunzian leaflet they wanted ‘freedom, peace and work’. They did not want to be part of a petri-dish in which D’Annunzio played around with his dreams of a new society. Yet the truth is that by December 1918 the Fiumians had ceased to matter. It was occupiers that had come to the forefront, the shadow warriors brought down by D’Annunzio from the borderlands. The Fiumians themselves were reduced to bit actors, lego bricks in D’Annunzio’s games: such as the occasion that they were ordered out into the surrounding fields to form the words ‘Italy or Death’ in giant letters, visible from the sky. (I’ve failed to track down any photos, perhaps no planes turned up?)

It is enough to look in the snapshots of the occupation of Fiume to understand that something is not right. The Italian soldiers came from different regiments and different backgrounds. But even after months in new units they failed to conform to a single mode of dress. They wore different styles of ties and altered their badges to suit their particular tastes: they are the precursors, in that sense, of WW2 partisans or, more darkly, of the dreadful Einsatzgruppen. They grew their hair long and wonderfully shaggy: or some, in imitation of D’Annunzio, shaved their heads entirely in the testa di ferro style. The modern skinhead was born in Fiume and with the often horrific bullying of the local Slav population skinhead politics finds its origin in Fiume too.

Soldiers, including D’Annunzio’s ‘man of action’ and enthusiastic nudist, the mad, bad and often sad (he was frequently depressed) Guido Keller did not just rebel in terms of style of dress: Guido is pictured below in a characteristic pose. They fought against the idea of hierarchy itself. Soldiers needed no rank greater than captain and the guardians of Fiume were to become perfect killers with knives in their teeth and grenades in their hands. They would be Homeric warriors ready to smash the old world and clean its wounds with their sanctifying violence. They were to be able, D’Annunzio insisted, to fight, to climb trees and to imitate animals. It’s not exactly the Fantastic Four, is it?

If this sounds like so much nonsense, then so it probably is. The Homeric hero was an anachronism against Roman legions, never mind against machine guns. But D’Annunzio and his men were fascinated by the idea of violence as a social antisceptic. There had been a lot of this waffle among the British, German and French middle classes before the war and, indeed, in the first month of the war: ‘as swimmers into cleanness leaping’. But the experiences of trench warfare had cured most participants. However, D’Annunzio’s men had fought a war, many with extraordinary bravery, and yet still saw violence as sanctifying and blood-shed as life-giving. D’Annunzio, for example, was given a bayonet by the women of Fiume and told solemnly that it was ‘to carve the word victory in the living flesh of your enemies’. Martyrs, meanwhile, were the seeds not of Christianity but of Gabrielle’s nightmarish new world order.

Morality, at least conventional post-war morality, was spat upon. This began with sex: local girls were recruited into love leagues and even homosexuality was welcomed among the soldiers, ‘as in the time of Pericles’ (D’Annunzio). As in modern Italy the cemetery was a place of privacy at night and it was there that ‘courting couples’ met and loved. D’Annunzio didn’t care for the cemetery but he still indulged in the most fantastic, acrobatic sex. One of his descriptions is of a foursome with three compliant women. Another description comes from a long-time resident of D’Annunzio’s Fiume, a one time friend of the poet and later an enemy.

There was a cellar, all decked out with white bear fur. There, amid the smoke of the incense, were committed unspeakable orgies, interspersed with satanic libations. Neither were artificial paradises excluded. Cocaine snowed down in the cenacolo and you sucked steaming blood from human skulls.

Where was Crowley in 1919?

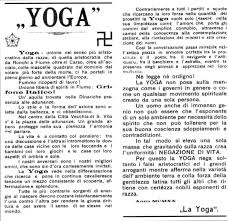

These excesses soon became mixed with other strands of alternative living. YOGA, an orientalist newspaper with a mystical bent was published in the city with a ‘life-giving’ swastika on the cover. It wanted to borrow a caste system from the Hindus but it wanted to separate humans out not according to their genetic descent but rather according to their spiritual potential: the eugenics of karma, let’s call it. The Fiumeans were presumably drones, the soldiers, well, soldiers and D’Annunzio and a few others the charismatic queens. (Thinking of D’Annunzio’s sometimes limp-wristed ways that is quite a good way of putting it…) Many of the YOGA club specialized in the red lotus: they became ecstatics, confirming themselves in extreme experiences of the senses, sex chief among them. Others were brown lotuses, tree-hugging and at times, you have the sense, ready to rip the tree from the ground to bring it down on the head of the enemy. All talked constantly of freedom, but only the exceptional would ever enjoy that freedom.

Then, politics crept slowly in. D’Annunzio combined, with a rare genius, the very worst of every political system available at this date: and in 1919 there were some pretty ghastly ideas sloshing around. His instincts were for a mystic nationalism, replacing Christianity with his virile and atrocious paganism. But he had also shown a long-standing interest in socialism as well. As a member of the Italian parliament he had even briefly joined the socialist party, before he realized that he would be expected to follow orders. Now at Fiume he combined his patriotic ravings with some of the most unpleasant left-wing politics imaginable: D’Annunzio put out feelers to the newly born Soviet Union to get Lenin’s support. The one thing that these two new politics agreed upon was the joyous necessity of violence in sweeping away the old world.

Others had been making similar alliances in the years before. Not least a sometimes collaborator (and editor) of D’Annunzio, Benito Mussolini (the two are pictured together above). There is a strong case to be made that the terrifying combination of left and right authoritarianism that led to Dachau was established in Fiume. In fact, one of D’Annunzio’s Fiume alumni would die at that notorious camp: nasty, wretched but essentially poetic justice. Mussolini, meanwhile, billed D’Annunzio as the John the Baptist of fascism, an epithet that worked for the messiah from Predappio, who three years later would take over the country and annex Fiume.

D’Annunzio’s finest hour politically was the writing and publication of the Charter of Carnaro, the constitution of Fiume. Here he handed over the task of composition to Alceste De Ambris, an extreme and violent leftist: who introduced corporatism and ‘collective sovereignty’ (the poison that would kill that great American innovation of ‘self determination’). D’Annunzio then hammed up the prose, wrote himself into the picture and changed the passages on music (!), religion and architecture. For D’Annunzio it was all a parlour game and his enjoyment was that of a precocious child with felt-tip pens and a big blank sheet of paper. He got, for example, to design the the flag of the Regency of Carnaro with its motto ‘who stands against us?’ (Quis Contra Nos)

Certainly, D’Annunzio enjoyed imposing his own order. The Arditi, the most fearsome of the Italian and Fiume warriors, were described as the ‘the dark seraphim of another apocalypse’. And one Jesuit resident describes how these seraphim worked ‘adjustments’ at night: punishing or killing those who disagreed with their Commander. In January 200 socialists were expelled from D’Annunzio’s Fiume and the Futurists were also driven out. Guido Keller – nudist, vegetarian and general psycho, described above as ‘mad, bad and sad’ – tried to set up a Committee of Public Safety, with no apparent sense of irony. It was less dangerous to live in Fiume than in the newly born Soviet Union. You were more likely to get roughed up than actually murdered. But the impatience with dissent is something that would grow through the 1920s and spread its wings monstrously in the 1930s. Almost everything bad in the 1900s hatched in D’Annunzio’s Fiume: the jewel of the Carnaro proved a seed bed for the century’s evil.

Owed this post to several books chief among them: Mimmo Franzinelli and Paolo Cavassini Fiume: L’Ultima Impresa di D’Annunzio (2009) and Lucy Hughes-Hallett, The Pike (2013). More on fiume: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

30 April 2015: JP writes in ‘just wanted to let you know that the pictures of gabriele d’annunzio showing his muscles published is a fake, a hoax. it comes from here http://nonciclopedia.wikia.com/wiki/File:D%27Annunzio_Superdotato.jpg

Thanks, JP but what a ‘true’ fake!