Hob and Documentation May 4, 2013

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval, Modern , trackbackHistorians with their infinite archives and supercilious (and usually ill-functioning) electronic databases need lessons in modesty. And here is a ‘lesson’ that Beach stumbled upon this morning. In 1861 the following appeared in a book on archaeology.

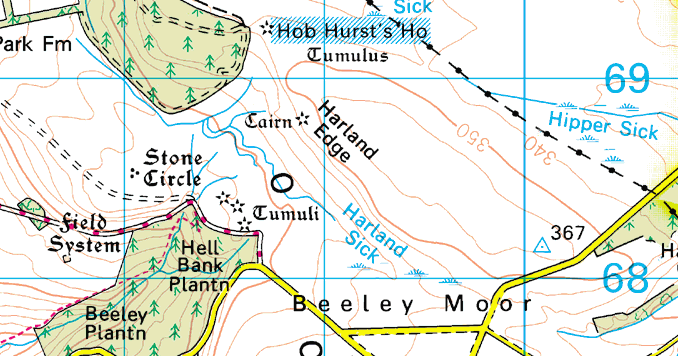

Mr. Bateman opened a circular tumulus on Baslow Moor [Derbyshire] called ‘Hob Hurst’s house’. It was a very interesting one. He says: ‘In the popular name given to the barrow we have an indirect testimony to its great antiquity, as Hob Hurst’s house signifies the abode of an unearthly or supernatural being, accustomed to haunt woods and other solitary places, respecting whom many traditions yet linger in remote villages.

So far there is nothing strange here. English moors are full of prehistoric structures that are named after mythical characters and the turbulent dead: in fact, some of our earliest reliable Arthurian material relates to places in the wild christened for this or that hero from the pre-Grail cycle.

But who actually is Hob Hurst? Well, the name hob appears often in relation to supernatural creatures. (Beach has distant memories of being jumped by some Hobgoblins in a Dungeon and Dragons game in a sweaty teenage dive, but he digresses). Strangely, no one has ever been able to settle on an etymology though there has been some scratchings tipped out of Welsh dictionaries: usually a sign of desperation among Anglo-Saxon scholars. Hurst, meanwhile, must be ‘wood’ (as in many northern dialects): we have then some imp with twigs for hair living on a moor with no trees for yards around… Oh the beautiful paradoxes of folklore! (A nineteenth-century scholar P.G.Scott tried to do away with poor old Hob on the basis of these paradoxes). But what really pleased Beach wasn’t Forest Hob, but his lack of historical success. The earliest and only other occurrence of HH is in one of the Pastons letters from 1489. First, William Paston quotes a ‘saucy’ rebel pronouncement:

To be knowyn in all the northe partes of England, to every lorde, knyght, esquyer, gentylman, and yeman that they schal be redy in ther defensable aray, in the est parte, on Tuysday next comyng, on Aldyrton More, and in the west parte on Gateley More, the same day, upon peyne of losyng of ther goodes and bodyes,for to geynstonde suche persons as is abowtward for to dystroy owre suffereyn Lorde the Kynge and the Comowns of Engelond, for suche unlawfull poyntes as Seynt Thomas of Cauntyrbery dyed for; and thys to be fulfylled and kept by every ylke comenere upon peyn of dethe.

This is fascinating stuff but for present purposes it is William’s comment on the pronouncement that deserves our attention.

And thys is in the name of Mayster Hobbe Hyrste, Robyn Godfelaws brodyr he is, as I trow.

So William says that the pronouncement was made in the name of one Hobbe Hyrste, brother of Robin Goodfellow. This is not quite as strange as it sounds because there is a medieval tradition of calling rebels fairies and also, more interestingly, of rebels referring to themselves as fairies (another post another day).

From the coming of the English to Britain, c. 500 to the Paston letter there are about 1000 years and Hob Hyrst does not appear once though men with pipes and women without husbands were probably telling story after story about him in that time. Now this is hardly surprising given just how little in terms of writing survives from that period and just how uninterested those who wrote documents were in folklore matters. However, from the Paston Letter to 1861, the best part of five hundred years, Hob only emerges in an obscure placename on a God forsaken moor. It is true that from 1489 to 1861 popular belief was declining, but the extraordinary number of published and written documents in that time would be enough to fill several modern English valleys. How is it possible that Hob did not emerge in that time somewhere? Quite simply whole sections of the experience of our ancestors, even in the early modern and modern period, slipped through the fingers of documenters. How easy it would have been for these two references to disappear too, particularly the Paston letter, which did not appear in the first, eighteenth century edition. Is it any consolation to poor old Hobbe that he now has a Wikipedia page? Perhaps.

Other examples of gaps in documentation: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

***

15 May 2013: April writes in: well, not actually you this time but this writer found herself saying to herself, “why isn’t the actual meaning of the sweet small word ‘hob’ not known by all?” Or, well, at least not known by you most specifically, being as you are rather informed and clever about such wise on the average. Where I was raised (another day, another missive) I cannot recall anyone ever wondering aloud or otherwise over the meaning or origin of the word hob. Why? you may ask. Well, herein lies the obviousness of it all — it being the why of anyone not knowing the singular syllabletimedness of hob’s true meaning and further evolutionary transformation within this ever changing vocabulary we loosely refer to as the English language, King’s, Queen’s or otherwise. But I digress. Hobbe / hob, depending less on your local dialect and more on the quite recent standardization of spelling — as I’m sure will ring loud bells in your memory — refers to an early (I do apologize for not knowing exactly how early) though still sometimes in usage, capelet of a kind with long wide ties which can be left loose to hang down the front of your tunic or kirtle, as the case may be, while warming the shoulders; or, more to the point, the splendidness of the hob’s design when put to its fullest use. That use being when the capelet is draped over the head with its widest part at ones midline, so to speak, and the long wide ties taken from left to right (and right to left, of course) and threaded through the provided slits — i.e. large button hole sorts of devises at about the then neck-line — on each opposite side of the hob, which, due to this very clever design, not only then covers the head and ears but can also, for very cold weather, be used to cover the lower face by the judicious crisscrossing of the ties into place. I do hope I am succeeding in providing a proper idea and mental image of the hob; because, when used in this manner rather than its shoulder covering capelet use, it’s rather easily seen how ‘hob’ — with only the single intermediate form of ‘hod’ — became the modern word ‘hood’. One can also see, quite easily it is hoped by this author, how Hobbe/Hob Hyrste/Hyrst and, for that matter, Robin Hood — more properly Robin Hod, it being during the time of this middling change — are names used for rascals — and in some minds down right gangsters (or in the modern vernacular gangstas) — since those of that sort of ilk tend to avoid exposure of the face during their acts of highwayman-shipping, even-the-scoring, or borrowing-from-othering (depending on ones point of view).I needn’t go into the explanation of hob-gobblins I’m sure. Enough said this author hopes.’ Thanks April!