Immortal Meals #12: The Feast to End all Feasts January 21, 2013

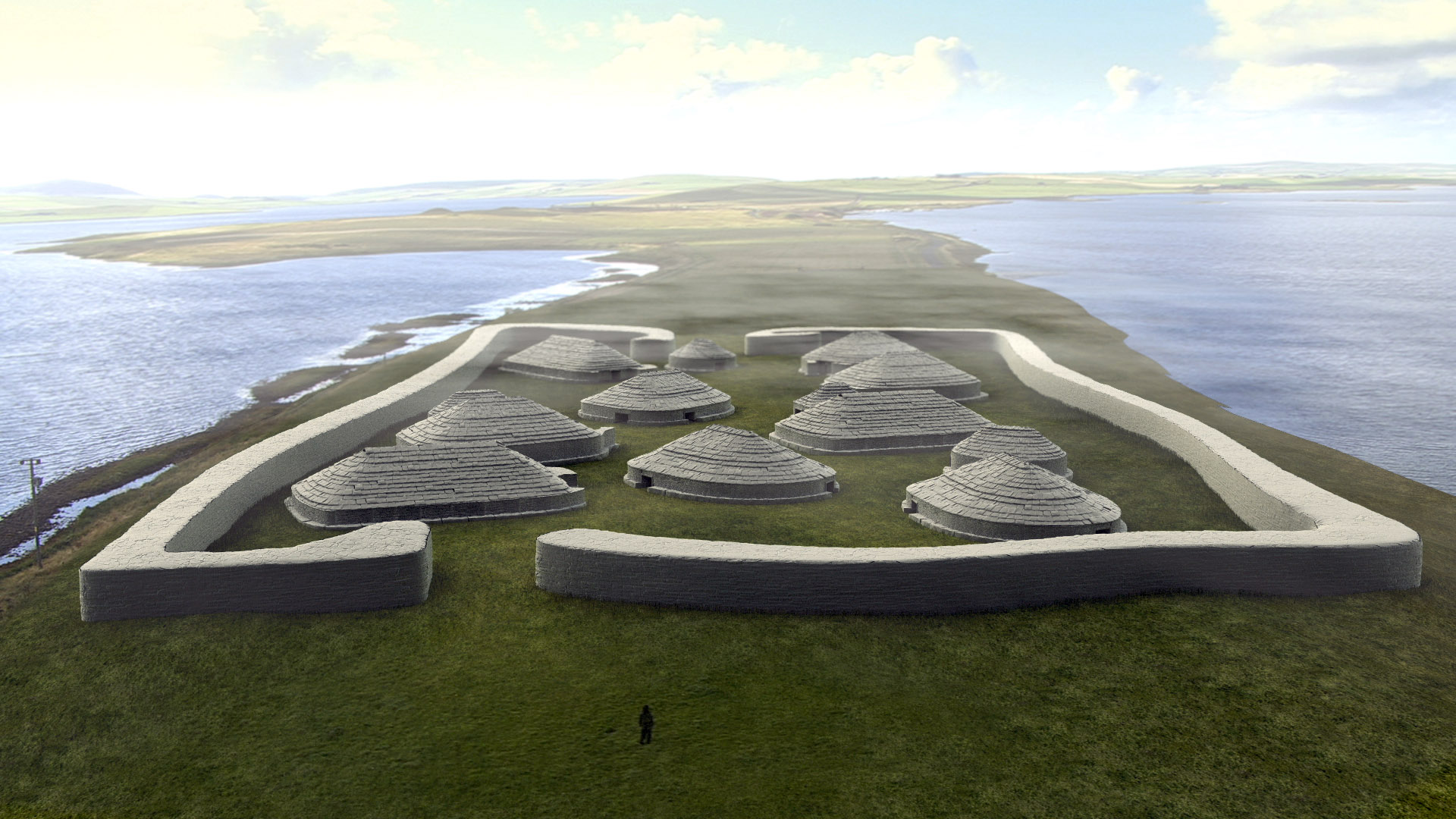

Author: Beach Combing | in : Prehistoric , trackbackThe Ness of Brodgar is one of the most impressive Neolithic sites in Britain and, indeed, in Europe. It includes a series of massive buildings that have been interpreted as mausolea or temples and that would have taken modern stone masons years to put together: without metal tools it must have taken the Neolithic Orcardians generations. The Ness stands between the nearby Ring of Brodgar and the Stone of Stenness – forefathers of Stonehenge – and there is a sense that this complex marked the omphalos of life in the islands. Perhaps it represented the omphalos for something even greater. In the last thirty years there has emerged a growing consensus that Orkney and the far north of Scotland were not an outpost of Neolithic life in Britain. Rather they were the centre and that innovations in pottery and circle building radiated out across the UK from there to such provincial dumps as the Thames Valley and the Salisbury Plain. But we have not come to the Ness to speculate about archaeological precedent. Rather we are here to celebrate a feast: yet another in our Immortal Meals series (see below for list).

The Ness was occupied c. 3500 BC and then was abandoned about a thousand years later: c. 2300 B.C at about the time that Stonehenge was being put together (probably). Before it was abandoned a huge quantity of cattle tibia or shin bones were dumped outside the largest building on the site: a building that has been immortalized by archaeological protocol as #10. There is talk of about six hundred different cattle in this tibia dump. Then in #10 an upturned cattle skull was placed in the middle of a ritual hearth towards the end of the occupation. Now six hundred cattle is a great deal: enough to make a Massai tribesman into a tribal leader. In Orkney in the third millennia BC this was an almost unimaginable number: in fact, the number is so large that this blogger at least has the suspicion that the counting has been badly reported. Are we talking about six hundred beasts or the still impressive one hundred and fifty beasts each with four tibia?

This picture taken from an extraordinary series of reconstructions of the Ness

Archaeologists love speculating about feasts and celebrations. It gives the trowel-belted ones a sense that they have a snap-shot of a moment of the past, rather than the blurry long exposures that are more usually their lot. Still in this case let’s concede the Orcadians a massive, unprecedented party: one that must have been like a kidney punch to the local economy whether there were one hunded and fifty or six hundred heads of cattle beaten towards the alters. More interesting still the tibia and the skull described above are from the final phase at the Ness. It has even been suggested that the feast would have been used to decommission the site. This was a kind of guys-we’re-changing-way-of-life-let’s-go-out-on-a-high-note soiree, one that archaeologists at the Ness have suggested very tentatively might be connected with the coming of the Bronze Age. It is a fascinating thought. Forget ‘party like it is 1999’ and what about ‘party like the way of life your great-grandparents x 29 generations have known is just coming to an end now pass that shin bone marrow will you’? Wild times in Orcades.

If we concede that there really was a feast – silly hats and fireworks have not yet turned up in the excavation – how did they get all the cattle there? Archaeologists have suggested, as hinted at above, that the Ness did not just serve ‘the parish’, but rather was used by the whole of Orkney and perhaps further afield as a pilgrimage point. If each clan brought two cows, the feast would have been more manageable, though God help anyone who had to get across the Pentland Firth with Daisy on the curragh. At the two nearby stone circles an archaeologist Colin Richards has suggested that different standing stones come, geologically speaking, from different parts of the islands. Each extended family would, he suggests, have had their own stone, which their ancestors had dragged there. In the case of the feast to end all feasts, each extended family would presumably have brought a bovine instead of a bottle.

Beach is always looking for other Immortal Meals: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

The Immortal Meals Series

1) Keats, Wordsworth and the Comptroller

2) Eating in a Victorian Dinosaur

4) Eating a French King’s Heart

7) Papal Orgies

9) The Discovery of Nero’s Rotating Dining Room

10) Love Feast in Renaissance Florence

***

22 Jan 2013: First up Stephen D on cow physiognomy: Pedantic points, though: I know things can be very odd up north and long ago, but I suspect that even late Neolithic Orkney cattle had only two tibia apiece, just like you and me. And the tibiae are the big bone in shank of beef: the shins have radii and ulnae, fused together (unlike in you and me). You can, of course, cook shank and shin much alike. MW has, instead, a point about cow transport: I’m not sure of the range of swimming cows, but in Scotland you don’t put the cow on the boat but rather make them swim behind: Next up is Ruth the Unstoppably Curious: I wonder if one even needed a curragh at that time to take Bessie and Daisy to the feast. If this speculative map is close to what the shorelines were back then, the site would overlook what appears to be a major strait and a rather large harbor. Maybe there’s hope for the silly hats… Seems to me it would be colder than today, though. Maybe not. The article says it started out as tundra, then turned into a very fertile plain. So there you have both colder AND warmer. I have long been fascinated with what the fishermen and marine archaeologists have been finding, especially lately. Thanks Stephen, MW and Ruth!

29 Jan 2013: More from Stephen: Colin Richards suggests that different stones in the great circles come from different parts of the islands. If he really did say “islands”, that implies that the neolithic Orcadians had boats capable of carrying great lumps of stone weighing a good few tons (the average Avebury stone is about 40 tons). If they could carry those between the islands – and it would need unusual magical powers to have the stones swimming behind the boats – there would have been no difficulty at all in moving cattle. Cattle of course are more lively than stones, and so perhaps a more troublesome cargo: but if they are being taken to a great feast, there is no need for them to be alive. Thanks Stephen!!