Witches, Confessions and the Truth November 25, 2012

Author: Beach Combing | in : Medieval, Modern , trackbackScholars of witchcraft in the burning years have an overwhelming problem. As rationalists they do not believe in the sabbat, devil sex or flying broomsticks. And yet, and yet… Women who were investigated often come up with the most extraordinary stories about the Satanic things that they have done. The problem for historians is why does this or that goodwife say that she has copulated with Satan, particularly if such a statement will lead to death? The answer or part of the answer is torture. These women were often (though not always) put through excruciating ordeals. In these situations, of course, they would say whatever was asked of them and if they were given leading questions then they would answer them satisfactorily. Still even that is not enough. Some of the details that witches come up with simply do not gel very well with the, my God, I-must-say-something-to-stop-the-pain theory. The details are, at times, extraordinary. One confession, for example, describes the way that four diabolical familiars fought over the witch’s teats: an image that must have come from pigs in the farmyard. It is difficult to imagine a prosecutor feeding this almost homely image to a witch. It is difficult to imagine a woman on the wrack screaming this out as the wrack is tightened a little more.

One explanation that is often used is that the ‘witch’ and her torturer form an unusual bond of dependence. In that bond the witch enters a ghastly, killing sado-masochistic game in which both individuals play off each other and in the end the witch is locked into the role that society has gifted her. There is a natural revulsion about this kind of theory and many scholars reject it out of hand, Beach has resisted its logic for years: and it is certainly not applicable in all cases. But perhaps it is has something to it. The following comes from an outstanding essay by Lyndal Roper.

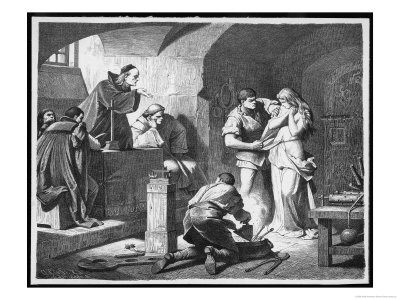

There is a further collusive dynamic at work in interrogation, that between witch and torturer. Torture was carried out by the town hangman, who would eventually be responsible for the convicted witch’s execution. Justice in the early modern period was not impersonal: the act of execution involved two individuals who, by the time of execution, were well acquainted with each other. Particularly in witch trials, torture and the long period of time it took for a conviction to be secured gave the executioner a unique knowledge of an individual’s capacity to withstand pain, and of their physiological and spiritual reactions to touch. In a society where nakedness was rare, he knew her body better than anyone else. He washed and shave the witch, searching all the surfaces of the body of the tell-tale diabolic marks – sometimes hidden ‘in her shame’, her genitals. He bound up her wounds after the torture. On the other hand, he was a dishonourable member of society, excluded from civic intercourse, and forced to intermarry among his own kind. His touch might pollute; yet his craft involved him in physically investigating a witch, a woman who if innocent was forbidden him. He advised on the mode of execution, assessing how much pain the witch might stand, a function he could potentially exploit to show mercy or practice cruelty. In consequence, a bond of intense personal dependence on the part of the witch on her persecutor might be established. Euphrosina Endriss was greatly agitated when a visiting executioner from nearby Memmingen inspected her. She pleaded that ‘this man should not execute her, she would rather that Hartman [her torturer] should execute her, for she knew him already’.

So do we have some very intense version of the Stockholm syndrome here? Certainly that last sentence is extraordinary. Or do we need to look elsewhere for explanations as to why witch’s confessed certain details: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com. The English witch trials, where torture was very rarely used, provide instances where the explanation above does not seem to work. Carlo Ginsburg the great Italian historian established, to his own satisfaction, that in some cases the women who were tortured and killed believed that they were taking part in some kind of religious system, which stood outside Christianity, at least as defined by the Reformation-era Church.

***

28 Nov 2012: The great Mike Dash writes: ‘Roper’s thesis has a certain plausibility, but there is another possibility I commend to your attention: that some testimony was the product of fantasy prone personalities. The FPP is a relatively recent proposal from the psychology faculty, still, I think, a theory that has yet to be rigorously tested for . But it would explain a lot, and not just about witches. The broad estimate is that about 4% of us are FPPs. I wrote briefly about all this here.’ Thanks Mike!