Blood at El-Halia June 13, 2013

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackCivil war is always terrible. But the Anglo-Saxon world has experienced, at least in modern times, relatively mild versions. The English Civil War was admittedly the most traumatic event on British soil in the last seven hundred years, but, with shameful exceptions from Scotland and Ireland, civilians were not usually put to the sword. Likewise the American CW, though a bloody and unpleasant affair did not see that many deaths off the battlefield save in certain hellish prisoner of war camps. (Perhaps the stark geographical separation of the sides in these two wars helped? drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com) Other countries have been less lucky and there bloodshed has become generalized and vengeful. The village of El-Halia (aka El-Hallia) in Algeria is a reminder of just how horribly and how quickly everything can go wrong. In a few days this well-adjusted Algerian settlement went from one where communal relations between the locals and French settlers were good, to one where the most appalling bestiality operated.

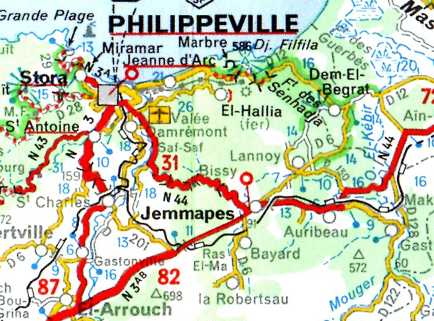

First, the vital statistics. In 1955, before it was changed out of recognition, El-Halia had about two thousand Algerian inhabitants and 130 French settlers (the Pied Noirs). There was a mine in the village run by the French: Algeria was under the colonial control of France, of course. But relations were generally good between the two communities with overlapping social circles. There was certainly not that stark division that almost always characterized African and European communities to the south of the Sahara in the colonial period. However, by 1955, Algeria was a powder keg waiting to explode. The FLN (the National Liberation Front) was stepping up its attacks and the FLN commander in the Philipville area – a man incidentally celebrated as a hero in contemporary Algeria – had decided that not only would civilian targets be hit, but that they would be deliberately targeted. French intelligence had brought back news that there would be attacks in this part of Algeria and French paratroopers and soldiers had quietly been brought in to surprise the insurgents. However, it is a measure of how peaceful El-Halia was that the Pied Noirs there thought that, in the unlikely event that they were visited by the rebels, then the Algerians and French would fight the FLN off together.

Unfortunately for the local French community by 19 August, at the latest, all their Arab neighbours seemed to have known what was awaiting the colonials. Some of the Algerians left with their families rather than have anything to do with the bloodshed that was to come, but no one passed a message across community lines. By 20 August at 11.30 the pied noirs were winding down work at the mine for lunch and the FLN was ready. Four groups of FLN fighters, each a score strong, broke into the village and began the attack against the Europeans. Most of these fighters were outsiders but there is no question that the local population was implicated. Not only did the villagers keep their silence in the hours before the killings, they seemed to have passed intelligence on to the killers, they accompanied them to the Europeans’ houses and the survivors recalled the terrifying you-you ululations of the village’s women during the attack. Within four hours a third of the Pied Noir population of the town had been annihilated: just under forty individuals, ten of them children. Several more were left for dead. The following is a vivid description from one of those survivors. It combines details of day-to-day life in a sleepy Algerian village with the horrors that followed: sociologists are forever going on about the banality of evil, but for Beach the intimacy of violence is far more striking.

I [Marie-Jeanne Pusceddu] got married on the 13 August, 1955, we had a great party and all our friends were there, including C., an Arab taxi driver we knew well. With my husband, we went on our honeymoon. On 19 August 1955 [they day before the massacre] with my husband, Andre Brandy… I took the taxi from C. to return to El Halia. During the journey, C. says: ‘Tomorrow there will be a big party with a lot of meat.’ I replied: ‘What feast? There is no party?’. I thought he was joking.

The next day, the 20 August, all the men were at work at the mine except my husband. It was just noon, we were at dinner, when suddenly, the screeches, the chanting and the gunfire surprised us. At the same time, my sister Rose, the youngest Bernadette (three months) in her arms, came in distraught, followed by her children, Genevieve eight, Jean-Paul five, Nicole 14, Anne-Marie four. Her eldest Roger, 17, was at the mine with his father. With my mother, my brother Roland eight, my sister Suzanne ten, my other sister Olga, fourteen and my husband, we realized it was something serious. The screams were terrible. They shouted: ‘We want the men.’ I told my husband: ‘Quick, go hide in the laundry.’

We locked the house, but the fellaghas [FLN troops] broke the door down with an ax. To our amazement, it was C., the taxi driver, our ‘friend’ who had attended my wedding. I still remember this as if it were yesterday. He followed us to the bedroom, to the living room, then into the kitchen and we were trapped. C., with his shotgun, harangued us. He immediately shot my poor mother in the chest, she tried to protect my little brother Roland. She died on the spot with Roland in her arms, also severely injured. My sister Rose was killed with a shot in the back. She kept her baby against the wall, my younger sister Olga threw herself in hysterics on the gun he fired at close range, wounding her badly.

He taunted us with his rifle. Bravely and distraught, I told him: ‘Go on shoot. There’s only me!’. I took the shot in the hip, I did not even realize it and he’d gone. I had children and I hid them under the bed with me, but I was suffering too and I wanted to know if my husband was still alive. I went into the laundry room and hid myself behind the structure there with him. The fellaghas and the son of C., returned. They came towards us and heard a noise, but one of them said in Arabic: ‘This is nothing, it’s just birds.’ And we stayed, scared, confused, without moving until five o’clock in the afternoon.

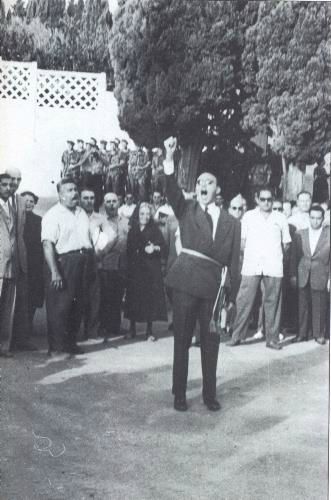

News had got through to Phillipeville by 2.00 pm, two and a half hours after the massacre began. A passing tourist bus had heard shots and a forest ranger, with extraordinary courage and luck, managed to get there to inform the authorities: note that there had also been killings in the larger town too; in fact, one of the most memorable photos from those terrible days shows a Phillipeville icecream stand covered in blood. The French proved anything but merciful as they clawed back control. Furious French Parachutists carried out, indeed, several massacres of their own killing the guilty and, all too often, the innocent: one Parachutist order in Phillipeville was to shoot any Arab out on the street on sight. Beach has stuck up above a photograph of the mayor of Phillipeville, at the funeral of the victims, singing the Marseilles. It is an extraordinary snap and gives some sense of the spirit of the Pied Noirs as they stared angrily into the abyss that was about to rise above them.

As to Algeria, once you take the cork out of the bottle, it is very difficult to jam that cork back in. It is tempting to see the Islamist murder of innocents in Algerian villages in the 1990s as the last echo of the machetes at El-Halia.