Migrating Birds and the Edge of the World April 3, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Medieval, Prehistoric , trackbackYear in year out birds follow migratory routes from north to south and from south to north. These travelling birds have long intrigued humans who have looked amazed as waves upon waves of birds fly to destinations unknown. These birds have entered human legend: the storks going to Africa to fight the pygmies, the wild hunt as Canadian geese get raucous on a cold winter’s night… But today I found myself thinking: ‘is it possible that early human communities made geographical deductions on the basis of migrating birds?’ I’ve focused in what follows on the north Atlantic but there may be other applications: if so I would love to hear more, drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

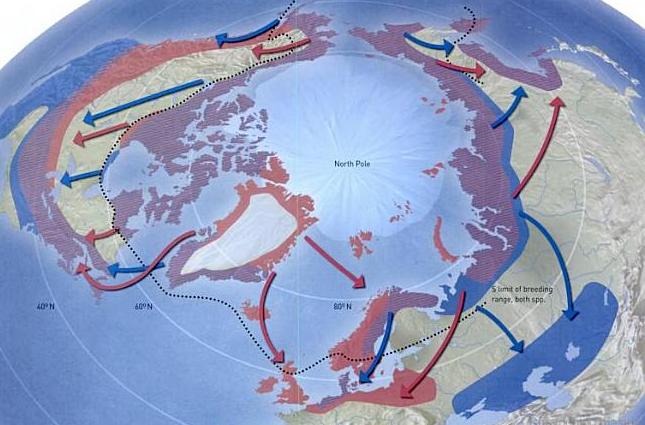

If you are in northern Scotland and you see birds coming from the north (perhaps the extraordinary Arctic Tern making its impossible journey to Antarctica) then you say ok that bird is coming from Orkney or from Shetland and you fall back asleep. But what if you are in Shetland or Iceland before Greenland has been placed on the map? What if you live in the western settlement in Greenland and see birds flying out from behind you towards the west and the open sea? What if you live in the west of Ireland when flocks of unusual birds come in off the Atlantic? You sit up in bed, you scratch your head. ‘Where do these come from?’ you ask yourself. Our ancestors in these peripheral places might have dealt with the problem is several ways. First, they might have played the birds-live-in-the-sea card, something that was particularly later associated with hirundines and that survived as late as the nineteenth century as an idea. Second, they might have shook their head, turned over and have snoozed some more. Third, they might have looked west/north/ etc and said ‘something must be out there’.

Even if they had deduced land to the west/north etc it doesn’t mean that the Galway man or the Icelandic woman would have necessarily been foolish enough to go and actually look for this land. But at least in northern Europe the migration of birds does seem to be a possible prompt if not for exploration then for deduced knowledge. From this area (north-west and northern Europe) I’ve not turned up any legends about migratory birds or, indeed, any archaeological remains that point in that general direction. But it is something that we know happened and something that would have been difficult to square with the mental map of individuals living on the edge of the world, or at least our understanding of that map.

24 April 2014: JTM writes in: A couple of interesting facts about migrating birds for you here. I remember reading a book some time ago about a white stork turning up in Germany with an African arrow (or spear?) stuck in it. A tiny bit of googling led me to this wikipedia page. Clearly, storks with implements stuck in them turned up regularly enough to be given the name ‘Pfeilstorch’. I also recall reading a book some years ago which recounted a story about a young educated gentleman talking about how hirundines were now known to migrate, and dismissing the old legend about them emerging from bodies of water. His gardener disbelieved him, and said he saw a house martin emerge from a local lake very recently. The young gentleman went to view the bird, and discovered it was actually a storm petrel – a mainly pelagic species that must have been blown inland by a storm (and just about forgivable to confuse with a house martin). Its close associations with water had clearly fooled the gardener! I wish I could remember where I read this, but it escapes me. The only other fact I can remember is that it took place in Norfolk. A third thing, which isn’t really a fact, is about Barnacle geese. Over the years I have read a very strange mixture of information about why they are called ‘barnacle’ geese. I remember being told that barnacle geese were named thusly because it was thought that they grew and emerged from goose barnacles. Several online dictionaries refute this, and state that barnacle geese were called this long before the term ‘barnacle’ came to refer to the sessile crustacean. I’ve also read that ‘barnacle’ has no clear etymology, but also that ‘barnacle’ might be derived from ‘hibernia’ – i.e. the ‘Irish Goose’, which seems a touch tenuous. I’ve also heard that the Gaelic word for both the goose and the crustacean is the same, which seems to predate the association in English, but I can’t remember the reference off the top of my head, I’m afraid. Thanks, JTM!